Zachary Armstrong

Published: January, 2016, Zachary Armstrong Paintings

MG: With two upcoming shows in New York you must have been very busy recently. Would they be two completely different shows?

ZA: Yes. I will show what I Call collaged paintings at Feuer Mesler. At Tilton I will show more abstract pieces.

MG: Is there a big difference in creating them?

ZA: It takes longer to make the collaged ones; they are harder and more stressful to paint. With the abstracts I have a starting point, which is a figure or a combination of figures, which I would transform and let dissolve in the course of making.

MG: Why are the collaged paintings so stressful to you?

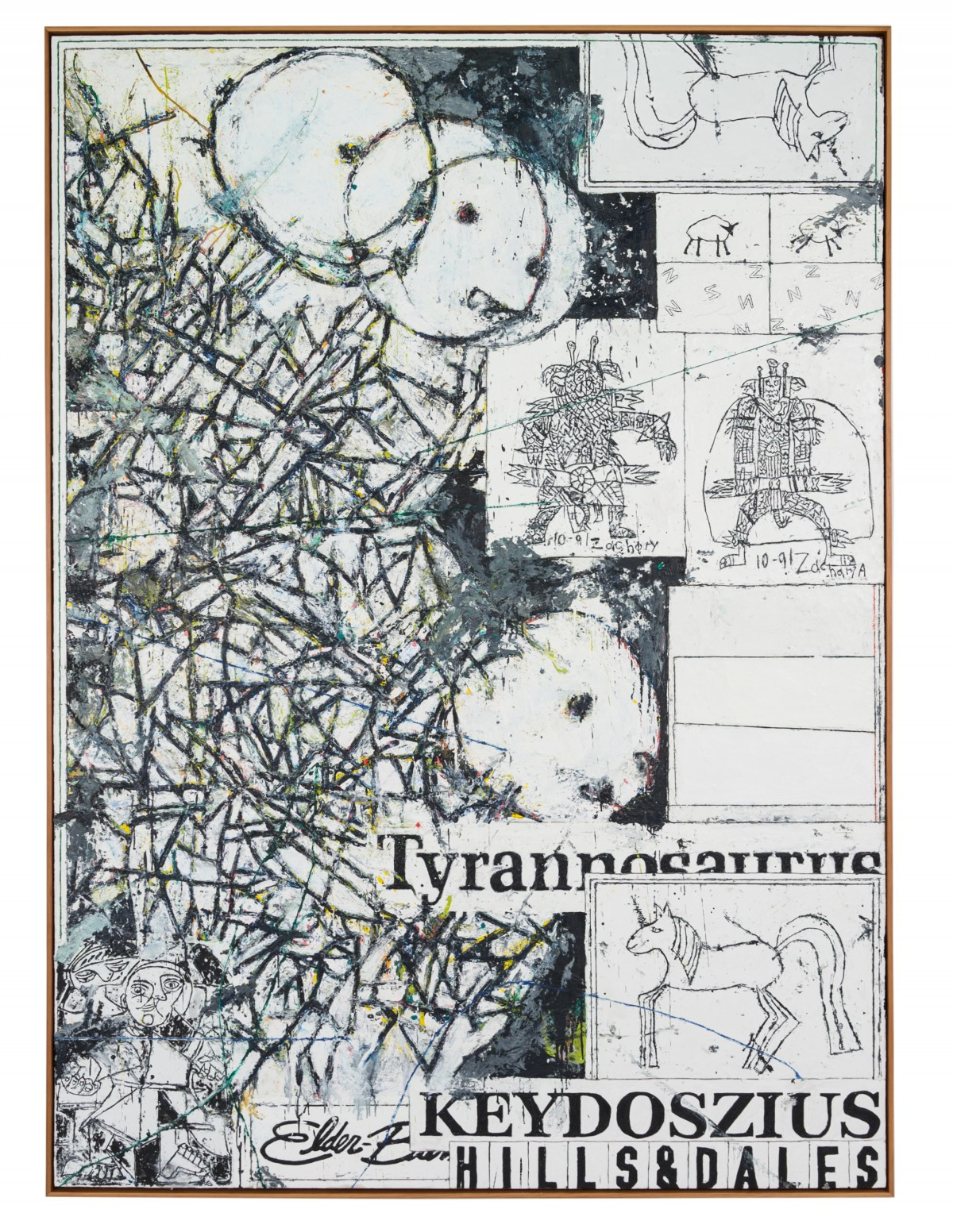

ZA: I combine them with my older paintings that I have kept just for myself. It is a process of recycling of old work from 10 years ago, like The Elder Beerman logo. I project my source materials into silk screens and use them as big blocks that I build up. Every painting you do, you get three more ideas; it is a non-stop learning process really. I always take notes.

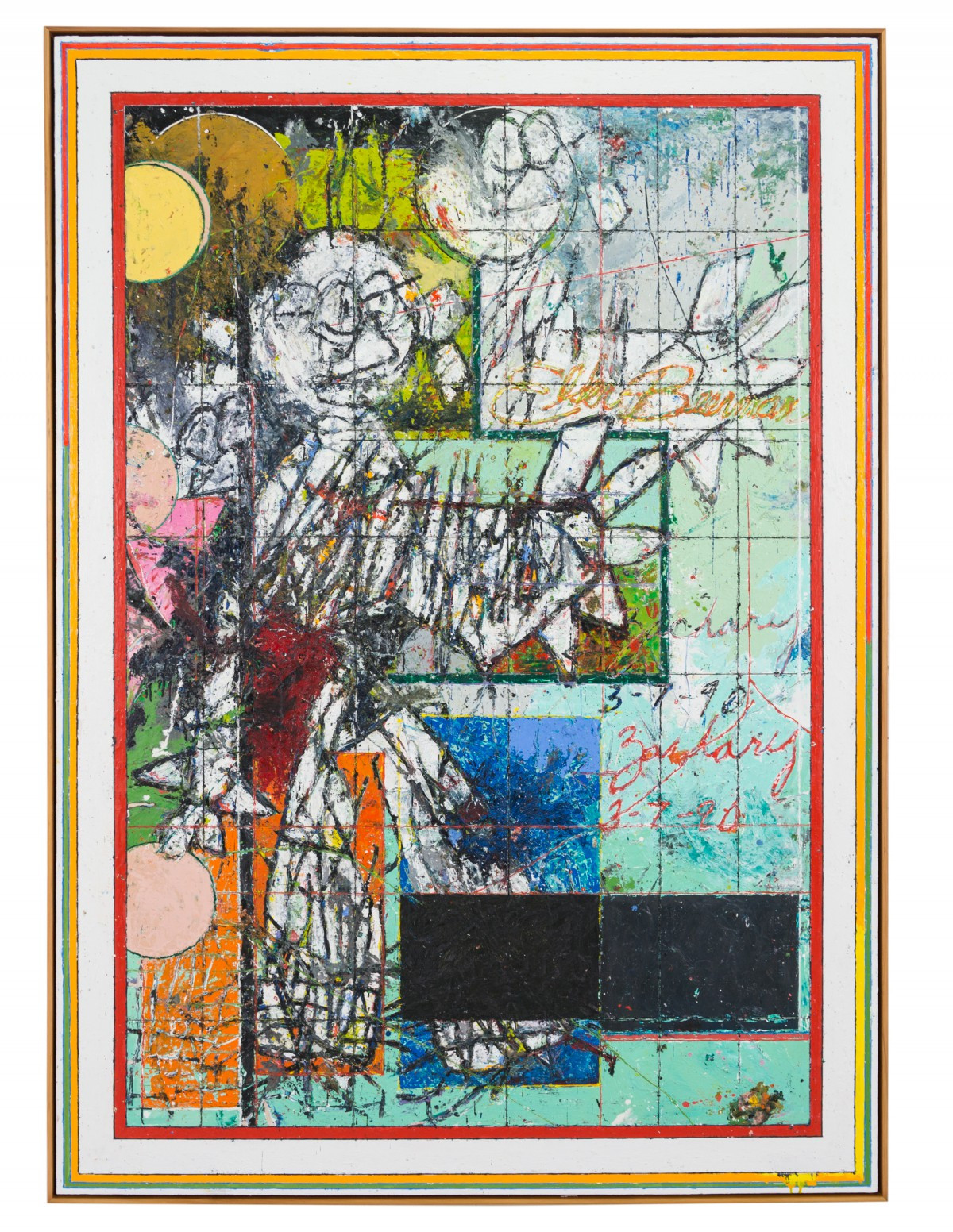

MG: Your new paintings look more dynamic than the previous works. The image has become crowded.

ZA: I’m trying to pack as much as I can in these paintings so there isn’t a single focal point. I don’t want to have any focus that forces a direct view but to the contrary: I want the image to be packed with details. I recently found myself asking questioning why I like Michael Williams’s paintings so much. They are not necessarily pretty. Then I realized that artists I admire most use a decentered composition, you don’t know how to look at them. Even in De Kooning’s figurative work, it’s hard for me to say if I’m looking at a woman or grouped details.

MG: It seems like you are consciously considering how to engage the viewer with your work.

ZA: Not necessarily. Working last year in my new studio I realized that everything I do feels more natural now. I have been painting in a way that I would do if nobody had ever seen the works. I almost wish I could make paintings that nobody would ever see. Right now with the shows coming so soon, I obviously think about the viewer and that’s makes the process of painting harder.

MG: What kind of pressure is it?

ZA: I’ve shown my early dinosaurs’ paintings in New York but I doubt many people there have seen any of my other work in person. I think New York is at the center of painting especially for my generation. I want my work to impress.

MG: What is so special about your paintings? From the composition point of view you just said that you have been following in the footsteps of De Koonig or Williams, not having the central composition. You use collage techniques; you manipulate the figuration by dissolving it into abstraction, which is also not new. So what is it that makes your painting exceptional?

ZA: Encaustic alone can make a painting a completely different thing. It is a difficult material that doesn’t react as anything else. The effects I can achieve with this medium are so broad. Especially with the new big blocks of collages and broken up abstracts I can’t think of anything like them. I call them collages but the process is more like building blocks. I want my paintings to look like they are more built than painted. Brush strokes aren’t super obvious. They look instead as if they were built with clay and not paint.

MG: How important in building the painting is the subject? Constant elements in your work are children imagery and personal motives.

ZA: I can’t help that. The new works are even more personal. Adding elements that wouldn’t likely attract attention and or communicate much meaning on their own makes a big difference to me. One big painting has my mother’s maiden name written on the bottom, which is Kaydoszius.

MG: Is this personal tour the lack of inspiration?

ZA: My work comes from my home, where I live, and is all very much related to me. Nobody would know what all of these elements signify unless you are very close to me. What I enjoy is that those elements become weird outside Ohio and my immediate environment and comfort zone.

MG: It is a coded work.

ZA: Yeah. Im comfortable with a viewer being unsure of what they are looking at.

MG: Childish signature is very present in your work. What kind of code is it?

ZA: It doesn’t represent anything except taste, preferences and myself. I’m not interested in making work as a critique on society or politics.

MG: So why are you painting?

ZA: I don’t know what else I would want to do. A part of me that likes making art is just being busy creating something. Some people told me that my paintings move them. I assume that most artists want to make art to let people feel deep emotions. I love how much is in them. If you see an amazing building you don’t necessarily feel anything spiritual or metaphysical but you are moved by awe or joy or by an undefined feeling because somebody could make something so massive and so complex that works. This is the way I want my paintings to look and act. I like art about making art.

MG: I can imagine that the process of painting could be wonderful. On the other hand, don’t you sometimes think that painting is actually a crazy activity?

ZA: It is very bizarre. I talked with my son about it too. But sitting at the desk all day long feels even more ridiculous – there are millions of seemingly ridiculous professions. But everyone has their thing. Painting is mine. There is something in art that plays to instincts. I think part of being human is wanting to touch, feel and make things that are bigger than one’s self. That seems timeless to me.

MG: How natural was it for you to start painting?

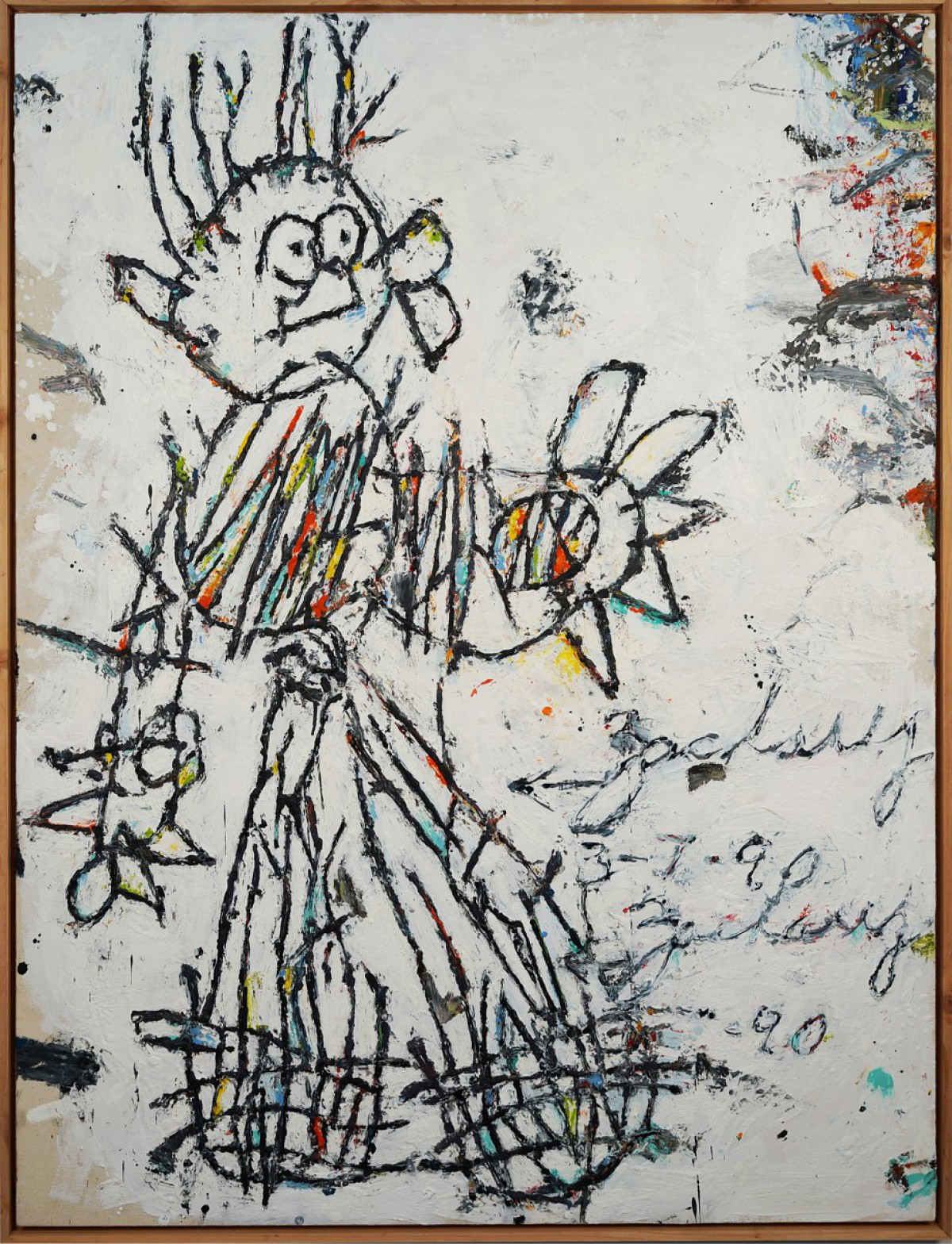

ZA: I’ve been thinking about this lately because the new works are much more detailed then before, so they somehow remember me of my drawings when I was a kid. I was already then obsessed with drawing. My dad was an art teacher and would draw with us, and my pictures had tons of detail. I don’t know why some people get obsessed with making things and others don’t. My son has no interest in drawing whatsoever, l; he couldn’t care less.

MG: Did you have the intention to study art?

ZA: I thought I would. In high school I was enrolled in a program that let me spend half the day studying art. I figured it out so there was only one hour of my school day that wasn’t related to art. But then I became a father while still at school and that changed everything.

MG: How old were you?

ZA: Just18.

MG: I assume this complicated your life a lot.

ZA: Of course. But I passed the tests I needed to, met all requirements and graduated a year early.

MG: In addition to fatherhood, what came immediately after school?

ZA: I worked like crazy. All of the sudden I needed to have a house and an ‘adult’ life. I knew how to build things so I worked construction jobs to support mu son and his mom. Sometimes I would draw or make little collages but I thought that making art full time was out of the question. It seemed impossible. I had to take care of my child, that’s the way the life was.

MG: You didn’t regret it?

ZA: I had a healthy child. I loved being a dad right away. Certain responsibilities had to come first.

MG: What made you change your mind?

ZA: I was in a pretty serious car accident. I was thrown from the car; my head hit the window first, I almost died. Everybody was hurt except my son. After that I realized – at that time I was 21 or 22 – how short life is. I didn’t want to die whereby the only thing I would have left behind were floors, walls and kitchens I had built in someone else’s house. It really scared me and I pretty much stopped working construction after that. I would work part-time when I had to; I was broke for years. I would work just to have money to pay the bills. Not long after that my son’s mom and I broke up and I began painting even more.

MG: So between 18 and 21 you hardly made any art and after the accident you took the risk and embarked on a new adventure: you had no money, no artistic education, you had to pay for your little son, you were broke most of your time and all you wanted to do was painting.

AZ: Exactly.

MG: Was this the moment when you started to use your own children drawings?

AZ: No, I was making all kind of different works. Some of them I’m now using as little elements in the new big paintings. I had the idea of children’s drawings for years, but I didn’t want to use acrylic. I knew they should be large scale but I didn’t know how to make them look the way I envisioned them. Once I started with encaustic six years ago I realized that was the medium that would be perfect for children’s drawings. Then I dug down deep in my parents’ cellar where they kept all the drawings, took the ones I really liked and I tried to make paintings out of them.

MG: Was this a breaking point in finding your own voice?

ZA: I think so. It has informed my path over the last few years.

MG: Is encaustic a difficult technique to manage?

ZA: At this point it is a second nature for me. It does take more tools and space: I have five or six hot plates set up the whole day, mixing the wax, making sure it melts at the right temperature. It reminds me of clay. It has a thick quality. I have always loved wax and even collected candles as a kid. I wasn’t ever interested in lighting them but I was sort of obsessed with the way they would all stick together. Maybe that has something to do with how much I love working with the encaustic.

MG: It must have been very exciting when you found your technique and material that you could define as your own.

ZA: It was good. I was getting lucky before it happened. I was still broke but things were starting to pick up – I could sell one of two paintings a month outside Ohio, get thousand or two thousand dollars, which I considered incredible, and survive. I was working on a show for this little gallery in Dalton when my girlfriend at that time bought a bunch of wax for me. That’s when I tired the encaustic. I knew pretty immediately that there was something special about those paintings.

MG: Did you keep any of those works for yourself?

ZA: Two of them.

MG: Do you try to keep works for yourself from lets say each phase of your career?

ZA: I try, but I probably should keep more. They take so long to make and they are my income.

MG: How long does it take you to make an exhibition?

ZA: It takes about 6 months to get a body of paintings needed for a show.

MG: Are you working on a few paintings all at the same time?

ZA: I like to work on one painting for the whole day, hang it up, leave it alone, do another one on the next day, then look at the first painting again. The longer you look the more you discover that can be changed.

MG: Lets go back to your shows in New York. As you said, it could be a tough place for an American artist, where it is probably very difficult to impress people. You are from a generation that is rich with painters. You also mentioned that you don’t like to explain your paintings into the current theoretical discourse. You are very intuitive and material oriented when speaking about your work. Are you not afraid that this attitude doesn’t help you to be noticed in the institutional world?

ZA: I don’t know. I hear some young artists layer on big deep meaning to their work. I feel like I can sometimes tell to which art school they went to by the way they talk about it. The artist I look up to most sound honest when they talk about their work. I doesn’t sound like it comes from anywhere else. My intuition and process is what I can talk about honestly.

MG: You are in the worst category of artists: male white hetero. Not really fashionable at this moment.

ZA (laughing): I can’t change that. Again, it’s be very dishonest for me to pretend Im not white, hetero, male – fashionable or not. I am me, and I make the work that only I can make.

MG: Do you relate your work to a bigger context?

ZA: I’m obsessed with art. I’m always trying to read what is going on in the world, what s being made and what is thought. Subconsciously I can’t avoid thinking about other artworks. Often while I’m making a painting I’ll find myself thinking about artists I admire and wondering to myself if the piece I’m working on would hold up in a group show along side their work.

MG: Do you feel yourself a part of a certain tradition?

ZA: Perhaps after 10 years it would come down to that. I’m pretty isolated in Ohio so it’s hard to feel part of a movement or community. And I don’t think it is up to me or to other artists to define it. This is the job of the art critic.

MG: During your exhibition in Berlin many viewers sought to put your work in the tradition of Jean Dubuffet, because of the materiality and the texture of your painting and the relation of childlike creativity. People wish to think in lines of continuity and references. It seems unavoidable.

ZA: I love Dubuffet; if anyone were to compare me to him, that’s a great compliment. But I feel like when I’m working I can’t give ‘my place’ much thought. It’s just not where my head is at.

MG: Do you consider this dynamic, packed painting style your new direction?

ZA: Yes. What is in my head are paintings tense with imagery and details. It gets busier every day. My dream would be to paint two paintings a year. Just packed with details.

MG: Do you think that if you would spend much time on each of them, the paining would become better?

ZA: I never rush the process. And I do feel like the longer I work on a painting, often the better it gets. Sometimes details matter that nobody would even notice; I’m redoing them just for me.

MG: In Berlin you were showing your works together with the British artist Rose Wylie. How did you like the confrontation with her, an artist who is extremely free in her way of painting?

ZA: The show was beautiful; it was a big honor to show along side her. The two different kinds of paintings being next to each other – I thought it worked better that I hoped for. I have always admired artists like who can paint so freely, who can make a beautiful picture by free movements of their hands. I take things that I like and reproduce them – there is not a real freedom except the freedom of choosing what I like.

MG: She works extremely economically, trying to do only necessary means to achieve the effect she wants. You like abundance.

ZA: Exactly. I wish I could do what she does. Before I saw the show in person I thought the juxtaposition of our work may be a bit odd – two forms of ‘childish paintings” in the same space; but I think worked well.

MG: A part of her economical approach was also driven by practical motives. If you don’t have money to make great painting with lots of paint you try to make it with minimal efforts.

ZA: I used to think a lot more economically than I do now. Now I can afford all the paint what I need. The first time I made encaustic painting I could afford two pounds of bees wax and paint without pigment. Those paintings were pretty black and white because I couldn’t afford anything else. That’s when I started using black for the initial outline. I never used artists’ canvas but instead I’ve always used drop cloth canvas.

MG: How does it feel now to be a successful young artist?

ZA: I honestly never thought it would ever happen. To say I want to be a successful artist feels about like saying you want to be successful actor, the chances are slim. I feel incredibly fortunate and am very grateful to everyone who has supported me and takes an interest in my paintings.

MG: Has your life changed a lot recently?

ZA: I have a bigger studio and I can afford all the material I want. The cost of living is pretty low in Ohio. No way that I would have a studio like this in New York. Living here really lets me just focus on work. There are virtually no distractions. A close friend from childhood now works for me stretching canvasses and making frames, which is really nice. I wake up every morning, take my son to school, and then work in my studio until I can’t do any more. I usually work 10 to 15 hours a day.

MG: You have no social life?

ZA: Not really. I leave the town about once a month, keep my social life there and when I’m back home I just work. That’s what I do. That’s all I’ve ever wanted to do.