Mary Corse

Published: June, 2018, Marta Gnyp in her book "YOU, ME AND ART", 2018

Marta Gnyp: You must be extremely busy at the moment! As we speak you are preparing two important institutional exhibitions, one at Dia:Beacon opening in May and your survey at the Whitney Museum in New York opening in June.

Mary Corse: Yes, actually there are three exhibitions. Another reason why I’m so busy is because I also have a show in London in May. The months before a show can be quite intense for an artist.

MG: Are you creating new works for them?

MC: Yes. That´s why I have a good excuse to spend a lot of time painting. I paint, paint, and paint. I like painting. You’d think I’d be sick of it by now, but it’s still very freeing.

MG: The Whitney survey attempts to show the development of your whole oeuvre. What about Dia: Beacon. Will they focus on a specific part of your work?

MC: The Whitney exhibition starts with early work and it goes to the present. The Dia: Beacon show mostly focuses on early work, with one recent painting. They will have the first light paintings and an early electric light piece. There is a good balance between the shows, and you get of what I was focused on then, and how one idea led to the next.

MG: Are you very productive? Do you paint quickly, or is it a complicated creative process?

MC: Well, my works are very detailed so it takes a lot of time to make them.

MG: Why is the process so important for you?

MC: Well, painting gives me a deeper connection. As soon as a paint brush is in my hand and I´m painting, it becomes a different conversation rather than our daily thinking and judgments. The concern about what´s going on in the world disappears and it all becomes about a different conversation, a conversation with abstraction.

MG: What does this conversation with abstraction offer you?

MC: I find it very satisfying for my psyche, and exciting. The act of painting has the ability to really transcend your moment and put you in a different sphere. Obviously, it does that for me. I consider that sanity when searching for meaning. We need meaning which is consciousness. And I find it there in painting. I find the infinite conversation instead of finite thinking.

MG: Did you have this deep relationship to painting from the very start? I read that you were exposed to culture in a broad sense already in your childhood. You started classical piano lessons at the age of five, followed by jazz and ballet. Was visual art a part of your education as well?

MC: I started painting early and I´ve always used it as a place I could go. As a nine-year-old I was drawing the human figure realistically. Then, in the seventh, eighth, and ninth grade I had a fantastic instructor at the school in Berkeley that I attended. Her lessons gave me a kick-start into Abstract Expressionism.

MG: Have you always been interested in abstraction? Figurative painting never really engaged you much?

MC: I am interested in abstraction but I´m actually sort of a realist. I’m interested in making a painting that makes you feel some kind of truth about our human state and where we are on the planet. We live in abstraction. You don´t see the other side of the moon. You don´t see the room behind you. But they’re still there. And that’s why abstraction has interested me from an early age. It is about the truth. I want truth to be in the painting along with other things are ambiguity, space, and time. Time is an important part of my work. That´s why I make them so wide– so that it takes time to walk across them.

MG: The process seems to be as important to you as the final result.

MC: Oh yes. I like making things. I like doing things and making things happen. I like discovering things and research. . In the ‘70s I was designing this really big earth kiln to make an eight-foot ceramic tile. All the kiln builders told me, “Oh, it’ll never work.” But I kept going until I found something that did. The same thing happened when I made my wireless electric light pieces in the late ‘60s – the ones with the generator hidden in the wall. For those, I was building my own generators. [chuckles] I love the process.

MG: The act of creation…

MC: I love to use my hands to make things. Out of what? Out of the abstract forces. You try to make something that has meaning out there, where things appear meaningless or questionable.

MG: Let’s go back to your fascination with abstraction. When you were getting your MFA in the mid-1960s, Abstract Expressionism was kind of dying of out.

MC: Well, I actually started with Abstract Expressionism when I was about twelve at private grade school. This was in the mid-1950s when Abstract Expressionism was very strong. Jackson Pollock was still painting. By the ’60s, I was leaving it.

MG: I read that in 1964 you made this abstract blue and red painting that became very important to you because you got abstraction involved with light.

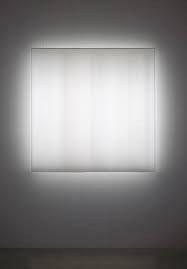

MC: Yes, I was starting down my own path. It´s funny, it´s like the paintings tell me what to do. You have to be able to have that abstract conversation. The paintings would say, “Oh, I need this,” “a little bit here,” “a little bit there.” After studying Josef Albers, Hans Hoffman, and mostly Willem de Kooning for a few years, the paintings started telling me other things. I started doing my own, and the first one of these was the red and blue painting. The most interesting thing about this particular painting to me was the flash of light between the red and the blue. Through the painting, I saw how opposites can work and that certainly made me see light in the painting for the first time. Next, I used silver flakes and colors in my paintings and then, when I started painting with the white, that was really about light too. The white turned into light.

MG: Has this reduction process required extreme discipline? To concentrate on a very limited palette of colors?

MC: When it comes to making paintings I always think of it as a passion. No, you don´t have to be disciplined to go minimal. It feels great to get rid of things, to get rid of your ego and your hang-ups. I used to sand the brushstroke out because I wanted to get rid of subjectivity. I didn’t want any artist´s ego, nor any signature.

MG: This phase didn’t last very long though and you went back to subjectivity. There is a brushstroke in your paintings.

MC: There is, yes. I put the brushstroke back into the painting in the late ‘60s. I was very young when I was making those first flat white paintings, twenty-two or twenty-three. Then I went from white into the white light and from there to the wireless flat electric light boxes. In order to build the bigger wireless high-frequency ones I had to get the materials from Edmund Scientific, and they wouldn´t sell the parts to you unless you´d passed a certain test, so I had to go and learn about physics. When I was there I got interested in quantum physics, and that triggered some kind of an amalgamation in my brain that kept changing and changing. I´m still fascinated by it, realizing what a perceptual reality we are living in. Before physics, I was looking for a truth out there, an objective truth. Afterward, I understood that perception creates reality so I put subjectivity, the brushstroke, back in the painting.

MG: Searching for the truth sounds like a philosophical goal.

MC: Well, for me, that’s what art is for. We’re not going to be searching for a lie. The idea is to get rid of delusion or to experience the feeling of truth. What else is art about?

MG: On the one hand you are searching for the hardly-graspable truth, on the other you are fascinated by the physics based on the concrete facts and which therefore limits what can be known.

MC: Physics has become metaphysicis – facts are not so concrete. I always said, artists and physicists are the opposite sides of the brain – put them together sometimes. It´s part of our human state to have both kinds of thinking. We have logic and thinking, which in my opinion doesn’t go as far because they’re finite. They’re the past. To me, the other side – intuition, without thought – is where art comes from.

MG: You are using a very unconventional material, glass microspheres, to paint. Did you discover the microspheres in an intuitive way?

MC: Well, after I had made those Plexiglas light pieces in the ‘60s, I wanted to find a way to put light in the painting. Painting, to me, has never been about the paint, but what the painting can make you feel. When I realized that perception was so much a part of reality, I wanted to put it back it in the painting. I wanted to have the brushstroke but I also wanted to keep the light. So, I went around trying to find out how I could put the light in the painting. I would try different materials, such as Murano paint, stuff that glows in the dark, and all kinds of different things. And then I saw the paint on the highways. I was driving down the road when the white dividing line lit up and I thought, “Oh, let´s try that.” What I like about this material is that it changes with your perception. It is not reflective – reflective is one–two. A microsphere is a prism – one–two–three; it creates a triangle between the surface, the viewer, and the light source. So, as you move, the painting changes. Therefore it puts the painting – let’s say the art – into your perception rather than on the wall.

MG: Is this not slightly contradictory? You just said that the art is in the perception of the viewer,but at the same time the painting is still an autonomous object.

MC: Well, I used to think that, but not any longer. I don’t think of the painting as an object out there now. Perception is what happens inside you. The art is when you wake up to the truth of our human state.

MG: The way I understood it, painting is something that has a life of its own.

MC: Well, that’s part of the painting’s life. It talks to you and it’s in your perception. I think it’s the question of our times, even though I think that I’m the only person asking it. [chuckles] Now that we’ve realized that perception creates reality, we can do whatever we want to do. We want to go to the moon, we go to the moon. Whatever you dream up, you try. Perception can create reality. But the question is: How subjective is the universe? What is that, how much is out there, how invisible is matter really? We live in such a mystery. The reason I like both physics and art is that they’re methods of inner searching, or ways of learning and experiencing the human state in this questionable reality where we live our lives.

MG: Do you think that art has the ability to make something visible that is invisible normally?

MC: I do. It’s invisible until you make it visible. [chuckles] But art can talk about invisible things. That’s why I’m not really interested in making a picture of something “out there.” You want to make something that comes about from “in here”.

MG: Is your career, or to put it differently, your life as an artist, exactly what you wanted to do?

MC: I never thought of my life as an artist as a career, for one thing. We didn’t think of art as a career. I think that idea came up just twenty or thirty years ago. No, I painted because that´s what I love to do. It is satisfying to see a painting that I like. I never thought of it as a career, so I never chose it as a career.

MG: Still, are you enjoying what’s happening to you now? The international recognition you are receiving, different museums queuing for exhibitions of your work?

MC: Oh, yes. I feel very lucky that I have something that I love to do and it is being appreciated. Things are moving forward.

MG: You’ve often been associated with the Light and Space movement, which, as I’ve understood it, you don’t consider to be entirely correct?

MC: Well, for one thing, it should be light, space and time. It’s a big question. My art is more about the inner environment.

MG: We were talking about you as an artist. Have you even considered yourself a woman artist?

MC: I never thought of art as a gender thing.

MG: You must have been quite special, making generators and doing things that maybe at that time were not so usual for women.

MC: I never thought about that. There must be more women who were figuring out how to do it themselves. I’ve always felt very feminine and I think I am very feminine. There’s no reason that would prevent me, or anyone else, from creating what I wanted. I was a single mom who raised two kids. At that time, how many women artists did that!

MG: Which was probably not that easy.

MC: It wasn’t easy. But what was I going to do, not raise my sons? Give up painting? [chuckles] Neither of those was going to happen. My work survived during the toughest years thanks to Richard Bellamy, and eventually things changed. Now I’m painting more than ever before.