Sarah Lucas

Published: June, 2014, ZOO MAGAZINE #44

Together with her friend Julian Simmons the British artist Sarah Lucas has recently launched the book titled ‘Tittipussidad’. The book – an artwork in itself – is a combination of photographs of both artists and their works during their inspiringly productive recent journey through Mexico.

Marta Gnyp: The idea of the book relates somehow to the house of Diego Rivera in Mexico.

Sarah Lucas: Diego built Anahuacalli to house his collection of pre-Hispanic artworks. It’s built in an area of volcanic rock, out of that rock, which is dark, almost black. The design was based on Aztec temple designs. The largest room was intended as his studio. It currently displays some of his very large cartoons. He also intended the building to be his, and Frida’s (Kahlo), tomb. As it turned out, the President wanted Diego’s remains for the Hall of Great Men. Frida’s ashes are in a jar in her own house. Most of the artifacts in the museum are figures or pots – rather than abstracts as you suggest.

MG: You wanted to visit this his house and see this collection? How big is it?

SL: About 60,000 objects, of which probably 20,000 are on display.

MG: Why were you so fascinated by RIvera?

SL: For years Julian and I had had the idea of going to Mexico and responding to its early artifacts, ancient rather than modern. The project in Rivera’s museum was a great opportunity to realize this wish.

MG: Did you find in Mexico what you were looking for?

SL: Naturally the Museo National de Antropologia was our first point of call. We also visited Diego’s house, Frida’s house, and Trotsky’s house. In this way they began to tell their story to us. I had no particular plan before arriving in Mexico. So, tracking down material was also a part of our engagement with the place. Ordinary things like tights, cigarettes, and cotton. Through the testimony of people I know and books I’ve read (like Carlos Casteneda), I was attracted to Oaxaca. The city – not the coast. Our whole trip was five weeks, two in Mexico City and three in Oaxaca. It was my first trip to Mexico, although I had read a lot about the country before. When we got there everything unfolded very quickly. It was amazing; we really had a great time, as you can see, such a big book from such a short trip. But actually we stacked a lot of things in.

MG: Is it a kind of chronicle of your creative process?

SL: It is about the whole thing, the making of it, the people who were involved in it. It is a storybook with pictures.

MG: Why did you choose this title?

JS: We made a Spanish word of tittipussy, by adding the Spanish “dad” particle to it.

SL: We loved the “dad” thing; it was a kind of feminine adjustment to it. In English it would be Tittipussyity.

MG: What did you do with all the artworks; did you leave them in Mexico?

SL: Some stayed there, some developed into bronze sculptures. I haven’t made this kind of characters before Mexico. It was suddenly something that happened there. The shiny gold bronze sculptures seem to me directly influenced by the Aztecs.

MG: How does this new trajectory in Mexico relate to your former works? You have often been compared to Louise Bourgeois and Eva Hesse. Do you mind?

SL: I can see what people are saying. But I’m not looking through books with Louise Bourgeois pictures. It just happens. It’s a tactile thing. We share a very “hands on” approach to manipulating materials. But we’re from different eras and different lives. In that respect I think what we are expressing is quite different.

MG: Speaking about the different angle: in 1996 you made this well-known self-portrait with two fried eggs on your breasts and a cigarette in your mouth looking very provocatively at the camera. Was this how you saw yourself back then, or how you wanted to be seen?

SL: I didn’t think about it. I was using myself as raw material. Handy at the time, since I was there and I was cheap.

MG: What about your latest portrait made in Mexico?

SL: It is me on the toilet. Julian just caught me there.

JS: We were with a lot of friends. I just went into the bathroom, had a camera with me; I saw Sarah and took the picture.

MG: You look totally happy and even a bit childlike. You must be very secure about yourself to let yourself be photographed like this.

SL: I’d just pulled my slip down, and had a lot of Mescal the moment he came. Nicole at Contemporary Fine Arts said there had been a couple of complaints on twitter. I don’t see it as offensive. I decided to put it in the show as it made a link with my first show in Berlin, Is Suicide Genetic?

MG: Let’s talk a bit about how it all started. You were one of the main representatives of Young British Artists.

SL: Not so young any longer, but still childish. [laughs]

MG: In 1987 you graduated from Goldsmiths College and 1998 you participated in the Freeze exhibition, which turned out to be one of the defining moments of contemporary art. The work that you made for Freeze was an aluminum object put on the floor but a couple of years later you made Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab, which seems like a radical change in use of materials and in the conceptual approach to art.

SL: When I was at college I didn’t really find my voice. It happened only after I left. I was actually quite disillusioned by my work at Freeze. You don’t think like that at college because you’re at college to make art. Therefore, making art is a “given” – no need for the question. Tutors are there to criticize what you do but they don’t question the fact that you made something. Out on my own, grappling with huge piles of bricks or plastic or aluminum, and filling up my tiny room with it, I began to wonder why I was doing it – what good is it to me?

MG: Were you brooding on a concept or did just started doing things because they interested you?

SL: I was looking about for something to read. I always read a lot but I’d become bored with Literature. Andrea Dworkin fell into my lap and she was very compelling.

MG: Was it a conscious decision to take the feminist position as the subject of your work?

SL: I got very interested in the idea of censorship: whether censorship is a good or a bad thing. I have never found an answer to it. In 1990 I made the show Penis Nailed to a Board. I took the title from the headline of a newspaper article about a group of men who were playing sex games, of which a part was to nail the penis/foreskin to a board. They were doing it because they liked it. The police snooped on them and they were taken to court and punished. But they were just doing it in private. They were “consenting adults.” Still, most of them received a prison sentence. The perversion of the policemen involved wasn’t mentioned. That case made me think, what is going on here? Is it a good thing to say you cannot do something? If we are surrounded by sex and violence, which we are, especially by violence in the media, it does affect people. All these thoughts made me rethink my angle. And then my works started, really.

MG: You just said that violence affects people. Does your work affect people in the same way?

SL: As people our knowledge of ourselves and the world comes completely from what is around us. We exist “in there,” not somewhere else; there is nowhere else. So, of course we’re affected by images. I’m making what I make self-consciously from inside “there”/“here.” And I am self-conscious. I think people perceive the “me” in my work – or at the very least the woman in it, and that affects their reading of it. In a gallery space they also realize this and that makes them self-conscious.

MG: For your new voice you also found new materials, everyday objects.

SL: Yes, but again, before I went to college I was always making objects by hand, that was what I liked. College was the place where you go to learn: to learn about other artists and think about sculpture, which was almost the opposite of what I was doing before.

MG: Before you went to college, were you conscious about making art or becoming an artist?

SL: No. I was just decorating my bedroom with stuff cut out of magazines and making mobiles out of coke cans and suchlike. Creating an environment for me and my friends.

But when I look back I can see how everything somehow fits together, comes back if relevant.

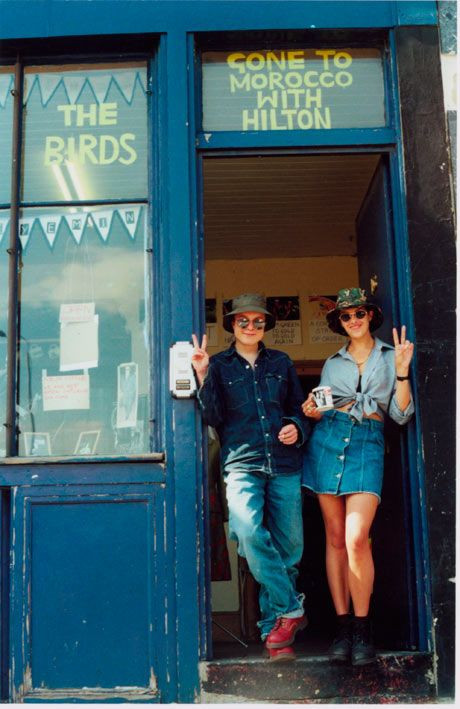

MG: So, after college you found your language and started The Shop together with Tracy Emin. Did you have an artistic concept for this or did it just happen?

SL: We had a shop rather than a studio. I didn’t have my own studio at the time – I was sharing one with Gary (Hume), my boyfriend at that time. Tracy and I just became friends. I thought: I don’t want to go to the studio, it’s so boring. The Shop was not like a big concept but we did some concepts within it. At the time, nobody had a mobile phone so we didn’t know what would happen really.

MG: Did you sense somehow that this could be a project with big artistic potential?

SL: We did. Although it was strange, it only lasted six months. During these six months I got to know so many people! They came through the door because we had The Shop. And then we realized how big the scene really was.

MG: Did it help to create this idea of togetherness, which in turn was important to create the image of YBA?

SL: Before the nineties the contemporary art scene was limited to a few galleries. These galleries would take on a new artist once a year or so. They had the authority – and they could be quite stuffy with it. In the nineties – and The Shop was a part of this – a bunch of artists emerging from colleges began organizing their own exhibitions in abandoned buildings. More and more artists started turning up to see them. Eventually we started to get beer sponsorship, and this helped. It was a buoyant scene kept up by the enthusiasm of many young people. We were our own audience. From that new galleries emerged – Sadie Coles, Jay Joplin, many others. It was a revolution.

MG: At the time Europe was in a heavy economic crisis, the art market for contemporary art in Europe hardly existed, and the network of commercial galleries was missing. Despite this situation you started, in a very short space of time, to work with new galleries and established ones. You joined Barbara Gladstone in New York, Contemporary Fine Arts in Berlin, Sadie Coles when she started in London. Why were you so interesting to the galleries?

SL: I did a couple of projects at Anthony d’Offay under the auspices of Sadie Coles. I didn’t know then that she would one day have her own gallery. I did a show with Jay Joplin at his original White Cube. Various exhibitions in alternative spaces. I also showed the work of Gary Hume and Angus Fairhurst in my bedsit and invited our friends along. I suppose I was quite active.

MG: How come Barbara Gladstone found you?

SL: Barbara invited Gary to do a project in her summer project space in Rome in 1990 and we went there for three months. I went along as Gary’s girlfriend. And that was when I first met Barbara. Apparently, she was quite impressed by something I said at table one night.

MG: What did you say?

SL: We had dinner: Barbara, Gary, me, and Mario Merz. Mario asked me why I wasn’t talking. I said, “When I’ve got a platform, I’ll talk.” Barbara liked it.

MG: Do you think that your feminist position has helped you?

SL: Yes. The galleries that existed at that time – Lisson, Karsten Schubert, Antony d’Offay – were only taking in the men. Suddenly there was a great liberation of women artists: me, Tracy Emin, Gillian Wearing, Anya Gallaccio. We suddenly came out and became visible.

MG: Has being a woman also helped in the reception of your work? If Wanking Machine or a work like Au Naturel would have been made by a man they would have been called sexist and macho. In your case they are a feministic critique.

SL: Sure. That was very much in my favor but that was at the same time what was so funny about it.

MG: Your approach to and use of materials has been very exciting. Have you always had this sensibility for materials?

SL: I think I have. I remember, as a child I used to unpick wool, I always liked texture.

MG: There is also a certain truthfulness to objects and characters in your work. A melon is a melon before it becomes a breast; a cigarette is a cigarette before it signifies death. Is this how you want to treat materials?

SL: Yes. I’ve tried sometimes to be dishonest, but I can’t live with it. Not because it’s dishonest but because it looks wrong, it has to be natural.

MG: A very good example of staying true is your urinal artwork that did functioned as a normal urinal. Was it a competition with Duchamp?

SL: Not really. You cannot say this was the idea, in the same way as you cannot say it has nothing to do with him. He is there. So it would make a difference for this work, but it is only one difference. I’ve made toilets so many times now.

MG: Why are you so fascinated by toilets?

SL: I’m not sure. I think that must be something that happened before I was really conscious.

MG: Is this something British?

SL: Maybe. I don’t really know. But it suddenly struck me. I didn’t set out to make autobiographical work. Quite the contrary. Nevertheless it becomes a biography of sorts – looking back on it. And looking back it also seems more personal to me than I imagined it was.

MG: I read the book about YBA written by Gregor Muir; there was so much drink and drugs all the time, how did you survive it?

SL: I don’t know. Eventually there came a point that I moved out from London. Just to calm down a bit. But it was really good fun and I loved it!

MG: It was like you were rolling from one party into another.

SL: It was like that.

MG: When did you find time to make art?

SL: I have never had a proper studio. I’m generally still making work on the hop. I’m surprised myself how much I’ve made in this way. Also quite proud of it. Making work in the situation keeps it close to my life. I never wanted it to be a job.

MG: Is your house then full of all kinds of materials?

SL: You would be surprised; there is nothing to see. It is a mystery, but I have always managed to get everything done. A lot of what I make is quite immediate, quite ready. It is always like a thought process but it can be instant.

MG: How do you work with bronze?

SL: That is quite different thing. I cannot do it at home and I work at a foundry.

MG: Saatchi bought the urinal. Was he important for the development of your career?

SL: I think he was. The first piece of mine he bought was Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab. I had an exhibition in a tiny little shop, where, by the way, Sadie’s gallery now is. He just drove up in his jaguar or something, came in and said, “I’ll buy it.” I was eating a donut at that moment and jam dropped out of my mouth. [laughs] I wasn’t one of the people, though, where he bought everything they did. Fortunately.

MG: I can imagine that at the beginning of your career it was not easy to sell your work with its explicit kind of vulgar sexual connotations.

SL: True, they are not something that you want to have in your house. But I was also always making easier things. I don’t think that I was thinking about selling anyway. The things just happened.

MG: Did you sense that you and your peer artists were doing something different?

SL: Sort of. Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab was a breakthrough moment. I was only frying eggs everyday while the exhibition was on. It wasn’t difficult. I suppose it became a bit of a performance. Using these materials and actually cooking on site seemed radical at the time. We were definitely doing what was not there. But I don’t know whether anyone of us has expected what happened.

MG: You also met Jeff Koons. Was he an inspiration to you?

SL: When I was in college, Saatchi organized a show that included Koons and some other Americans from New York, and which influenced Goldsmith students immensely. He made banality look so yummy.

MG: Was art history important to you?

SL: Not massively important. The first artist I liked was probably Eva Hesse because of the texture of her work and the textiles she used. And there was Jeff Koons’s stuff and later on I got much more interested in British artists like Gilbert and George. More recently I became good friends with the late Franz West. Influences come and go. I think that a lot of influences are unconscious anyway.

MG: Can you imagine what your unconscious influences would be?

SL: Well, I could speculate about it. Maybe my subconscious is influenced by Louise Bourgeois. I don’t know. I’m obviously responding like everybody else to the times I live in and my surroundings. You’re made up by them, you cannot escape it.

You can’t get any distance to it either. I can’t get away to have a look at myself.

MG: Is being British an important part of you?

SL: I can’t take it out of me – any more than being a woman.

MG: Have you thought about your sense of humor as British?

SL: It’s only since I started doing so much travelling that I started to understand what people mean by it. You take so much for granted; you don’t have any objectivity towards it. My works are based in real life. Funny, but also sad; very human in a way.

MG: Did you consider the work ‘Au Naturel’ a bit of a joke?

SL: Yes, I made it in Germany for a show at Portikus in Frankfurt curated by Georg Herold, another artist I like very much. Some of the artists were students from the Städelschule, the other part was English and we made what was called “Football Karaoke.” The English were driving from England in a van to Frankfurt. Some of us brought works with them, I didn’t. I went to a second-hand shop and I made Au Naturel and Bitch for that show. A lot of my artworks have been made in quite low-key circumstances. I don’t have to be too overly self-conscious, too planned. I can just risk it because it is fun doing a show and doing it with friends. That sort of working environment suits me very well, which means I don’t have to overthink. What I like about making objects is not to have to think too much but just do. Of course there is a lot you can think about, some sort of awareness of people and surroundings. But it is quite fluid for me; the thinking comes later.

MG: It seems that you are not afraid of how people look at you.

SL: I am sometimes. But I stopped bothering about that. I have some very self-conscious moments. I remember one time that I was invited to Rotterdam to have one of my first museum shows in Museum Boijmans. I was setting up the works all on my own in this empty museum. Suddenly a whole bunch of local pensioners were standing behind me while I was adjusting a couple of breast melons and then I thought, you can get me sometimes. I have some moments of embarrassment.

MG: Do you intend to provoke?

SL: I think so. It is not so much about other people but about myself, finding some sort of edge. What people think about me and know about me is much less than I actually do, but it is everything people talk about. I can live with that. I’m not trying to be nasty to anybody.

MG: You are now a famous artist. Has this changed anything for you?

SL: Got a bigger house . . . I don’t know, I sometimes think about it. Change is a good thing. I must have changed but I don’t think that I have changed so much either.

MG: Do you use your popularity? For example Damian Hirst has been using his public persona as a part of his artistic strategy.

SL: These days it seems to matter. For example when I did the self-portrait, I had no idea that anybody would be interested in it. It was quite a surprise to me that there was something to it. After a while I stopped doing it because the kind of interest people tend to have in an artist is quite lewd, like a cult personality. And I’m not so interested in that. Sometimes I like it though and I think this is definitely worth it for me.

MG: What about your family? Are they startled that you have become such a well-known artist?

SL: They are pleased and I supposed proud, but we don’t discuss it.

MG: Did they support your artistic path?

SL: They did, although they were not particularly interested in art. I did not go to galleries when I was young. I went to museums only a couple of times.

MG: Did they find it strange when you decided to go to the art school?

SL: I was always a bit weird, so nothing was strange. For a long time I was the poor relative in the family: if this is what she likes it’s okay, but the price for this is that she is poor. When that changed that was a weird moment.

MG: You were born and lived for quite a long time in London.

SL: I never imagined that I could have a life somewhere else. I still have a house in London but now most of the time I live on the countryside. It started as a weekend place with Sadie Coles, but then I stayed there more and more, and we bought a house so I could live there permanently. It helps me to get out of the craziness, because London gets really crazy. And I’m sort of addicted to it.

MG: What about the current nomadic condition of the artist?

SL: I like to travel for work but I don’t travel a lot for pleasure. I like to have a reason to be somewhere. It is a different way of engaging, even getting materials and trying to get things. You have to make adjustments, the things like toilets are different everywhere. Even blocks – nowhere in the world do you have the same blocks, which is okay; you just have to adapt your ideas and then different things happen. I’m still expanding my use of materials.

MG: Do you often cooperate with other artists?

SL: Because Julian and I live together it is just the way between us. We do a lot of things together because we always liked that. I also liked doing projects with Tracey and shows with Damian and Angus. Making art is just a part of my normal life and normal friendships. It is a lifestyle.

MG: So, for you art is a way of living?

SL: Yes. That is my alternative to not having a studio. Actually this is just a part of my life.

MG: Have you ever thought about art as your profession?

SL: Never. Back than, when I was doing what I liked without having any money I thought that’s how it would be. I didn’t mind.

MG: Would you mind now?

SL: I didn’t mind then. I couldn’t give a shit about money, about having a washing machine or a house. I lived in a squat for three years; I just wanted to have freedom.

MG: Do you experience now that it is money that gives you freedom?

SL: Yes, I don’t have to worry but I’m not very grand with buying designers etc. I spend a lot of money on eating and drinking and stuff like that.

MG: Do you buy art yourself?

SL: No, mainly because I can’t look after things. My house is like my studio so it is a great risk to put something there. I do have works by my friends, which we exchanged.

MG: Do you look a lot at art? Do you visit galleries?

SL: Not so much any longer. I used to do it a lot through the nineties, in Germany and New York. I’m not looking for something in the same way that I was looking back then, looking for a clue: what is art, what is good, what do I like. It might start again.

MG: is there anything that can give you the excitement of the new?

SL: I don’t know, I was always reading books. All sorts of books: novels, a bit of philosophy, I like music a lot. Julian makes really nice music. It’s about immersing myself in a certain sort of atmosphere.

MG: You had a retrospective in Whitechapel last year that was extremely well received.

SL: It was quite absurd. I stuffed really a lot in. There are so many shows that are so minimal. I just thought if you have a retrospective just get it all in. It was really fun.

MG: How was it for you to have a retrospective?

SL: It was a bit weird and melancholic seeing all these things together. I treated the way of hanging as a whole artwork and the hanging was completely fresh.

MG: Did you discover anything new about yourself looking back from your perspective today?

SL: How well all these things work together. There are a lot of different materials, different approaches, but they were all happy together, which is nice. Where does it all come from? Even the radical works, when you look back they just seem very harmonious and continuous. And this was a surprise. Because you never know what you are doing.