To speculate or not to speculate

Published: May, 2014, DIE WELT AM SONNTAG

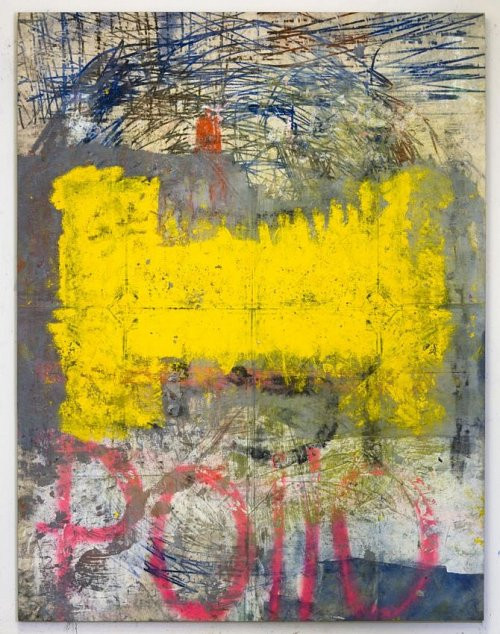

During the gallery weekend of 2013 the Berlin public became acquainted with the latest abstract paintings made by the British-Columbian artist Oscar Murillo (born 1986). Murillo, who graduated from the Royal College of Art in London in 2012, paints on unprimed canvasses, using materials such as oil, dirt and cement dye. He draws lines with a broom stick instead of a brush, and writes simple graffiti words that often denote types of food. Within only a few weeks, the art world came to associate the name Oscar Murillo primarily with the astonishing auction results that were gained by his works: at a Christie’s auction in London his painting Untitled from 2012, estimated 30-46.000 US$, ended up realising the price of US$ 391.475. The galleries that represented him at the time were selling similar work at prices between 30-40.000 US$, but as these works became highly sought-after, the galleries had nothing to sell. The more paintings by Murillo and other young artists we have seen in each and every auction of Christies, Sotheby’s and Phillips, the more the term flipper landed within the art world, hand in hand with the classic fear that art is now only about money. Also the results of the last auction week in New York showed stunning results: an abstract painting by the 25-years old Lucien Smith achieved 233.000 USD, a painting by David Ostrowski (1982) 281.000 USD, while a pastel cloudy abstraction by the 31-years old Alex Isreal hit the record of more then 1 million USD.

‘Flipping’ indicates the practice of acquiring assets only to quickly sell them for profit; a term originally used in real estate or stock trade. However, if we are to believe the media, today’s art world is full of flippers. They concentrate on the so-called wet art – so young that the paint is not dry yet- and often on abstraction. The good thing about flipping is that reports on gigantic profits attract even more people to the art world. With the ‘right’ Murillo you could have a 1000% value increase in one year. The bad thing, among others, is the danger of ruining fledgling artistic careers since flipping creates a quick artificial hype, which is likely to be followed by a long-lasting stagnation hangover for the artist.

So how come we suddenly entered the flipping era? Flippers didn’t appear out of nowhere; their emergence is a phenomenon that belongs to the contemporary art system, which has undergone substantial transformations since the end of the 20th century. The collectors of today, the flippers included, are a product of several artistic and social shifts that have challenged the existing approaches to art and collecting in general.

During the 1990’s the prototype of the artist became that of an attractive public figure, who has no real intention of threatening social conventions and who delivers visually attractive and conceptually entertaining works. In the tradition of Andy Warhol, artists like Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst continued the performance of their own personalities to the public, crossing the traditional boundaries between art, marketing and entertainment. Publicity and mass media have become an important part of the communication between the artist and his or her public. At the same time, the notion of the avant-garde – which implied a new beginning with a historical zero point, as well as the rethinking of existing conventions of art and society – started to disappear as the artistic ideal. Koons has played an essential role in directing the new conceptualisation of art and the artistic towards the intended pleasure of the audience. He compared his art with television; available for everyone to watch, and allowing people to become involved in their own way. Some viewers linger on the sensational level, others proceed to the more intellectual one, leading to the ever-increased abstraction of ideas. Koons’ purpose was not to bash collectors and the public, rather he wanted to include them in his artistic process. By doing so he created art that was autonomous and conceptual, yet popular and conceived according to commercial rules.

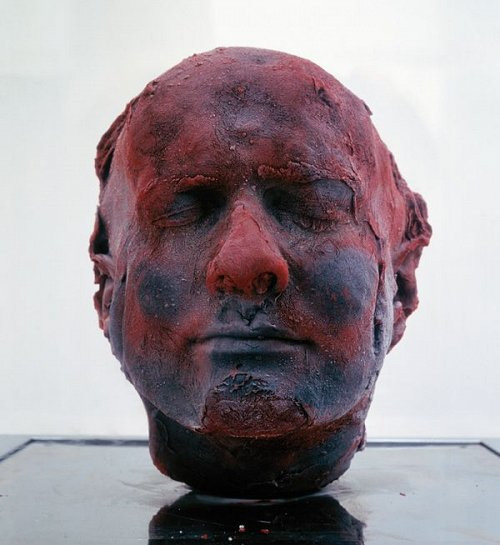

Another person to exemplify a certain aspect of the shift in artistic practice, is Damien Hirst. From the very beginning of his career, he took up the role of curator and dealer of his own works, as well as the works of colleagues. He organized the exhibition Freeze in the Dockland warehouses in London in 1988, and owing to the absence of interested galleries, he took care of the publicity in order to attract potential collectors. Young British Artists, as they were later named, were often looking for a “killer concept”, a spectacular invention that would be able to catch huge attention of the audience, as exemplified by Marc Quinn’s sculptures filled with his own blood.

As ingenious, creative ideas that were in a sense related to advertising strategies, became apparent within artistic practice, the validity of the leading critical theory and theories of French post-structuralism started to expire. Consequently, the lack of dominant ideologies allowed many different standpoints to co-exist. Furthermore, art has now expanded its territory to those practices that were previously considered to be different disciplines, such as fashion and design. The borders between high and low, mainstream and underground cultures have become all the more blurred, and the viewer has gradually been given more responsibility in the creation of the meaning of an artwork. In the past, nobody in the small art world seemed to care about the outside world, but by the end of the 20th century, artists consistently started to call the viewer the final interpreter of the work. In short, to the collectors that enter the art world in the new millennium, art has become an inviting aesthetic and social experience, which promises all kinds of enjoyment without requiring deep intellectual involvement.

Many of those new collectors have been formed by major corporate shifts that were taking place in the 1990s and that have had far-reaching consequences until today. According to the American sociologist Richard Sennett these shifts have resulted in ‘capitalism cutting edge’: managerial power has been exchanged for shareholder power, which is inclined toward wealth-increasing global investment. The banking system became international and as a result part of the banking commerce lost its connection to the national states. Instead of long-term strategies, investors started to focus on gaining short-term results, partly owing to the emergence of immediate communication on a global scale and the increasing speed of transactions. The new generation of collectors to enter the art field brought along the notions of global orientation, the employment of impatient capital aimed at amassing quick profit and the lack of long-term commitment.

Some of those new collectors ignore the two unwritten rules of good collecting, the first one of which states that a good collector never sells the works he or she once bought. This rule serves the primary art market and keeps intact the existing market structure that originates from the nineteenth century. The artist produces work, the gallery sells, the collector buys and the work is taken out of the art circulation. In this ideal situation the gallery can control the supply and distribution of the works and regulate the prices. Galleries reward collectors who do not succumb to the temptations of the market and never step back from a decision once taken, often by giving them a moral acknowledgement for supporting artists’ careers or more concrete, a first choice to buy or access to useful information.

The contrasting attitudes of an unwillingness to sell on the one hand versus the excitement of profit on the other, have been cultivated as characteristics that constitute the distinction between the long-term and new collectors. Many of today’s new collectors don’t necessarily intend to relate to the older elites nor do they copy their behaviour, as used to be the case in the past. Whereas long-term collectors stress their disinterest in art as an investment, and promote their deeper knowledge of art and responsibility for culture, the newcomers seem to consider a historically embedded connoisseurship negligible for being a successful collector. They declare good taste as being arbitrary and hold the opinion of peer collectors investors as being as valuable as those of critics. The authority of cultural elites is questioned and what makes this opposition even stronger is the financial superiority of newcomers with whom many long-term collectors cannot compete in the acquisition of expensive works.

The second unwritten rule of collecting claims that a good collector buys with his eyes and not with his ears, which means that a good collector doesn’t follow the rumours and trends of the market but uses his eyes to judge for himself. This demand addresses the fundamental ideology of collecting: the collector is given access to an unusual, individual understanding of an artwork only if he is authentic and open-minded enough to discover the quality and essential cultural values of the time (which apparently are not represented in the trends). At the same time this unwritten rule attempts to prevent buying trends, which can lead to the flipping or dumping of works, depending on the situation.

Flippers buy with their ears and resell the works to make money. They disturb the unwritten art market rules, traditional sets of moral values and the ideology of collecting. However, they are no outcasts; they are part of the same art system. They enjoy art and the art world, which to them has become understandable, quick and intellectually undemanding, although the enjoyment relates more to price increases then to emotional attachment to art works. Flippers often see themselves as passionate collectors but ones who quickly replace one passion by another. Absence of financial ‘suffering’ when buying art, the speed of the current market and relative indifference towards profound connoisseurship, makes that they lack long-term commitment for specific artists and art movements. The American artist Chuck Close told a story about a collector who was waiting for years to get Close’s work, which he promised to donate to a museum in Texas. The day after he received the work, he sold it. When the upset gallery owner asked him for an explanation he replied: ‘Well, I may be an art collector but I’m a businessman first. Anytime I can triple my money in one day I will do it.’

Flippers in particular tend to prefer young and abstract paintings, which they buy from galleries and re-sell in the secondary market shortly after. It’s not hard to explain this interest for everything young and painted. In general, young works are cheap, available and appropriate for speculation, since – inevitably – all expensive artists of today will have once started low-priced. As for the medium painting, it has traditionally been the easiest medium to sell at auction. The preference for abstraction however, requires a closer look.

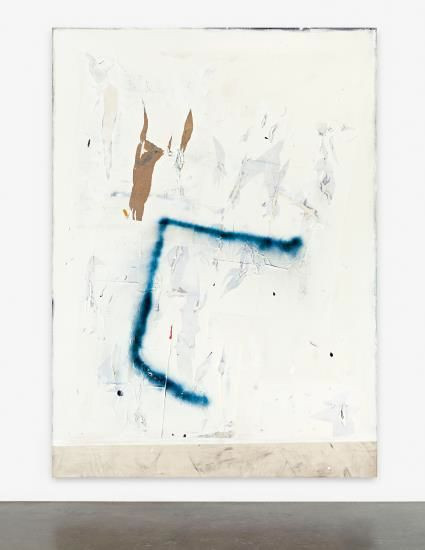

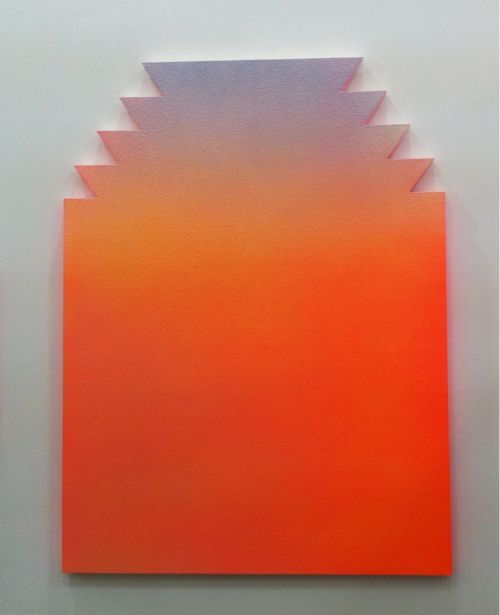

The variety of approaches in today’s abstraction is large, but for many artists urban popular culture is the source of material and inspiration. Lucian Smith sprays acrylic paint with fire extinguishers on unprimed canvasses and calls them Rain Paintings; Michael Manning makes works on tablets in Microsoft Stores; works by Israel Lund look like blown-up colour photocopies of paint surfaces, while Dan Colen paints with bird shit and chewing gum. Although these works play with the very elements of the medium painting, they don’t aim to strip the pictorial language to its elemental forms, as was often the case with modernism. Instead, today’s abstraction carries a narrative of production, whereby its resourcefulness – the killer idea – seems to be of crucial importance. This approach strongly contradicts the ideas of historical abstraction, such as Abstract Expressionism that hoped to elicit an aesthetic experience from the viewer. The statement that Mark Rothko made in the 1960s: “The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them” is miles away from the conceptual approach of contemporary urban artists who dislike the sublime character of the medium and instead root their paintings in various daily narratives.

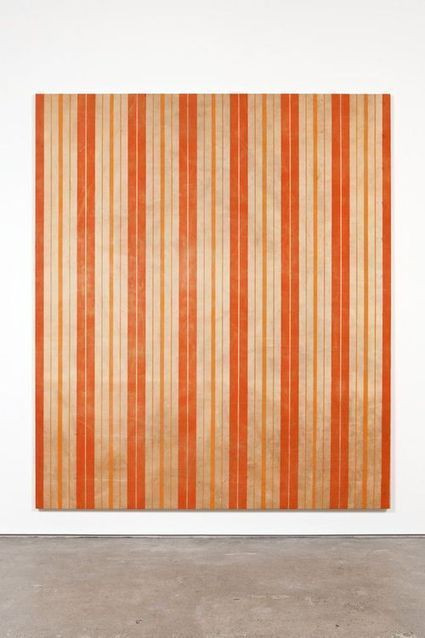

The work of the now popular Norwegian artist Frederik Vaerslev exemplifies how Urban Abstraction functions. He starts by painting an abstract geometrical construction of stripes, after which he exposes the canvas to unpredictable weather conditions. His idea is to let nature participate in the process of making the work and to allow randomness. Such a working procedure can be interpreted as conceptual, which distances the works from the territory of pure painting that might be considered old fashioned, while at the same time its visual appearance offers the possibility to relate it to important historical abstract painters like Barnet Newmann or Frank Stella. In this way Urban Abstraction seeks its connection to the art history without carrying the heavy theoretical burden. These works depend less on the pre-conceived ideological frames and can function in the art world without critical approval.

To collectors, these abstract works appear as formally attractive – some of them simply as beautiful – and at the same time as conceptually stimulating and playful. From the practical point of view the specific techniques applied by each particular artist allow these works to be made in a short period of time, while their recognisability makes them susceptible to branding. The branding quality of Urban Abstraction is of vital importance to the popularity of the works in the art market, as their formal repetitiveness simply enables a quick dealing. Thanks to the Internet and programs like Instagram, paintings can change hands without having been seen in real life. More and more collectors are getting used to acquire works on the basis of jpegs after having seen a work by a given artist just once. Branded products play with the heterogeneity principle of art, which are the perfect conditions for flippers to strike, as homogeneity is the basis requirement for tradable assets.

Flipping is a marginal phenomenon, but it signifies a potential shift of values and rules. It indicates that within the art system, including all participants, there is more and more room for hedge funds strategies that seek financial excitement and instant gratification in the first place.