Sean Scully

Published: January, 2022, YOU, ME AND ART

Marta Gnyp: You were born in Dublin, raised in London and now you are living in New York. How do you cope with all these different national identities?

Sean Scully: When you say “identity” in this context you only mean the identity of your passport, and to me that’s just a technicality I somehow circumvent. I’m against nationalism.

MG: I’m curious to know what made you get your American citizenship in 1983.

SS: Well, I took it because I’d lived in America for eleven years by then. It seemed a little strange to me to be camping out in somebody else’s country and always using a foreign passport.

MG: Being Irish or being American is not only a matter of passport, obviously. There are a lot of cultural elements that you are blessed or poisoned with coming from one country or the other…

SS: Yeah, of course, Irish-American is probably the classic combination. When I came to this world we lived on the street; we didn’t have a house. I really am a gypsy by breeding. So, for me the change from one house to another is normal; it’s like putting my donkey in front of my caravan and saying, “come on!” – and off we go again. That’s how I started my life. By the time I was eight, I’d lived in about eight different houses. My family had a lot of singers and storytellers in it; nobody was formally educated like me, nobody went to university. They were all travelers really and that’s what they call them in Ireland travelers, gitano. We all constantly went back and forth between Ireland and England. Ireland and England are very mixed up. Most of the great Irish artists like Francis Bacon, Samuel Beckett, and James Joyce are what you would call Anglo-Irish, which is also a very interesting mixture because you’ve got fire and discipline.

MG: Fire is Irish and discipline is English, I assume?

SS: Yes, and that’s basically what you have in my work.

MG: I read some tragic stories about your grandfather, who committed suicide in jail where he landed after participating in an uprising in 1916, which, by the way, paved the way to the independence of Ireland.

SS: My illegitimate grandfather committed suicide because he was sentenced to be shot – and he refused to be shot. He killed himself as an act of defiance, so I consider him to be a great hero – and a model for me. My father was also a deserter from the war, which I’m very proud of because I don’t think war is any good at all for anybody. That’s one of the things that I detest about America – that America is so militarized. It’s a detestable aspect of American culture.

MG: Maybe because they’ve had much fewer wars in America than we’ve had in Europe.

SS: Yeah, so they’re still stupid.

MG: Speaking of differences between different countries, do you see a different reaction towards your work in America and in Europe?

SS: I do. It’s taken a very, very long time for me to become really big in America. It happened in Europe faster. I think that Europe is more interesting for art now anyway.

MG: Why?

SS: Because it’s a unified landmass with incredible sophistication. It has people like you in it, who are asking questions all the time. America is much more of a capitalist, product-oriented society, whereas Europe goes into the reasons for things. That suits me perfectly because I’m a very philosophical artist. What I used to say was that I always had a problem north of the equator. My work was very much appreciated in Spain, Italy, and southern Germany.

MG: In the Catholic parts of Europe.

SS: Yes, that’s where it’s really embraced. I always had a problem in the Netherlands and Sweden, because my work is too dirty.

MG: Your work tends to be – I wouldn’t dare to say religious but kind of transcendental, which is problematic in these Protestant countries.

SS: It’s problematic, because they don’t trust it. I had the same problem in England because they don’t trust that profound, metaphysical emotion, whereas in America it’s accepted.

MG: Don’t you think that one of the weaknesses of Europe is exactly this constant self-reflection and self-criticism? They don’t have it that much in America.

SS: No, they don’t, which is part of the reason for my attraction to America because I’m a very action-oriented person. I’m a maker. I don’t mess around much when I make things. I go in the studio and make a painting. I’m not a person who’s inhibited by doubt. In America they used to describe Joseph Beuys as “European bullshit,” which means, “you’ll never get to the point.” There’s something to be said for that criticism, but, on the other hand, the problem with America is that you have a George W. who invades Iraq first, as an action, and thinks about it afterwards. I would say it’s better to think about it first before you do something like that – and not do it and say stupid things like, “We’re gonna smoke ’em out” after killing hundreds of thousands of people and creating three million refugees. I think that the doubt that Europe has is a doubt that’s been earned, and it can be very humanizing because in Europe we’ve learned to put the value of human life before all else. Sure, it makes us seem indecisive, but so what? It’s not a competition to see who will be the first to reach a conclusion. I think people who jump to conclusions or have hardened opinions are really mostly loud-mouths. They appear strong but it’s actually backed up by emptiness, and this is the counter-argument.

MG: Well said. Clearly, you are a convinced pacifist. I read, though, that in your youth you were part of a street gang and that you excelled at karate. Is this a way of preparing yourself for the worst-case scenario?

SS: Going with a gang is environmental. You basically had to be in a gang for survival, and it was exciting. I was in a big street gang. We got into a lot of fights that were basically wars over territory, but that was something I rebelled against. Karate is, of course, violent when you fight, and I had a lot of fights, but at the same time it’s noble, and disciplined – and you’re a knight. That’s very attractive to me, because I’m full of all these myths from the past.

MG: Do you still practice?

SS: I practice a little bit on my own, but I’m too much of an individual to be in a cult for very long. I’ll break with it because they ask you to give up your individuality, which I think is a crime.

MG: Let’s talk about your work, which is full of individuality. You’ve been making abstract paintings for a very long time. What drew you to abstraction?

SS: I wanted to make art that was unifying. I want to stitch the world together and break down differences. I see myself as an emissary of peace and understanding – and abstraction is part of that because it is a language, particularly the way I use it with these basic structures, that are common to all people.

MG: Everybody can project whatever they want onto your work.

SS: Everybody can project whatever they want onto everything, including my work. [both chuckle] My work has structure, it’s got integrity, it’s serious and deep, and it comes from essentially Northern Romanticism mixed in with primitive structures that come from Africa or South America. I wouldn’t say that you could project onto my work that pedophilia is a good thing, so I don’t think it’s true to say that you can project anything onto my work. It stands for certain humanistic values. There’s an element of classicism in it. The titles are strong indications of the meaning of the work. You can project what you want but the work has an opinion also. It’s not entirely neutral – it’s humanistic.

MG: You give hints about how to interpret them?

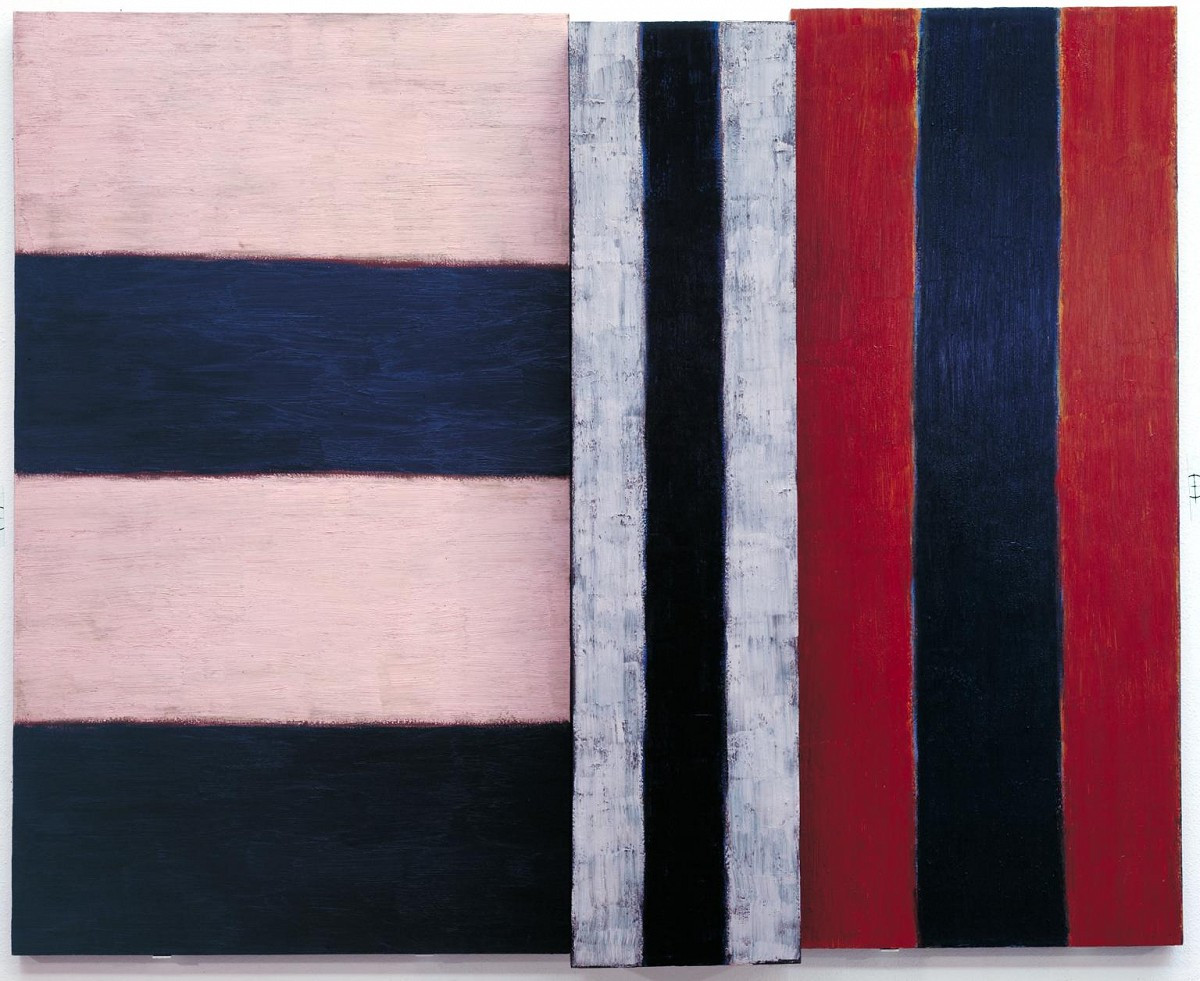

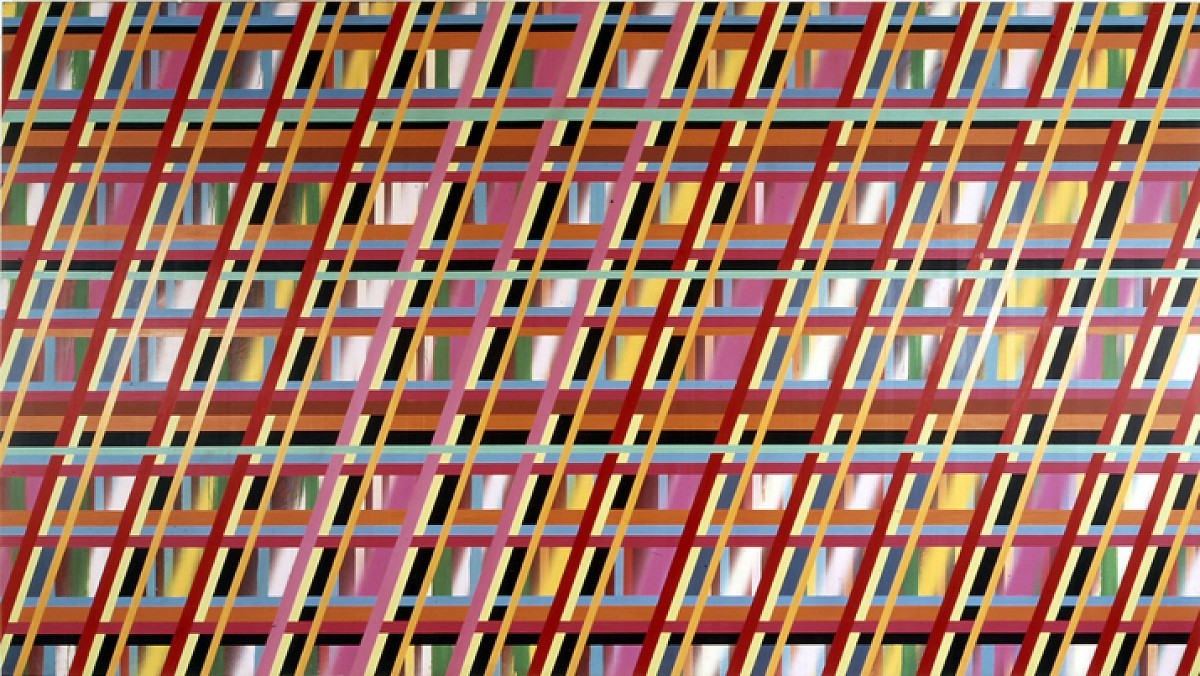

SS: Yeah. My work is a way of emotionalizing or individualizing or humanizing the structures that actually dominate us. That’s really the agenda in the work. We are living in a world made by walls and grids, a world of geometry and hyper-structures. My work is a way of dealing with that, and making it poetic, deep and profound, and in a way overcoming its tyranny – because order without pause is dangerous and leads to fascism. Fascists love geometry, but they like it nice and clean. They don’t like dirty geometry like mine or geometry that’s got things in it that are wrong. My geometry is more like Paul Klee, a little errant.

MG: You mentioned the grid, a charged term in recent art history. Do you connect your work with the modernistic Greenbergian idea of painting?

SS: No, I’m misusing all that sense of order. For example, I made a painting called Falling Wrong, and people have been very bemused by this title. In relation to the Greenbergian idea it’s a mistake because that idea is all about harmony, taste, and perfection – and my work has nothing to do with perfection. When things are wrong they’re right, and when they are right they’re wrong. I’m constantly questioning authority and order.

MG: When you started painting in the 1960s, painting was declared dead, which probably meant there was no interest in your painting whatsoever.

SS: That’s right.

MG: How did you survive this? It must have been very frustrating to hear “painting is over and done with and obsolete.”

SS: That’s their business – it’s not my business. I’m hyper-individual and I’ve always pictured myself in highly rebellious terms. I stand for things that could be threatened. Anytime something is being destroyed, I will always try and save it. It’s an instinctive response.

MG: That sounds fantastic as an idea, but I can also imagine what it’s like when you’re a young artist, starting your career and then find there’s no interest in your work. How did you cope with this?

SS: Well, I don’t mind being in a minority.

MG: But how did you survive from a practical point of view?

SS: I survived with my spirit because my spirit is very strong. I’m not really destructible. I’ve worked since I was thirteen and I’ve done every kind of job you can imagine and didn’t mind making my paintings when I got home. I never expected to make money. I never expected my life to be like it is now. That’s not why I went into painting. I thought that it was a very profound, existential, heroic position in culture that was necessary, so that sustained me.

MG: Did your art school give you any problems for choosing painting?

SS: When I went to Newcastle University in 1968, it was entirely conceptual. There wasn’t one single person making paintings. There was a huge corridor where students were allowed to hang their paintings, but the students thought it would be very clever to not hang their paintings as an act of, you know, “Fuck off!” So I started making my paintings and hanging them on this wall. The students, first of all, thought I was an idiot or thought that this was a joke. But as time went by they got jealous, and then started making paintings and putting them on the wall – that’s how human beings are. It only takes one person to change the world.

MG: That’s a very nice story with a double message. Firstly, that we need strong individuals to change but also that people are extremely inclined to sheep behavior. I’m curious about what happened after your studies when you went to Morocco, which turned you to abstraction.

SS: It wasn’t that it turned me to abstraction because at that time I was already making abstract paintings like woven baskets. I’ve always been very interested in weaving – already as a boy I was weaving, knitting, and making mats for the table, which is traditionally considered to be a female activity. When I went to Morocco I saw a different geometry. The geometry I had seen and studied before was that of Joseph Itten, Bauhaus, and Suprematism, which was a geometry of order. Whereas in Morocco I saw a geometry of emotion, movement, and spirituality. Something opened up in me through this, so when I came back I started making striped paintings that were very repetitive and very rhythmical. This trip to Morocco transformed me. I ended up wearing a djellaba and sleeping in it on the ground. I was so in love with it that I had difficulty coming back.

MG: It sounds like a very spiritual experience.

SS: Yeah. It was absolutely transformative.

MG: Then you found your visual language which you have pursued until today, more or less.

SS: Yeah. The basic unit of what I’m doing, instead of the figure as it would be (let’s say) in Lucian Freud, is the stripe. I put the stripe in place of the figure because I used to be a figurative painter – a good one, too. People loved me in England for this and were so upset and angry with me when I decided to make abstract paintings.

MG: Have you never been tempted to go back to figuration after that?

SS: I just made twenty-two paintings of my son on the beach. My son has really again transformed my life – made me into a different person. If you had talked to me fifteen years ago, you would have been dealing with a more truculent, troubled, moody person. The arrival of my son has lit up my life. I wanted to make paintings showing him on the beach where we go every year. The only thing I could do really to immortalize this was paint it. So I made twenty-two large figurative paintings.

MG: Will you keep them for yourself?

SS: I keep them for us but I like to show them. I think that Olga [Tsviblova] is going to show them in Moscow [at the upcoming exhibition].

MG: What role does religion play in your paintings? You recently also donated a lot of paintings to the monastery Montserrat in Spain. A very meaningful gesture connected to eternity, but also the eternity connected to religion.

SS: Well, I never said that I don’t believe – I’m a believer. And someone once told me that I was a Hindu because I love all religions. I’m a fusionist in the end. I talked about this once in a lecture in New York, and there was a lady in the audience who was driving me crazy, and she kept saying, “what do you mean by all this ‘fusion’?” In the end I said, “Interracial fucking.” And then she said, “Ah, okay!” [both laugh] I suppose I’m a Catholic with a very strong Zen underpinning. I’m very tolerant of all religions and I think that religion is a higher place that we want to go to, that we will ultimately and hopefully get to. I think hopefully we will evolve into more unified, kinder, spiritual beings, and my work is part of this struggle.

MG: Your work is done by you – by hand.

SS: All of it.

MG: You don’t have any assistants that paint for you?

SS: I don’t have slaves like Jeff Koons.

MG: He pays them, though.

SS: My admiration flows over.

MG: Is it important to you that the work is done by your hand, that it’s connected with your mind and heart?

SS: Yeah. It’s the unified action. It’s the highest form of intelligence according to Socrates.

MG: It means that you are productive, but also limited in your output. I read that you’ve made something like 1,400 paintings. Probably now it’s like 1,500.

SS: Maybe.

MG: Do you keep part of them for yourself?

SS: I’ve got a big collection. This is something I like to have. It makes exhibitions very easy, because I go up to the mirror, and I ask myself if I could borrow this painting, and then I look back at myself and then I say, “Alright.”

MG: Did you take this into consideration from the very beginning and keep paintings from the early stages of your career?

SS: Early on it was easy to keep them because nobody wanted to buy them. It was in the early ’70s in England when I realized that I was in the wrong place at the wrong time because nobody was really interested in what I was doing. That precipitated the move to America where people became very interested. In the ’80s I got very famous in New York and had a huge waiting list for my work. You could say that in the ’80s I was the acceptable face of abstraction.

MG: Who was your gallerist at that time in New York?

SS: David McKee. He also represented Philip Guston. As people made a lot of connections between the way I paint and the way Philip painted it opened museum doors for me in America. Then it was harder for me to keep my work because everybody had a story about why they should have a painting. Like somebody says his wife’s birthday is next month, and he wants this painting – what are you gonna say? You can’t really say no.

MG: Who was more important for your career: institutions or private collectors?

SS: I’ve always been in favor of institutions. I want my paintings to be in museums because I think they are for the people.

MG: Museums don’t have so much money nowadays.

SS: No, you have to help them. When you write the numbers out, you have to knock the zeros off until the faces of the curators get kind of optimistic and lighter. As you take the zeros away it becomes more possible.

MG: Are you taking the zeros off for the important collectors?

SS: No, because they can afford what they want.

MG: What about your fascination for China? You’ve recently had five exhibitions in China.

SS: China, in particular, is a country whose people could be affected very positively. They’ve come out of a terrible past, partially precipitated by colonialism and exploitation and they came out of abject poverty. Now they have to handle this sense of freedom, that the people want, in a way that doesn’t cause catastrophes. I’m interested in this process and in contributing to it. I’m bringing something positive from outside that’s not critical of that, but wants to assist in this process, because beating somebody up from the outside is rubbish. It causes isolation.

MG: You’re an outsider who can act because you are not involved in politics over there.

SS: What’s really interesting about China in relation to abstraction is that abstraction was banned in China. This shows the power of abstraction because they were right to be afraid of it. All fascists are afraid of abstraction because abstraction provokes free thinking. This is exactly what they don’t want. Furthermore, you can’t edit abstraction because if you look at one of my paintings, which part are you going to leave out? None of it, or all of it? If you take out one of the stripes, it won’t change the intention of the painting. They were afraid of it, because they couldn’t edit it. Since it provokes subversive thinking – and it is subversive.

MG: It is a kind of Trojan horse because it looks so harmless.

SS: That’s exactly right. It’s a Trojan horse, and it’s filled with naughty thoughts. [both chuckle]

MG: What about your student Ai Weiwei who has a completely different approach to China? Was he angry with you for collaborating with China?

SS: No, he loves me. He came up to my opening the other day in Mexico City in Luis Barragán. Ai Weiwei invited himself and his family. His son played with my son and he kept pouring me huge glasses of whisky. it was terrible but funny. I don’t drink hard liquor but he kept coming over with glasses of whisky. [laughs]

MG: Do you like teaching?

SS: Well, I like affecting things – and teaching is part of it. And all great people, including Mahatma Gandhi, have been teachers because they want to affect change.

MG: It doesn’t distract you from your own work?

SS: No, it doesn’t stop me at all. It’s another activity. It’s like writing or talking to you. I’m talking to you now and I’m not painting, isn’t it awful? [chuckles]

MG: You’ve been in the art world for longer than forty years now. What, in your opinion, has been the biggest change, if you look at it from this time perspective?

SS: The change in my lifetime has been massive. I’m pre-electric, when I was a child, we had gaslight. When I thought of being an artist, I thought that I would make my paintings and I would maybe have one retrospective. In the meantime, I had about twenty. What’s happened in the art world is that art has become powerful because art has, in a sense, replaced religion. Art is a great force for good that has become hugely powerful. I was talking with Bono about rock ‘n’ roll once, and he said that rock ‘n’ roll was invented to change the world. He was really talking about himself, but I think that art now is changing the world because its power gives it enormous influence, which it lacked thirty years ago. It’s become an industry as powerful as the music industry, and because of technology, images, opinions, thoughts, and ideas are transmitted without barriers. You can jump over borders, which is exactly what I want to do because I want to knock them down. [chuckles] And art has become like rock ‘n’ roll.

MG: You are absolutely right that art has become very popular, but the question is: Are people really interested in art or are people interested in a kind of entertainment related to art, which is not bad by the way? Art has always been very elitist, which is not bad either.

SS: I know. I was listening to somebody talking last night about a moving image on a wall in a lobby – that it was more engaging to people than a static image because the static image was easier to ignore. This guy was talking about the destruction of painting by technology basically. But then a woman said, “Yeah, it’s only constantly distracting because it doesn’t have any art in it. It’s just something that you look at as you walk by. It doesn’t mean anything.” And she was right. There are going to be different levels of experience – and art is elitist. The conversation that we’re having now is very elitist, dense, and profound. It’s about history and culture, and where we’re going as a people. Of course, people are not interested in that all the time, but some of that, a residue of that, is moving into the culture.

MG: What exactly do you mean by the comparison between what happened to music with what is happening now with contemporary art?

SS: As art becomes more popular, it has become in a sense more like rock ‘n’ roll. OK, most of rock ‘n’ roll is like bubblegum music: “I love you, I love you, please don’t go! You’re making me feel so upset,” and on and on and on. But it has an attitude, and the attitude has affected culture and made culture more liberal and more open. I think the same thing is happening with art. In the music business, for example, there are still people who are making serious stuff, like, Agnes Obel, who we discovered recently. It’s been a force for good. If you listen to Bob Dylan or The Beatles, and then you listen to Frank Sinatra, Frank Sinatra’s like bowls of treacle – “Strangers in the Night”. “All You Need Is Love” is a message.

MG: Do you think new technology, like online images, has also been important for your art? Do you also notice that this availability of images online is good for you?

SS: Yes, it’s made art powerful. You can go to my church on the top of Montserrat, but there you get fourteen people a day who can see it as a first-hand experience. However, the images of it are also very powerful, and have an influence. I’ve never been to Machu Picchu but I certainly can feel it in some way when I see the images. I can feel its spiritual power, and that’s important. I think it serves me particularly well because my work is quite repetitive like LEGO – it fits in the computer world, and it fits in the romantic world, which is, of course, exactly what I want.

MG: If we think about the changes in the art world, what do you think about the position of the artist? Before, the artist was avant-garde, bohemian, romantic, revolutionary, and nowadays artists are quite different, you mentioned Jeff Koons before. What do you think is the position of the artist today?

SS: Of course, artists are different, like lots of other things. When I talk now, I’ve noticed that the audiences are bigger. For example, I had a show in Moscow and there was something like 350,000 visitors; mostly very young people. Not that I think that younger people are better than older people – it’s very interesting that there’s a huge hunger, and it was wildly successful. Nowadays the artist is no longer a kind of traveling gypsy or an existential figure in an attic – that’s over. Now, we are more like Rubens, who was the ambassador to London and a powerful figure. And I think now art is more like that. I can’t think of another age when art was as powerful as it is today, because it’s completely out of control – it’s totally free. If you stop it this way, it’ll go that way – it’s like water. That’s my sign by the way – water. It’s unstoppable.