The tormented soul of art between social revolt and speculation

Published: January, 2022, Domani

Apostles of democratization of art should be happy – contemporary art has become broadly accessible, popular, and easy to digest for big audiences. Everybody is an artist today – not in the Beuysian sense that we all possess a potential of artistic creativity – but more literally: legions of self-thought artists are enthusiastically promoting their work on Instagram to newly born collectors convinced of the judgment of their innocent eyes.

The international art market is on fire, like many other investment asset markets, by the way. Works by young artists that are yet to show any art historical or cultural relevance are being sold for hundreds of thousands or even millions of Euros – think about Flora Yukhnovich, Emily Mae Smith or Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe). At the same time, the hunger for trophies of art history’s big names seems unsatiable. New technical possibilities make market information instantly accessible and translate the available data into smart-looking rankings and reports. Don’t forget the NFTs, those strange creatures, certificates of authenticity incarnated, living their own life on a blockchain together with virtual cats, dogs and computer codes. Shortly, the globally expanding art world has become fast and furious, changing existing relationships between producers and consumers, while questioning long-believed narratives and authorities.

The book New Waves. Contemporary Art and The Issues Shaping its Tomorrow published by Skira is my attempt to understand what is going on and how to make sense of what is happening. Thanks to interviews with artists, curators, collectors and art market specialists the book gave me, and hopefully gives the readers, first-hand insights into those profound changes interwoven within fascinating personal stories.

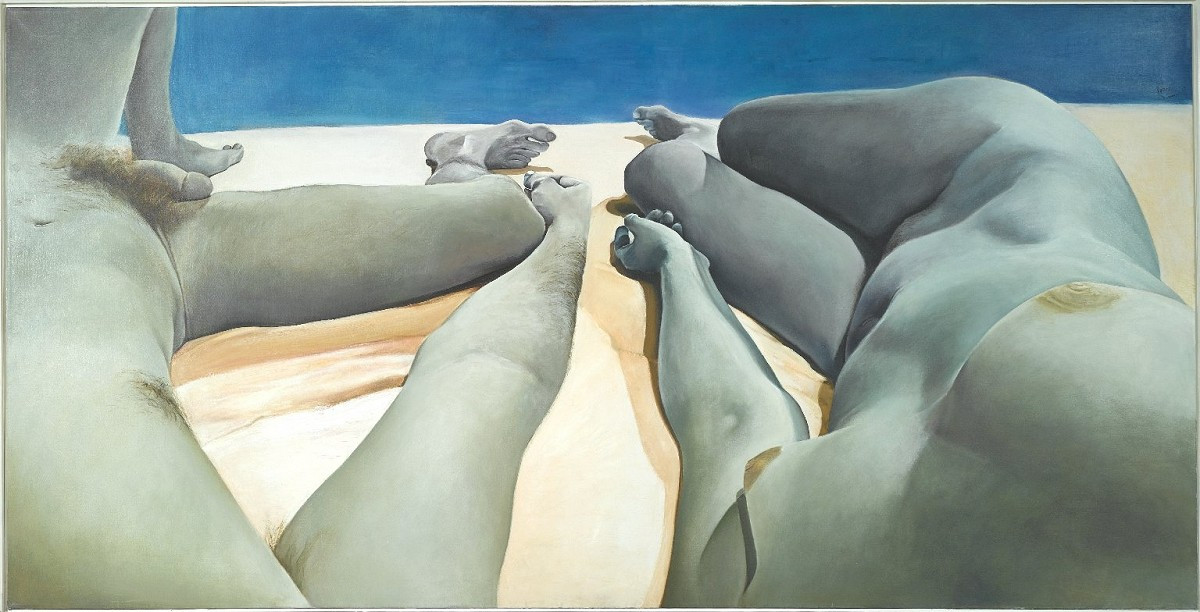

One of the most striking transformations that have deeply changed the art world is the process of rediscovery and revaluation of post-war artists who have been gaining their dues only recently after years of working without the proper acknowledgment from the art system. This applies mostly to female artists or artists of color who were lacking career possibilities because the art system refused them proper access. The Americans Joan Semmel and Stanley Whitney, the UK-artists Lubaina Himid and Claudette Johnson personify the now changing post-war artistic canon. Their careers evolved against the background of important events in the recent American and European history and gained got an extra meaning in the era of #metoo and #blacklivesmatter, a proof of how much art is rooted in the social and political soil of its own/specific time.

#meetoo and #blacklivesmatter have contributed to another profound change in the art world, the current dominant trend of figuration sometimes drifting towards kitsch. Works depicting lives of people of color painted by artists of color or allowing glimpses into female habitus and subjectivity painted by female artists have become the prominent trend. We are facing an outburst of painterly variations on these subjects, which is extraordinary. The problem might be that these subject matters’ current relevance excuse the works from serious art-critical investigations and moreover, that any critique can be ‘cancelled’ using socio-political arguments instead of art theoretical, formal or art historical ones. Today, it is the social context that determines the artistic value, more than formal aesthetic considerations, as it is the social context related to feminism, multiculturalism and post-colonial guilt that exposes collectors’ and institutions’ progressive attitude.

This readjusting the Western art canon didn’t happen overnight but has been result of joint efforts coming from collectors, institutions, critics and scholars, represented in the book by the American collector and trustee on several museum boards Pamela Joyner, who has been championing African-American artists for more than thirty years, especially the ones working with abstraction. This shows in passing that creating a cultural, social and financial value is a matter of endeavors, struggles and collaborations of many different participants in the art world; great artists are not born great but created so by an entire system.

The recent rewriting of the canon has challenged yet another concept of the art world: art as progressive intellectual territory that is open-minded and inclusive. We know now that also the art world had been heavily biased, oppressive, and exclusionary. The reaction to these revelations is, well, reactionary: the institutions have become more dogmatic and fearful, with little tolerance towards opinions other than the standard woke catechism. Exhibitions of `called out’ artists have been cancelled, think about Chuck Close, Jon Rafman or even Philip Guston. Western art history departments cancel their art courses because they are too focused, well, on the Western art history, which, for instance, happened at Yale with their Art History Survey Course. New generations of curators and scholars with different agendas are coming to the fore and claim their power using their knowledge, skills, and the opportunity the need to vindication has offered.

PAUL MPAGI SEPUYA, A CONVERSATION AROUND PICTURES, 2019

These changes have influenced our relationship to the past, which has been shifting as well. The avant-garde of the early 20th century wanted to erase, at least ideologically, art history’s status quo as well as pre-existing artistic positions in order to start from point zero. To be modern meant to reject the past, that was the motto advocated throughout the 20th century. Today’s approach in the field of art is very different: we do not want to get rid of the past; we embrace it instead only to expose how flawed its judgments were so we can cut the past in pieces and stich it together anew. This very act of rewriting forms not only the long-overdue correction of the art system’s injustice, but it is also the claim to power of the new players who seek to decide about the central issues of the art system: who gets visibility and what is of quality.

LUBAINA HIMID, FIVE CONVERSATION, 2019

What about the art world’s morality? Although its official ideology still celebrates the critical anti-money and anti-capitalistic standpoint, the daily practice shows that relationships between artists and gallerists have become more transactional. Many artists have not only been enjoying, but also pursuing economic success. Today, it’s not strange to see artists wearing Balenciaga, flying business class and buying a house. The financial accomplishment is a welcome correction in my opinion, as artists should profit from their success as it is the case in other jobs. Mind you however, nowadays, when talking about being an artists, we are talking about a job and no longer about a vocation. Artists join and leave galleries when they think they can have better career opportunities; galleries announce new artists represented every week, so their rosters blow up in line with the inflated prices of young artists at auctions.

Contemporary art as engaging social, cultural, and financial asset continuously stimulates the growth of new institutions worldwide. Although Western system still dominates art production and valorization, Asia and Africa have increasingly claimed their importance. We have seen several notable private museums rise in places that used to be viewed as the art world’s periphery. The current enthusiasm for African art and the striking buying power of Asian collectors have certainly been driving forces behind the expanding global art world. It’s the new participants’ taste that has opened the doors to intellectually and visually accessible art at the expense of art historical relevance. I agree with Marion Maneker, art market specialist and one of the book’s interviewees, that ‘democratization’ comes not without danger since it is not easy to maintain both, the quality and originality when producing art on an industrial scale, but I also enjoy the tremendous energy and enthusiasm of the new.