Robin Rhode

Published: November, 2011, ZOO MAGAZINE #33

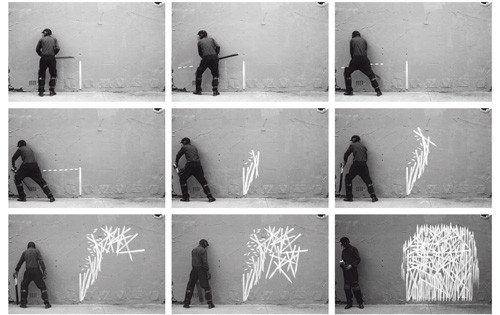

South-African artist Robin Rhode conquers the art world with his highly aesthetic, intense and technically superb photographic works and film animations.

Marta Gnyp: What is extremely present in your works is the sense of order. There is always a structure you can sense, a repetition, a rhythm and clarity about the composition and forms.

Robin Rhode: I am absolutely conscious about this sense of order in my works and my formalistic approach. This goes back to various influences to me as a young artist. I was the only student in our South African art school interested in minimalism that I was researching extensively. I was trying to find a way to order the outside reality because Johannesburg is so overwhelming, complicated, politically charged and dangerous. I wanted to find some kind of structure to it or some kind of reductive approach in order to control the chaos, to find an expressive nature inherent to all of us. I wanted to use the structure of Donald Judd or Carl Andre as a structure element into which I would be able to pour my reality.

MG: Coming from such an over-politicized landscape, it had to be a very conscious decision not to make politically-engaged art but to make highly aesthetic works. You are a bit of an outsider in comparison with other contemporary artists from your generation who embraced malformation, destruction and deconstruction as a dominant approach. You seem to use a completely different formal language.

RR: A lot of artists today use the notion of non-monumental, anti-aesthetic approach. I came from a very anarchistic and charged place so I wanted to bring this strong emotional experience of the social chaos and political turmoil, this notion of identity to one formal element that can embody this whole meaning of the personal experience. How can I represent it with the simplicity of the material and signify and encapsulate this universe? This is something which not only applies to my work but I could see it in minimalism as well. You look at the work of art but at the same time the artist depicted the world around you.

MG: You escaped the extremely rough and complicated situation through your formal language and also by creating special characters in your works. Your protagonists seem to be universal and timeless. You refer to archetypical dreams, hopes and fears of the human being. The objects you make are often like a platonic idea of an object. For example, the pristine white chalk bicycle. It looks like you escaped to relate your works to real space and real time.

RR: I don’t begin a work of art with a universal frame. I have a basic idea and this idea asks me a set of rules. A man ice skating on the concrete is about a game, an activity that is playful, absurd and funny at the same time. Somewhere in the world, in South Africa, I want this guy to skate on the concrete down the street. It creates even more humor because people don’t skate there at all. Then it becomes even more obscure and absurd. I have always a geographical place in my mind, playing a fluid scenario, trying to create a situation which is completely open, which could be any concrete yard in the world without geopolitics.

MG: Are you not irritated when the public and art critics claim your art for political purposes?

RR: Not at all. Your responsibility as artist is to create and then the audience takes the responsibility to interpret. They have to make the sense of the world to themselves. You cannot control it.

MG: Speaking about the protagonists in your series, in your early works there was this young street boy. Since then a businessman has appeared. The businessman, who could be the symbol of the fake rationality and control, replaced the playful experimental boy.

RR: Yes, the businessman represents rational emotionality and the administrative aspect whereby the street boy has the opposite anarchistic character. But there are other elements as well. The businessman relates to the fictional character from a book called Momo in which the uniformed men are stealing the time by forcing people to think only of work, money and ‘saving’ time. The suit makes the male look like a gray uniform. My childhood and my school were also influenced by the uniform. It represents the sense of order.

MG: The sense of order is the key word to understand you.

RR: At the same time it forms the context for performativity. The performance shutters the order and adds other elements to it.

MG: In your performances, you play quite a different character. I saw you in a gallery space recently making a performance. You were acting like an uncontrolled unpredictable aggressive missile, clashing your body against the bodies of the audience.

RR: I love life performances. Even though in my animation films there are many performative elements. The real performance is something different, more intense when people are laughing and making comments. Having done life performances for many years, I have developed the intuitive skills how to deal with the public. My artistic work started with performances.

MG: Why? Did you want to experience a direct and immediate reaction from your audience?

RR: I just found that the gallery or museum experience was too passive. I thought, ‘wait a minute, you are attending the opening drinking a glass of wine and having a conversation, I demand your attention. You need to pay attention to me because I’m giving you now the maximum of myself.’

MG: You don’t mind how they react?

RR: Sometimes when I’m in the moment, I don’t even notice how they react. I like to know how it was for them afterwards. In the moment I’m trying to charge the space physically so much that they almost feel the fear inside them which is the same fear that I probably experience in confrontation with them. In the moment of the performance, I’m anxious to claim the space. But I’m taking a position between them in order to create a drawing, to make this particular mark and to convey it to the audience in the space which is full of sculptured energy and physical intensity.

MG: What was your most intensive experience so far?

RR: Performances are always different and special. The most funny was probably the performance in the MusŽe d’Art Moderne in Paris in 2005 in a group show about wall drawings when I managed to engage the audience to play with an imaginary rope. They were all jumping with me and laughing. When I disappeared they were still jumping. When they applauded, they applauded to themselves while I was catching the breath in a corner of the museum. There was so much humor involved in this piece. But I’m putting myself in the physically intense bodily situation in order to draw a particular mark.

MG: Performance as an extension of your drawing?

RR: Yes. To create a drawing is about taking us in the future. The drawing is so defined, so stylistic. It is the basic. The first line towards the sculpture and the painting. How can we take it further? Where can I take it? So I’m going through processes of catharses doing performances to feel this mark. Sometimes after a performance, I wish I could draw like this in the studio without forcing myself into a performance without becoming anxious.

MG: You have a special relationship with the drawing.

RR: I have a big issue with the drawing. I have a problem with the scale and I have an issue with attention in my studio.

MG: During the performance, all happens spontaneously while there is no necessity to draw in the studio?

RR: Exactly. When I work in my studio I struggle because I need the same intensity as during the performance. Curators have often asked me to exhibit my drawings. But to create a drawing without physical necessity, without a performative idea, without the audience watching me, in a blank and controlled studio situation is difficult. In the studio, I have a piece of paper, no audience and unlimited time. The drawings in performances are related to a particular sense of time. I want to create a drawing that is able to embody the same energy as during the performance that you not only see the line but capture the intensity. This is my next step.

MG: Let’s go back to your earlier artistic life. You started with performances but you were called the artist already in the primary school.

RR: Yes, already than I felt my responsibility to make art. I put my name on the toilet walls or other walls at school.

MG: When did you discover that you can draw?

RR: Very early. When I was a child I was very shy and very anxious, also quite small and skinny, always in the background. Then through my puberty and adolescence this desire to draw became even stronger because I became more an individual. It gave me confidence in the group at school. I became the school artist. I could belong to the core group of the pupils. It gave me a status in the school and the idea that I meant something to this sub-cultural system. We would draw a candle in the toilets and the others had to blow it off. I did the drawings but it was a part of an old subculture.

MG: And then you went to an art school.

RR: Then I was really struggling to fit into the institution. I wasn’t used to this amount of freedom we had at the art school. The drawing classes were like 6 hours, drawing a nude. I couldn’t understand this kind of freedom because I have never had it before. I spent most of my time outside with the guys on the street. I was an absolute nightmare student.

MG: But they knew you were extremely talented.

RR: Yes. But the first year, I failed completely. I was the worst student. I couldn’t find a way to discipline myself, to make simple brushstrokes during painting lessons. I didn’t know what to do. Secretly, after hours when everybody left, I worked alone in other parts of the campus and then I would make videos filming myself doing a piece.

MG: Were you rebellious towards other students?

RR: I rejected them completely. I didn’t know how to share the studio with the other students. It was stupid. They had a very strong sense of craftsmanship and materials whereas I failed because I didn’t have enough respect for the material. Even today I have a problem to respect the material.

MG: Although you are a perfectionist regarding the technical side of your work.

RR: It took me a long time. I used one material and went to another one without paying attention.

MG: So what happened then to you? You were in a deep crisis?

RR: I produced works outside and bring those in the studio. I made a sculpture of a barcode using the minimalistic forms and then I decided to make molds of different bar codes in soil. Then I added interactive performances. The big trigger was the video-making: I put a cheap video camera on a simple tripod, pressed ‘record’, acted into the frame and just drew in front of the camera. And then I had the monitor playing the video back. I gained so much power and confidence from that. That was really true for me because this form of art-making was very personal. My practice is not based on concepts and theories. In contrasts to many artists who base their whole practice on range of theories, my art is for me coming from something which is really true and unique for myself. That gives me a lot of strength. Even if I’m in a situation with my back against the wall, that I don’t have any ideas, just give me piece of chalk and I’m going to do something with it.

MG: Although your art is not built up on a specific concept, do you see your art as a continuation of specific artistic traditions?

RR: Absolutely and I even more like to be a part of the tradition because I can also deliver critique. I like to somehow compare my works to other works and movements. I use a lot of black and white photography to position myself versus the photography in the 50s and 60s and re-contextualizing it. During my study, Kendell Geers struck me a lot because when I was struggling to find my own way, he showed objects I could really relate to. I saw the work of Geers in Flash Art. As a student I was reading all available international art magazines to know exactly what was happening outside in the world, in France, Italy and the USA.

MG: It is interesting that a South African artist struck you so much.

RR: I saw this South African artist working in the international situation and I loved it. He simply isolated an object—a bottle of beer. At that time, my professors at art school, also artists, spoke about different themes like the religion, the church, the architecture, South Africa. I was curious what are other artists doing outside? I wanted to become a part of the world. To show people from this place that we can mean something. This became my mission. I was very motivated to convince people to take me seriously. I’m still very committed to my art and very serious about it.

MG: When did you have the feeling for the first time that people took you seriously as artist?

RR: When I completed my study. I got distinctions for a lot of subjects and had great results at the end. Comparing with my artist students, I took art completely seriously. Most of them went into the corporate world after the graduation. They accepted that the only way to survive in the society is to have a ‘real’ job like marketing or accounting when you will be wearing this gray suit. Then you are serious and able to survive. Everybody whom I knew believed that being an artist in South Africa is impossible to survive. I was determined to convince everybody.

MG: How did you do it?

RR: I went to exhibitions and I was explaining what I’m doing. It was like a permanent artist talk. Then I would be doing a performance.

MG: Did you never think that you are doing it for people who don’t understand you?

RR: No. I invited different people to the gallery to show that this is important. Museum people but also my neighbors who saw me making graffiti on the walls at the corner of the street who thought this is guy is a looser. I showed them that this graffiti on the street corner was like a research that I needed to become a part of the space. To be totally open to absorb the situation, I used to walk for hours through the most dangerous parts of the city just to absorb it.

MG: What did you want to absorb?

RR: Fears and emotions. The way things are happening. I was hungry for any single action.

MG: What do you do with these experiences?

RR: Certain ideas gained from some particular situations I saw appear in my art, directly or much later. I would walk into this part of the city and see what is going on and see this guy throwing the dice. I would stand there and look just to check it up. Years later, I would make a photo series about throwing dice. Now I live in Berlin but when I’m in Johannesburg, I would go again and walk anonymously through the city to discover it again and to refill myself.

MG: When did you leave Johannesburg?

RR: In 2001, I came to Berlin. My career was taking off. I got a residency in Berlin and afterwards in London. I had a small group show in the US with very interesting artists. A lot was happening and I decided to stay in Berlin.

MG: Could you easily get used to Berlin?

RR: There are amazing moments that I experienced here, especially in the museums. The city has a very lively art scene although I don’t go out to the openings very often. It is a bit too homogenous to me. Things just happen in Berlin. There is nothing dramatic. Cutting edge is about fear that defines life.

MG: Do you intend to stay in Berlin?

RR: I will stay in Berlin because I’m very committed to this city also through my family. I recently bought a very interesting studio space. I would like to spend more time in South Africa. Maybe a couple of months in Johannesburg and couple of months here because I also want to contribute to the situation there. Robin Rhode is represented by Galleria Tucci Russo (Turin) and White Cube (London).