Shirin Neshat

Published: March, 2018, YOU, ME AND ART

Marta Gnyp: Let’s start with your most recent project, your film Looking for Oum Kulthum. Why have you been so fascinated by this Egyptian singer?

Shirin Neshat: Looking back at my career I find that I have had a long obsession with strong Middle Eastern female artists. In my earlier photographic works I used the poetry of the well-known Iranian poets Forough Farrokhzad and Tahereh Saffarzadeh; later I made the film Women without Men that was based on a novel written by the legendary Iranian novelist Shahrnush Parsipur, and now with this film I pay a tribute to Oum Kulthum, the iconic Egyptian singer. So perhaps unconsciously I have been drawn to women who are not only brilliant artists, but also have lived difficult yet interesting lives. Each one of them seem to have challenged the traditional roles of women, and their journey as artists has been unpredictable, fascinating and highly successful.

MG: What was so specific about Oum Kulthum?

SN: In her case I was first and foremost drawn to the power of her music. She was an amazing singer; and without a doubt the most important and powerful artist of the twentieth century in the Middle East. Her music moved millions of people. It is unprecedented that a woman has reached that level of popularity as an artist, especially in that part of the world.

MG: Is your admiration a form of research into the complexities of artistic success?

SN: Indeed, there is always that unconscious sense of self-reflection on my behalf. I feel as an artist I have been looking at the trajectory of iconic women artists whom I admire, to learn about how they balanced their personal lives with careers; how they faced the challenges of being women artists living and working in male-dominated societies. So, in the end, by studying and incorporating their work into mine I not only pay tribute to such great female artists, I confront my own personal issues and dilemmas as another female artist from the Middle East.

MG: Are you identifying yourself with Oum Kulthum to a certain extent?

SN: I wouldn’t dare to compare myself with her, because she is a legend.

MG: Still, there must be some similarities between the two of you.

SN: There are. First of all, similarly to Oum Kulthum I have devoted my life to my work. Secondly, although she lived in a conservative and religious culture, she lived a truly untraditional life as a woman. She never had children and her marriage was only a marriage of convenience. In my case, I also lived an unusual life. I left my family when I was only seventeen years old, and later, after a short marriage, I raised my son alone as a single mother. So, both of us, like many artists, did not enjoy a nuclear family structure. There are other parallels, for example Oum Kulthum was always surrounded by her male collaborators, such as musicians and composers; and in my case, although I seem to make highly feminist work, I work mostly with a team of men.

MG: Why are you always stressing that you are a woman artist and not just an artist?

SN: If you look at my work carefully, you’ll find that all my protagonists and narratives are female. This is partially because I am a woman, therefore I relate more closely to issues of women, particularly those living in oppressive societies. And also, I take immense inspiration from strong women, mainly Iranian women who have been up against a wall for so long yet have remained resilient and defiant.

MG: It’s striking that you see yourself as Iranian, although you’ve been living in the USA for the last forty years, which means the biggest part of your life. Don’t you feel that you are American and that you are not in exile but at home in USA?

SN: It’s true that I’m not only an Iranian anymore, and that I have lived outside of my country for a very long time, but this doesn’t stop me from remaining an Iranian. I would say that I’m American in my lifestyle, education, and certain characteristics such as my independence. I’ve lived in New York since 1983, so I feel very much rooted in New York culture. But my emotional and psychological foundations are still deeply Iranian. I’m married to an Iranian, I speak Farsi daily, I’m part of an Iranian community, and my family still lives in Iran. So, my identity is complex. I’m not only an Iranian living in exile, I’m a native New Yorker and American. Slowly I find my work is moving away from the Iranian subjects; Looking for Oum Kulthum is no longer about Iran, but about me as an Iranian looking at an Egyptian artist. My newest project will be about America.

MG: I was wondering whether you celebrate your Iranian roots naturally or deliberately when you operate in the public space: you tend to wear heavy makeup, oriental earrings etc.

SN: It is precisely about being both – Iranian and American, two cultures that are in constant conflict; and how emotionally, psychologically, and politically I feel constantly divided between the two. And therefore this form of contradiction is reflected in my entire constitution, including my style which appears on the one hand very modern and minimalistic, yet extremely ancient, Eastern and almost tribal.

MG: Let’s go back to the moment when you arrived in the USA in 1975 to study art at Berkeley University in California. Was art a conscious decision or just one of the choices that you could have made?

SN: When I was a child, I always had this romantic interest in becoming an artist, without understanding what it really meant. I’d never been exposed to art in galleries or museums. All I remember is that from childhood I had an instinctive desire to be an artist and everyone at school called me an artist for making some silly drawings. Eventually when I came to the USA to study at Berkeley, I quickly learnt that I didn’t have what it took to be an artist. Therefore, that whole romantic idea of being an artist was shattered.

MG: Were you disappointed?

SN: The truth is that I was a very mediocre student, I was barely accepted to the graduate school. But I was smart enough to recognize that. When I came to New York from California I made no effort to make art for the next ten years.

MG: You worked at the non-profit organization Storefront for Art and Architecture. Did this time and the conversations about art shape you and give you the confidence that you needed for your work?

SN: I never related to the education that I received at art school; and never believed that artists are born naturally talented. I generally find it hard to accept that students in their early twenties would be capable of producing significant and meaningful work. I think that art stems from one’s collective life experiences, struggles, and responses to the world that we inhabit. Art cannot be entirely developed based on one’s intuition or simply an elaboration of art history.

MG: Are you saying that artistic education is redundant?

SN: I should not generalize since my opinion is uniquely based on my personal experiences. As matter of fact, as I have recently been involved in teaching as a guest critic at Yale University’s Photography department and I have met several students who are exceptional and brilliant despite their young years. So my whole argument could be wrong.

MG: What was it that brought you back to art?

SN: I went to Iran in 1990, years after I left the country and years after the Iranian revolution. I felt a deep connection to the country so when I came back to New York I started to make art again but without any specific goals or strategies. It was these few works that some curators found interesting, and so my career took off. By that time I had found the necessary maturity, a methodology, and, most importantly, a subject matter that I was passionate about, which related to the Iranian revolution, so I began to articulate my artistic voice and signature.

MG: You started with a romantic idea of art, abandoned making art all together in 1983 and then returned to it twelve years later, when after your emotional experiences in Iran, you started with the series Women of Allah.

SN: I had been working at Storefront for Art and Architecture for nearly ten years by then, helping program other artists and architects’ work; but I reached a point when I felt the urge to build my own artistic identity. This all crystallized when I started to travel to Iran again in 1990, when I got inspired by my discoveries, and my interactions with Iranian people whom I had lost touch with. Back in New York, I wanted to make sure not to lose this connection with my country again, so art became a form of an excuse, a link to keep my relationship to Iran alive even from a distance. In terms of form, I was thinking about how to develop my own visual language. Painting was totally irrelevant to my subject matter now, and although I had never been a photographer, I realized that photography would be the perfect medium for me because it had the realism I was looking for. I was especially taken by photojournalism. I started to collect images from newspapers and magazines, various references, and then next I went to a friend who was a photographer and asked him to shoot a few portraits of me. Soon some people in the art world showed interest in what I was doing. I remember submitting a proposal to a very small non-profit organization in New York called Franklin Furnace which got accepted. One thing led to another and my career got started.

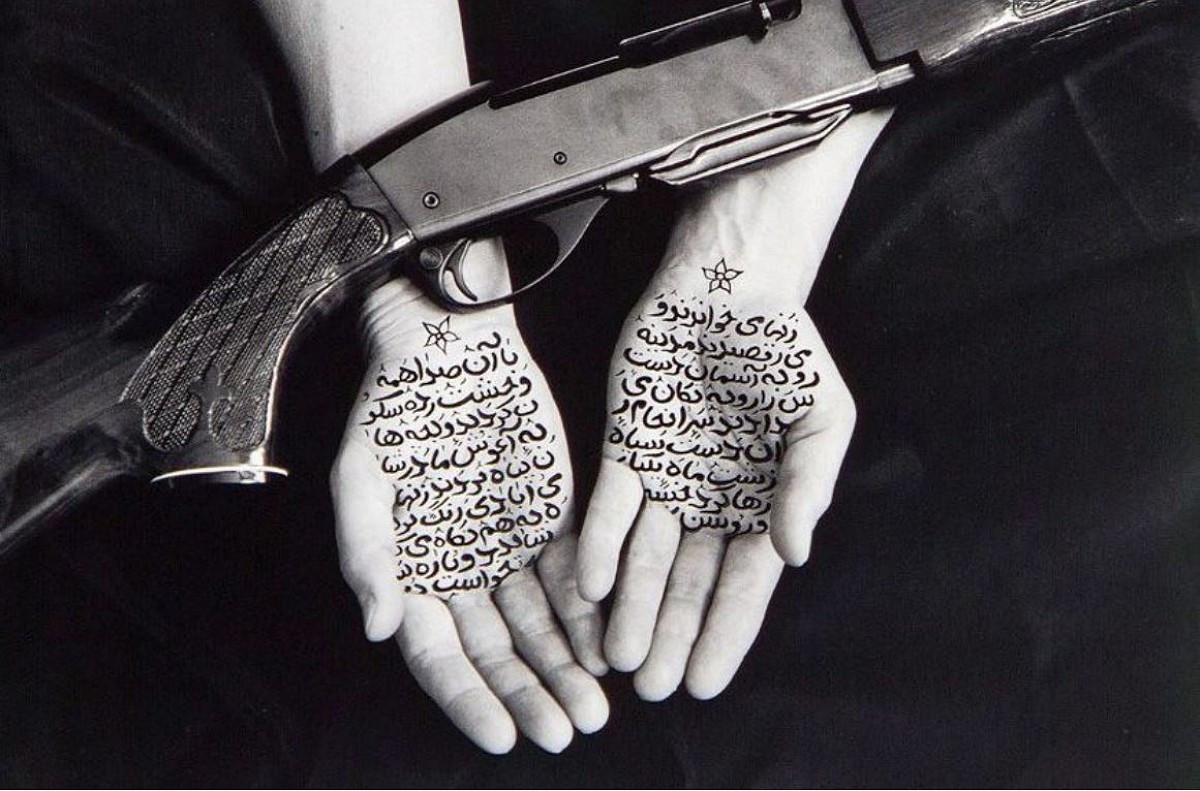

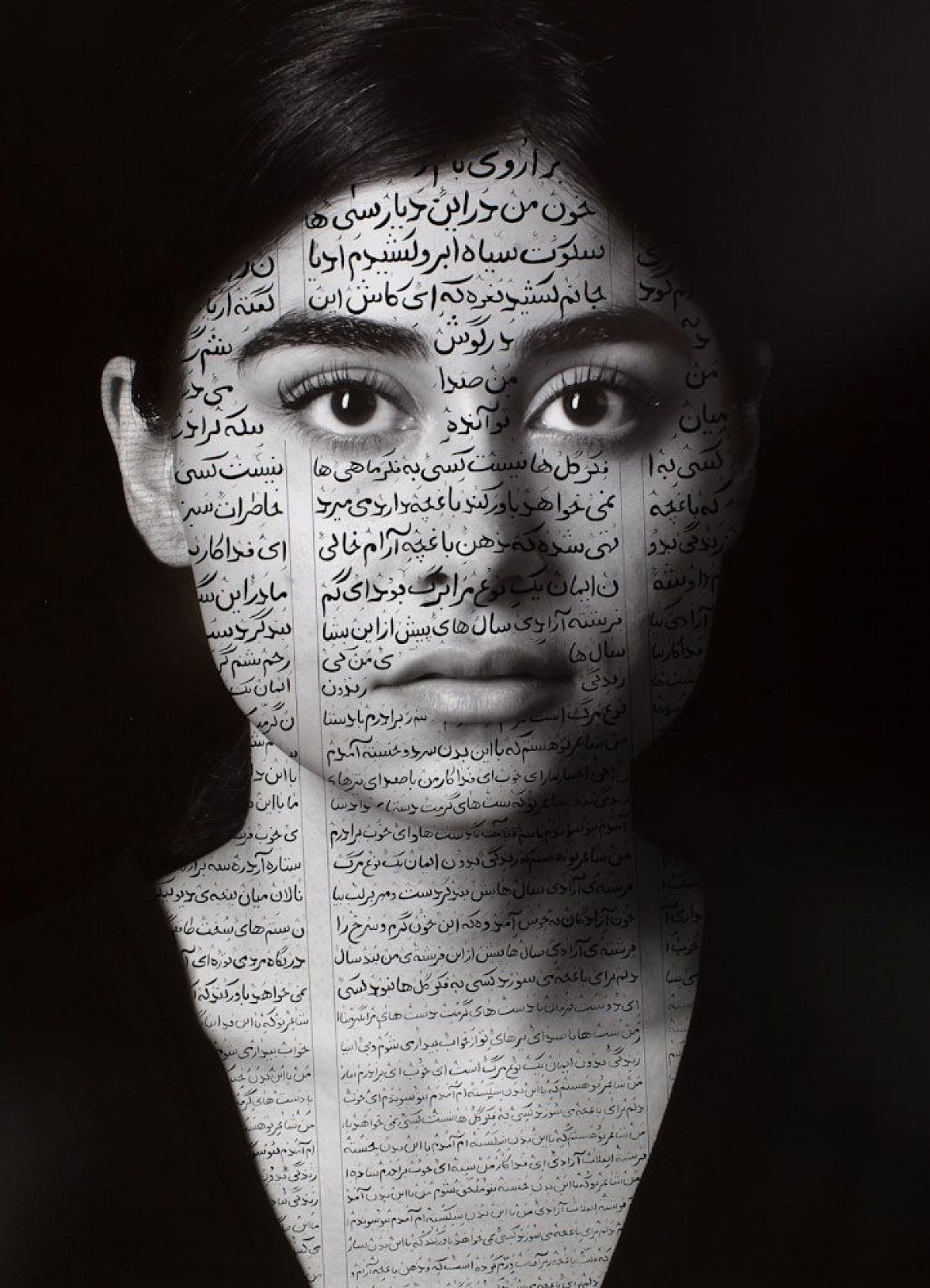

FROM THE SERIES “WOMEN OF ALLAH”

MG: I’m interested in the relationship to women that you captured in Women of Allah. I read articles about this series in the 1990s. In an early one from 1995 I found a quote – that I assume was yours “Chador as symbol of rebellion against imperialism,” while in 2017 you said that women are used as “the battleground for men’s ideology.” This is quite a change in thinking about the subject. At the beginning of the 1990s you seemed to be quite fascinated and terrified by what was happening in Iran, while your interpretation now is very clearly negative and rejecting political changes in Iran.

SN: All the works that I’ve done, Women of Allah and later The Book of Kings, are about raising questions as opposed to providing answers. It’s true that after twelve years of absence, when I first came back to Iran I experienced some kind of romantic infatuation with the revolution, but that changed very quickly. Women of Allah basically explored the mindset of a typical militant woman who was brainwashed and remained faithful to religious fanaticism and the Islamic revolution which had even institutionalized the concept of “martyrdom.” These women believed in the government’s rhetoric, that by returning to the idea of “veiling” they would be resisting the Westernization of their country. In many ways, putting the veil on – as imposed by the Islamic regime – or taking it off – as ordered to modernize the country during the regime of the Shah – shows how Iranian women throughout history have become the battleground for men’s rulings and ideology.

MG: Were you criticized because of your ambiguous attitude?

SN: Oh, yes. Especially by Iranians who were against the regime and thought that I made this work to support and endorse fundamentalism and the current government. While, the work was made to show my understanding and reading of what had transpired in the country during the post-revolutionary era without making any judgments.

MG: How do you keep your convictions and beliefs outside your work?

SN: What is in the work is my curiosity together with the information that I gather through my research. I’m not a religious person and have never been interested in sharing my own personal beliefs and agendas with the public.

MG: For Women of Allah and The Book of Kings you have chosen similar visual solutions – black-and-white photography, texts in Farsi on their bodies – yet a lot has changed. If you look at the two series you see the change in society.

SN: Both series are works of fictions. The Islamic Revolution (1979,) and the Green Movement (2009) are the two single-most important political events in modern Iranian history since the coup d’état of 1953, which was the period we captured in the movie Women without Men. I never thought history had such a significance place in my work and thinking process. But now, when I look back, the Women of Allah series depicted the religious fervor that transformed the Iranian society from a monarchy into an Islamic Republic after the 1979 Islamic revolution, when religion began to dominate and rule Iranian society. Later The Book of Kings in 2011, depicted a different uprising, the green movement, thirty years after the Islamic Revolution, when we were faced with a changed society. This uprising was led by a new generation of Iranians who were not religious and who were modern, educated, and forward-thinking. Furthermore, this generation of activists were not interested in overthrowing the government but in simply demanding basic democracy and human rights. Therefore, The Book of Kings is a very accurate portrait of current Iranian society, where religion is no longer as dominant a factor in the country as it used to be.

MG: How come your work has never been prosecuted by the Iranian government?

SN: As far as I’m concerned, I’m only a poet. I’m not attacking the government. I don’t make polemical works. I’m not sure why the government has problems with me and my work, but I don’t consider myself a political activist.

MG: I was thinking about Salman Rushdie, who also writes fiction.

SN: He touched on something that became sacrilegious. I have never been interested in offending people of religion. I may have been publicly vocal against the government to object against their human rights records but I have never used my art as a platform to promote my own ideals.

MG: Let’s go back to New York of the 1990s, when you started to make your photographic series and you were first noticed as an artist. What was the artistic situation in New York like at that time when your career took off? With whom did you feel connected?

SN: In the mid-80s there was a lot of excitement in the East Village, a true bohemian cultural moment. The scene was exploding with graffiti art, rap music, break dancing, and great artists were at the pinnacle of their careers, such Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, and Jean Michel Basquiat. I found myself at the center of this underground art scene. I lived in the East Village and became friends with many artists, especially some graffiti artists, and went to many well-known clubs. Eventually I married Kyong Park, who was also very much a part of the underground scene of New York City, and founded the small alternative space called Storefront for Art and Architecture in 1983. But, unfortunately, in early 1990s things changed and that fascinating scene transformed quickly into a more commercial and pretentious art environment.

MG: Your ex-husband Kyong Park opened Storefront where you worked as well.

SN: Yes, I spent ten years working with him. And through my work at the Storefront I got to know and work closely with many great artists and architects, such as Kiki Smith, Alfredo Jaar, Vito Acconci, Mel Chin, David Hammons, Steven Holl, Jean Nouvel, Coop Himmelblau and others. The environment was exciting and productive, always about ideas and the process and never about money. I always say that my true education came from my years of working at Storefront and not from my education at art school.

MG: The work you were making in the ’90s was quite different from the work of the others. Did you feel part of a group?

SN: It’s true that I was very much on my own in terms of the subject matter and the way I was exploring the medium of photography. Plus, at that time I became very intimate with a team of Iranian collaborators, including writers, musicians, and cinematographers and we created our own independent community. We were working and travelling together all the time. So, I slowly moved away from the Storefront group and became surrounded now by my new Iranian colleagues.

MG: Your personal life was very much connected to the development of your work.

SN: Very true. Once I decided to be an artist again, my relationship to both my husband and Storefront strangely ended. I became romantically involved with Shoja Azari who was one of my main Iranian collaborators, and to this day we continue to work and live together. All of my video-based work, as well as the feature-length films have been made in collaboration with Shoja.

MG: Switching into making films must have been quite an enterprise.

SN: By the end of the ’90s I had made so many photographs that I felt the urge to push beyond my signature work, which by now had become somewhat popular, and to experiment with the moving image. So together with my team we went to Morocco and started to make a number of video installations, which was a huge departure for my work. I was now able to leave the notion of studio work behind, and incorporate, landscape, music, choreography, and narrative into my work. Most importantly, I learnt to direct films.

MG: Rapture was your first important video. Did you lean on your photographic knowledge to make it?

SN: I would say Turbulent and Rapture were both my first important video works, and clearly aesthetically and compositionally they heavily borrowed from my black-and-white still photography. Every frame of Rapture is a photograph with the exception that there is always a thread of a narrative. For me these two videos were the opening to a wide range of possibilities in the art of video installation and cinema. So the team and I went on to make a number of other pieces across the world from Morocco to Turkey, and Mexico.

MG: Is film is your favorite medium at the moment?

SN: The answer is yes. I think that film is my favorite medium at the moment because I can continue to make photographs within the construction of a film. Although the only thing I enjoy in the process of being a still photographer is the solitude of studio work, something that is lacking in filmmaking since it is such a collaborative medium by nature.

MG: Was the Golden Lion for your video Turbulent at the Venice Biennale in 1999 your artistic breakthrough?

SN: Absolutely, receiving that prize was my official entrance into the contemporary art world on an international level. Then later, in 2009, receiving the Silver Lion for Best Director, at the Venice film festival helped my film career immensely.

MG: Recently you have even become an important voice fighting for more women in the film industry? I read a few articles about you claiming more space for women in the film industry.

SN: I wouldn’t say that I’m an advocate for women in the film industry. There aren’t a lot of women making films in the USA, and I was simply asked for my opinion, but the situation seems to be slowly changing. I must say, though, being a Middle Eastern woman filmmaker has helped me get a certain amount of attention and recognition, so I can’t personally complain of discrimination.

MG: What are you working on now?

SN: I’m working on a new feature film which I hope to shoot in the United States in late 2018. I’m also preparing a major exhibition that opens at the Faurschou Foundation in Denmark on March 16. It’s about the process of making the film Looking for Oum Kulthum.

MG: What approach did you chose to tell the story of Oum Kulthum?

SN: It’s a film inside a film. It’s a story about the challenges of an Iranian woman artist/filmmaker making a film about the legendary Arabic singer Oum Kulthum.

MG: Which means that this exhibition will be about making a film that is actually a film about making a film. Was it difficult for you to make the film since Oum Kulthum was Egyptian and you Iranian?

SN: There were multiple challenges in making this film. First of all, it was extremely courageous as a non-Arab, to dare to make a film about the biggest icon of the Arab world in the twentieth century especially without speaking any Arabic. Secondly, the style of the film became an interesting challenge of interweaving the many different layers of narratives; the biopic/period part of the story of Oum Kullthum; the production and the director’s personal story; together with dreams sequences and edited archival footage. Of course, I knew Oum Kulthum since childhood since she was well known across the Middle East but I spent nearly six years in research, development, and the final execution of the film.

MG: How do you explain her popularity?

SN: First of all, she was blessed with a tremendous voice and technical vocal training that to this day no one has been able to master. And although she was not beautiful and even rather masculine, she was able to reach deep into the heart of her audience. She sang very emotional love songs that threw people into a state of ecstasy. She was known to be loved by men, women, poor, rich, secular, non-secular, Muslims and Jews. Her popularity at the end of her life reached the point where four million people poured into the streets of Cairo to mourn her death. I must also mention that toward the second part of her career she became very patriotic and helped her country through economic hardship and political crisis. So the Egyptians worship her and have a rare affection for her beyond her musical gifts.

MG: Her music is full of repetition.

SN: Her style of singing connects to a more mystical history of music in the Islamic world. Described as “Tarab,” this is a commonly known terminology for describing Oum Kulthum’s music and how she repeats lyrics to the point where her audience reaches a form of orgasmic experience, losing all sense of time and place.

MG: Why did you decide to make this exhibition about the making of?

SN: The exhibition came as unusual invitation by Faurschou Foundation. I actually found it interesting to find ways to share my process of making a film with the public. In the end, the exhibition focuses on how a visual artist might approach making a complex film such as Looking for Oum Kulthum. Therefore, the exhibition becomes about the portraits of two artists: one a contemporary living artist, i.e. me, and the other the historical legendary artist Oum Kulthum.

MG: Did you go to Egypt yourself?

SN: Yes, I went a few times with my Egyptian colleagues and collaborators. We met and interviewed Oum Kulthum’s family, her adopted son, and many other experts. Today I think after six years of research, I must have one of the largest archives on Oum Kulthum. Sadly, in the end, we didn’t shoot the film in Egypt due to political reasons. We shot it in Casablanca, Morocco.

MG: How did you finance it?

SN: I had to raise some of the money by selling my own artwork. Otherwise, the main support came from Middle Eastern private and government sources, as well funds from European countries such as Germany, Austria, France, and Italy.

MG: The production of the film took six years, comparable to Women without Men. How do you divide your time during such a period of time?

SN: Normally, through such long production periods for movies, I keep busy with other activities as well. For example, in 2017, while editing the movie Looking for Oum Kulthum, I also directed a major opera, Aida, held an exhibition at the Venice Biennale, and had a solo gallery show in New York and Istanbul.

MG: You have given music a very powerful role in your other films as well.

SN: Music has played a major role in my film-based work. I strongly feel that music is a rare art form that transcends cultural differences and affects people on the deepest level without the need for translation. Also, music has helped me to emphasize the emotional nature of my work and to some degree neutralize some of the socio-political themes.

MG: Last year you directed the opera Aida at the Festspiele in Salzburg. How was it for you to make an opera?

SN: Fantastic! Although an entirely new experience working with a new art language; in many ways it was not unlike making a long video installation where one works with the fusion of image and music. Although I was rather terrified at the beginning being given such a responsibility. I tried to trust my own artistic logic and aesthetics and gave it my best.

MG: With your Iranian background you could give another interpretation to the story of Aida.

SN: Aida is a very controversial opera, heavily criticized and regarded as orientalist by many Middle Eastern intellectuals. Its depiction of ancient Egyptians and Ethiopians is quite barbaric and racist. Yet the main story revolves around an enslaved Ethiopian princess living in exile in Egypt and in love with the military’s commander-in-chief who invades her country. The classic Aida has been heavily criticized for its cliché representations of Arabs and Africans yet has been hugely popular with the public. So I had the difficult task of making a reinterpretation of Aida that addressed all its critics, yet was still enjoyable and had the same level of grandeur as the original.

MG: I’ve seen photos of the set: you used a very simple cube and projected videos onto it.

SN: I took a very minimal approach. The stage was very sculptural and transformed every time it turned.

MG: Could you tell me about your next project?

SN: It will be a film about an Iranian woman living and working in Midwest America, a mostly white, poor and Republican town. The film is inspired by my own experiences and interactions with the part of America that is removed from major cities and the Americans whose relationship to foreigners, such as Muslims, are reduced to the information they gather in the media. I find the cultural clash between someone like myself and the Americans living in such areas so vast, complicated, and interesting that I finally decided to make a film about it.

MG: A film about the clash of cultures…

SN: …Yes, culture clashes… Yet, a shared sense of humanity and good values that prevail underneath our differences.

MG: Whom are you making this film for? Not for these people?

SN: I’m not sure. I don’t usually think about that question when I’m making my films, but certainly I hope a diverse group of people will see this film, which will be in English for a change; and I do think the subject matter is rather timely and relevant today.