Vera Lehndorff / Holger Trülzsch

Published: September, 2014, ZOO MAGAZINE #45

The artist duo Vera Lehndorff / Holger Trülzsch created a rich and compact oeuvre in the ’70s and ’80s. Before they met, Lehndorff had a career as Veruschka, the celebrated supermodel of the ’60s, declared by photographer Richard Avedon to be “the most beautiful woman in the world,” while Trülzsch explored the territory of art, music, and politics as one of the leading figures of the student movement in Munich in the ’60s.

Marta Gnyp: When did you start your cooperation?

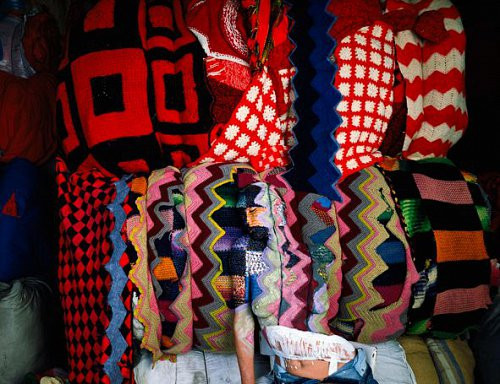

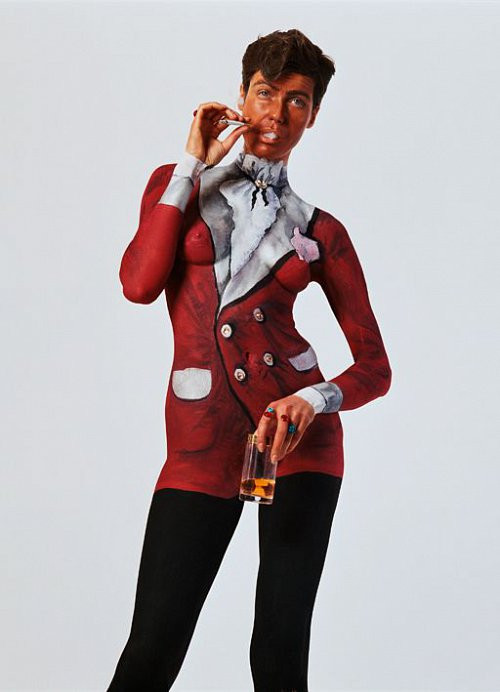

Holger Trülzsch: We started in the ’70s. One of our first works was the series Mimicry-Dress-Art that was an ironic critique of the es of the time. I painted dresses on Vera’s body, she did the hair and the facial expressions. We used the characters of the rock-and-roll stars like Mick Jagger or movie stars whom everybody knew. It was about all the icons whose gestures were quite fixed and recognizable to the big audience.

MG: What was your common interest in making this series?

HT: After I finished my study at the art academy in Munich, I studied human science and particularly the media theory. I knew nothing about the fashion world, not even Veruschka. I just knew this crazy model scene from Antonioni’ s Blow Up and her famous pot talk:” I thought you are in Paris…I am in Paris”. But then we met.

Vera was the insider of this world of celebrities.

Our goal was to achieve a critical irony towards the media workings.

MG: How did the idea about body painting come about?

H: Initially we didn’t intend to paint the body. We bought dresses and other things, which we thought we needed to create for example Jack Nicolson. We were faced with a problem though as we realized that by making the project using dresses and makeup only we can’t be more ridiculous than the people we’re imitating. Perhaps more funny, but then the danger is that you make just a primitive joke. Then we thought that painting the dresses on the skin might be stronger;

MG: How important for the project was the fact that Vera was an icon herself?

HT: This was the central point of the project: her being an icon and understanding how the media functions in creating personalities. The icon Veruschka is always shining through the imitated figures. This turned out to be something very strong so we caused scandals in the ’70s. But the media structure of the capitalist society, can easily and smoothly reintegrate everything, even a strong social critique. Instead of being rejected it became a success.

MG: Which you didn’t want?

HT: Well, it was great because it came as a surprise to us. For Vera the project was quite dangerous – she risked not being able to continue working.

Vera Lehndorff: I was already more or less out of the fashion world when we started the project. For me it meant something new: I was at that time enjoying making my diary, taking some Polaroids. I was discovering a new world for myself. I didn’t think any longer what the consequences would be in case I wanted to go back.

MG: How did the fashion industry react to your new ventures?

VL: People in the movies and fashion didn’t like what I did very much. They would say to me: “Veruschka, we prefer you beautiful.” At least what they thought as commercially beautiful. That was funny. People always think that you feel hurt if you’re not commercially successful. I never felt that way. I didn’t want it any more.

MG: It must have been quite a change to go into the art world.

VL: Yes, although it wasn’t so new because I came from art. I studied textile design and art at the technical college of Hamburg before I became a model, so you could say that I was on the way becoming possibly an artist. I had been still a very young woman so fashion was to me an attempt at finding a way to cope with the world. This crazy world of fashion became a possibility for me because I didn’t experience it as reality.

MG: You were in this unreal world for a quite a long time though?

VL: From 1962 till the ’80s, on and off. I was known in the fashion world in the ’60s, but I got famous to a wider audience through my role in Antonioni’s film Blow Up in 1967.

HT: The fashion world was completely different at that time: smaller and not so extremely focused on commercial success. Today that’s the only thing that counts.

MG: How did you two meet?

VL: End of 1969, in my mother’s house on the countryside in Bavaria. Holger was recording a disc together with Florian Fricke as the electronic music group POPOL VUH.

HT: I was quite a successful musician, painter and sculptor in Germany. As a dedicated leftist I was one of the leading figures of the student movement in Munich. In1968 the protest movement found its climax, collapsed and Vera came along.

MG: Were you each others’ destiny? Vera was fed up with fashion and you were fed up with the revolution.

VL: I came slowly back to art.

HT: The student movement didn’t understand how the media function. They were not able to cope with what was going on, they refused taking pictures or filming to document their actions with the exception of a few figures maybe like Cohn-Bendit in Paris and Fritz Teufel in Germany who developed very good strategies in the media. Teufel became very fast famous but he also misjudged the system. He accepted being put in jail for terrorist activities although he knew he was not guilty and he could prove it. He spent five years in jail without saying anything and only then did he present a document, which proved him innocent. He wanted to demonstrate how badly the capitalist system functions – but he made a mistake since our consumer society can consume anything, even an innocent guy in jail.

MG: So you were disappointed with the power of the revolution and its possibilities of social changes. Did art give you an opportunity to change anything?

HT: I wasn’t really disappointed, it just had an end. Through the Mimicry- Dress-Art we developed a different kind of critical analysis.

MG: Did you see artworks of Veruschka before you started your cooperation?

HT: I saw the film Stop Veruschka where I discovered some body paintings by her.

VL: It was called Stop Verouschka because the director of the film was my ex-boyfriend who was very upset that I had left him. I told him not to use the name Veruschka in the title because it was not my story. When we came to the premiere though, the sign Stop Veruschka was put everywhere on posters. That was when Holger saw my head painted under the running generic of the movie.

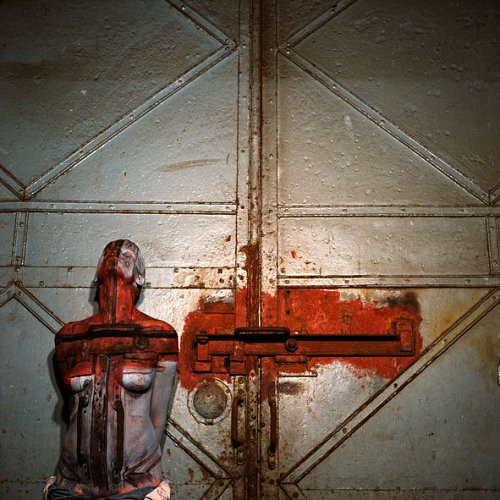

MG: Did you explore body painting often?

VL: Already after three years in fashion I started thinking of body painting but it was initially an animal painting, flower paintings in the face, or making my body look like a skeleton. In the 1960s you could do this in fashion magazines, but may be I became already slightly a bit unsatisfied with the fashion world.

MG: Why was it so urgent for you to leave the fashion world?

VL: When I came into fashion I had the idea that I could create something beyond the surface. This is why I engaged in body painting: it was a question of creating something new. I copied Picasso’s drawing style. But I didn’t have a clear concept until I met Holger.

MG: With whom you placed your desire to shape and transform the body into the context of social critique.

HT: As a painter, you are always partly a Pygmalion. Many painters mimic this kind of painting on the body, like Magritte. It was always this complexity of what can be treated as canvas and what is the real body. It’s rare that someone really painted on the body for the body’s sake. Among others Gilbert and George or Gunter Brus, did it about the same time as we did ; in the fashion magazines it existed already in the beginning of the sixties as a kind of make up.

MG: Gilbert and George have been working together but they consider themselves as one artist. What is your position in this regard, are you one artist together?

VL: We tried.

HT: For our first project we needed Vera’s name Veruschka because her fame as an icon was part of the project.

MG: Who coined the name Veruschka for you?

VL: I thought that it sounded very Russian. When I started to work as a model in the USA I was the only one who came there from close to the Iron Curtain. I was a sensation. They would ask me: “Are you from Russia?” The place where I was born, Königsberg, is a part of Russia now. The name worked perfectly well in the fashion world.

MG: Would you agree that art and fashion are becoming closer?

VL: I’d say that they’ve been very close for a long time.

MG: What makes art art and fashion fashion in your opinion?

HT: Art has nothing to do with fashion and fashion has nothing to do with art. Fashion design is intended to shape a product that then becomes consumable not necessarily functional.

VL: Well, there are artists who use design and fashion to make art.

HT: This is different I think. Fashion and design are just more or less useful in many ways, even as an unusable object, it is just the opposite of art.

VL: Sometimes fashion photographers today can make very artistic series, even better what artists are doing. In commercials you can see more interesting images than in art.

HT: This is a problem, but not the point. Commercial images are based on seduction in order to create an unnecessary desire for consumers. Art is about complex languish systems and not just about pretty images.

MG: Were you never accused of doing fashion photography and not art?

VL: No. We were accused of being speculative.

HT: I speculated on her fame and she speculated on me as an artist to become an artist. But this is nonsense. There were also other models who became artists, this happened.

VL: Niki de Saint Phalle was a model. The wife of Irving Penn, Lisa Fonssagrives, was a very good artist. He really loved her work.

MG: How was your mimic series received?

VL: People didn’t understand what this was all about. We were addressing the icons of the time but we used them because they were so typical. This month some pictures from this series will be shown in Warsaw for the first time in an art context.

HT: People were wondering what does it mean: “Everybody wants to be Mick Jagger, even Mick Jagger”.

MG: Did you continue working with this series despite this initial disaffection?

HT: We also attempted to undermine the function of mediatic representation of icons, stars in the world of fame and glamour. Once we became relatively successful we got an offer from Playboy to make body paint series. We made a blue Marilyn Monroe with blue menstrual blood. PlayBoy cut off the puddle of blue color running from her legs.

VL: Then for the women’s magazine Emma we made a cover with the founder of the magazine Stern in Germany, Nannen, who had an obsession with naked women. We made a very nasty face of a middle class man with a Playboy in his hand. I looked really horrible: like a horny, dirty old man but with my tits very present. He didn’t have hair so I combed my hair in one direction like some men with only a few hair do to cover their heads. I looked disgusting. The magazine Emma liked it very much.

MG: How were you formed artistically at this time and before? Did you visit galleries or exhibitions?

VL: Of course not me. I was obviously interested in art as I studied textile design and painting for three years in Hamburg. At the time I was very much engaged in looking at art but then along came fashion… After meeting Holger we started doing our thing. We had a first big exhibition in Hamburg in the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in 1978.We had 25.000 visitors.

MG: Did you operate through galleries or did you often meet other artists?

VL: Not at the beginning – the network of the galleries started later, in the ’80s.

HT: In 1985 our commercial success started: we had two galleries in New York, we got articles in Art in America, Artforum Time magazine, Die Zeit, and many others. Our openings had been crowded with artists. Andy Warhol didn’t miss one, Schnabel, Clementi, Mark di Suvero, David Salle, Mapplethorpe, Basquiat, Longo, Cindy Sherman, John Kessler and many others.

VL: Very good people cared about us. The art essayist Susan Sontag got enthusiastic when she saw our work and wrote about it, as did the writers Gary Indiana, Robert Hughes, Collins and Milazzo, Severo Sarduy, and other writers and critics. Many artists attended our openings. We lived in New York.

HT: I had a great time in the 70ties in SoHo which was like a little village, just beside little Italy. Matta-Clarks‘s Food restaurant had been just one block further from Robert Hughes loft which I split with him. Gordon was cooking and frying some of his photos in his kitchen.

MG: Why did you stop then?

HT: The crash in the world economy arrived in the late 80ties in the art world. Many galleries closed down as well as our gallery.

VL: You can’t do body painting all your life. We were both moving into another direction. I was living in New York, Holger did big installations in Paris. I didn’t have time.

MG: Were you developing your own work at that time?

VL: On and off. I’m not like Holger who is a pure artist – he works every day in his studio. I was doing performance films, ash projects, which I’m also doing now. I’ve finally found the right place to do it – it’s not easy working with ashes.

HT: You exhibited your ash works at PS1 / MOMA. Myself I did important installations works in France as well as Museum exhibitions at the Centre Pompidou, and other venues.

VL: It wasn’t the real ash project yet. I simply wanted to make photos and to disappear into the street, becoming a part of it as if I were homeless. The series The Burning City looked like it was just post 9/11 but it was made long before. The museum showed it in October 2001. I also made a video piece for them.

MG: How do you work now?

VL: I don’t produce a lot, although I’m always doing something. It takes time for me to develop a project. I actually don’t talk about my art. There’s nothing to talk about really since my works speak for themselves.

MG: Is your art about emotions?

VL: In life everything is about emotions. When you do a project, though, it’s this energy that keeps you going, not the emotions.

HT: Art is about searching for a language. The moment you believe in creating emotions you make kitsch or publicity.

VL: I think making art has something erotic. When I was young, I often felt this erotic attraction towards people. Now all of a sudden with art you realize that there is the same kind of attraction, which leads you to work. The excitement is very important, but sometimes very difficult to get. If it’s gone I don’t give a damn, I don’t want to do another picture. Holger probably has no problem with this because he can always work.

HT: It’s a technique. The moment you immerse yourself in a painting or an installation it creates itself, so you keep on going, like a writer who starts writing a book but doesn’t know in advance how things will develop. The books lead lives of their own. This is a matter of technique and passion. You never know when it’ll work. Like life – it’s a surprise.

MG: Holger, your case is clear: you are an artist. Vera, would you call yourself an artist?

VL: If you need only one label to describe who I am, then I would call myself an artist. I’m not a musician, I’m not a cook, I’m not a journalist, but I’m in the process of searching for something, which I’ll probably never find. Sometimes I hear comments like: “You left fashion to become an artist?” But this is not the case and this wouldn’t be possible. I was born like this. I remember as child I was already looking at colors and forms.

MG: Did you consider staying in fashion and exploring art through fashion? Wouldn’t it have been possible to explore fashion from the inside without leaving it?

VL: I did what I could do. I created a fashion line, for which I designed everything including the makeup and hair. There is a limit, though. At the time it was the right decision to leave.

HT: When we met, models where on the way to become commercialized objects.

VL: I never thought of being commercial or making money, which was stupid by the way, I used it for something else and there was an end to it. I’m still being asked to take part in fashion shows. I always say: “Don’t you see how old I am?”

MG: Why wouldn’t you like to do it now?

VL: For what? You do three days of hard work to fulfill somebody’s idea of how he sees you, because then you don’t have any ideas any longer. I said once and for all: it’s finished. I’ve done some crazy things in my life: I’ve performed as all kinds of animals in the streets, bums, Marilyn Monroe, even the president of the United States, what else I can do? I’m on another road – maybe when I’m 100.