Martin Eder

Published: August, 2014, ZOO MAGAZINE #45

Marta Gnyp: It looks like imaginary and reality meet in your mysterious studio in Berlin.

Martin Eder: It is my golden cage, or more precisely, a rusty golden cage, although I know gold never rusts. A bloody dirty rusty golden cage.

MG: Quite an exciting description that immediately triggers my imagination.

ME: It’s as with the titles of my works. A lot depends on titles. A title is like an invisible painting around a painting, like an aura of meaning. Let’s look at this seemingly old-fashioned painting of a young woman. If I called it Jeanne d’Arc it would be a very boring painting. But if I called it Giant it brings new dimensions to the image because you start to question what is going on here. The painting you don’t see is more important that the one you see. If I asked you to close your eyes and imagine a painting entitled Searching for an Answer you wouldn’t by any means imagine that what I painted. Your imagination starts to work because you are most probably looking for your personal answers. I plant ideas in the mind of the viewer.

MG: Do you think that you can bring to life every painting only by giving it an exciting title?

ME: No, only my paintings. There are many paintings that are dead from the very beginning.

MG: Do you construct paintings using what you called “boredom” only to wake them up through a title?

ME: Is not really boredom but more a sense of normality. The most attractive situations in life are not when you jump out of the plane or meet a supermodel; the most attractive time in your life is when you feel that everything is fine, when you feel that you are feeling at home. What home means is, by the way, different for everybody. Home is just your title for a certain situation.

In the past I used to implant spectacular elements into my paintings. I staged surreal and frightening situations, so people could see that obviously something was strange or wrong there. After a while I drifted away from this approach because I trusted my paintings more. They don’t have to be extraordinary to be strong. It’s like seeing a black heavy-metal shirt with bones and ruptured sculls: it doesn’t look frightening at all – it just looks funny.

MG: You don’t need extraordinary settings to achieve your goals.

ME: If it is too much it becomes funny. I learned that if you go back to reality it is frightening enough. If you show people one to one what’s going on in the world, like in a mirror, it’s is even more frightening.

MG: The reality in your painting is, however, slightly different from normal; you just showed me a ‘normal’ young girl but in a harness.

ME: I obviously use my own language to render the reality, but at the moment it’s exactly the reality that is the disturbing element in my paintings. There is no such thing as normality. What you wear, what I wear, what you think is true, what I think is true – it all can be flipped by a snap of a finger into something completely different. People can change their minds very quickly. Just look at the news: man-made disasters, nonsense disasters. We act according to agreements within the group we live in and this is what we consider as normal and what we evaluate as reality.

MG: In a nutshell: you make your paintings to demonstrate how constructed reality is.

ME: Yes, that’s a part of it.

MG: Is the other part to manipulate the perception of the viewer?

ME: Of course. It’s a lot of fun. Why else would I do it?

MG: I read that you spent your childhood in a very small village and that you were brought up Catholic. How much have these symbols, myths, or narratives influenced you? How much has the idea of guilt and sin found its way into your work?

ME: I think, or I want to believe, that I’m completely free from that. We have to thank the Church for the invention of art, as we know it today. That’s the only good thing I can think of regarding the Church. If you believe in a religion that kills for its belief, why don’t you start with yourself first? Having said that, I love religions; I love the fact that people are so stupid to believe in such a naïve manner. It has all the patterns of hypnotisms.

MG: Repression of the body has played an important role in your work.

ME: Especially the female body used to be repressed by the Church. Even with the gigantic porn industry of today, the body is repressed. With the increasing access to all possible images and porn, the world is becoming prudish and prudent. People are more restrictive and private than before we had porn.

MG: Don’t you think that in the West we don’t have many problems with the body?

ME: Well, we have in America. I was asked to paint without nipples.

A young person I work with said to me: “No more nudes, nobody wants to see the nudes; in the USAnobody wants to buy naked pictures.”

MG: I can’t believe it.

ME: It seems like a new prudery is coming. I don’t care but we are facing a new wave of conservatism.

MG: I spoke about the subject of the repression of the body with someone who is a psychoanalyst. In his opinion, we are no longer as neurotic as we used to be in the time of Freud. That attention of our psychological problems now lies in the area of relationships, which we are not able to build properly.

ME: Together with the repression of the body goes in my opinion the repression of the soul. If you have a bad feeling about yourself, it causes a lot of violence towards you mentally. It is the constructed reality we live in that is very interesting to me.

MG: Did this wish to investigate and construct reality make you want to become an artist?

ME: When I was eighteen, I worked for six months in an advertising agency. After those six months I told myself that I would never ever have a boss in my life again and that I would never work for something that sells fake truths. Obviously, now I also work with constructions of truth but that’s different. I don’t want to sell cholesterol-free detergent or design political election campaigns for the left and right wings at the same time. I decided that I don’t want to be involved in business.

MG: Did you think that art is the best solution?

ME: Where I grew up, there was no art in the sense of what is understood as art and moreover I didn’t get any support when I decided that I wanted to be an artist.

MG: Do you mean that your parents weren’t happy with your decision?

ME: People tried to convinced or maybe even pressure me to join a company but it didn’t last long.

MG: Did you know at the time that you had talent?

ME: I drew a lot from when I was six years old.

MG: Then against all odds you decided to attend an art school and you went to Nürnberg.

ME: First to Nürnberg than to Kassel and then to Dresden.

MG: You started your academic education in 1986 and finished in 2001, which means that you didn’t mind spending o lot of time in art academies. Why did you need so much education?

ME: For young people, studying is often an alibi to stay off the streets. I never studied really; I just hung out and did stupid things. It was an excuse to function in society and at the same time to do what I liked to do. When someone asks you: what do you do and you say “nothing,” then you’re a bum. When you say, “I’m a student,” that’s fine.

MG: It must have been more than hanging out, because at the same time you wanted to be involved in something true.

ME: In the art schools there were many serious painters who have remained serious painters to this day. They studied with me, they are now with big galleries, but they were always humorless. They believed in what they did; even during their studies they believed that they would be the next big thing, the new Picassos. I couldn’t take it that seriously; I thought, there must be something else. If you are too serious everything becomes boring.

MG: Was it a fight against boredom that made you work in the swingers club?

ME: I did it because I needed money. I was painting bodies of other people.

MG: Did you use this time to study the human body?

ME: Perhaps. I, myself, was dressed up like a clown, being the only person who wore clothes.

MG: Was it weird?

ME: You get used to it. It quickly became a sort of ritual, so I wasn’t shocked, although I was quite young and they were quite old.

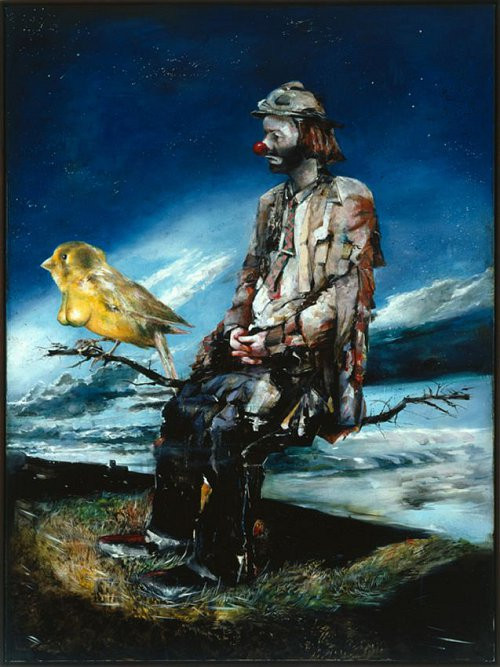

MG: I saw your painting Morgengebet with a protagonist dressed as clown who is contemplatively staring ahead. Does it refer to this period of your life?

ME: No, this is about something else. I experienced a clinical death. I was dead for about twenty-nine seconds and this was the first picture I made after I was released from the hospital.

MG: Is this is a self-portrait as a clown? Why this image?

ME: I don’t know. I’m sitting on a bench or a twig, which is floating in the air; it is more like a dream. I don’t know what it means, but I dreamed that a breasted bird was sitting next to me in the hospital. It was very personal and urgent to make it.

MG: Do you still have the painting?

ME: Unfortunately not – it’s in the Denver Art Museum. At least it’s hung on a wall and not in storage.

MG: Could you tell me how you experienced your clinical death? For most of us this is an unconceivable experience.

ME: It was quite an interesting experience, although I wouldn’t recommend it to anybody. I needed an examination of my heart muscle and this was planned for 7 p.m. at the clinic. They pull a big string through your stomach into your heart. On the way to the operating room, I saw an announcement in the lift that there would be an electricity test at 8 p.m., which also mentioned that, in case of emergency, there is an additional generator that could be used. When I got to the operating room at seven, I asked the doctor whether this wasn’t too late, but he said that it would only take ten minutes. I didn’t get an anesthetic because they want you to be awake. They put six strings into me but then something went wrong, they were pulling it out and back in my body. I could see this big clock on the wall ticking. At ten to eight the doctor said: just one more string and we are done. But then the phone started ringing in the room next door and the chief surgeon said that we had to stop now. They tried to pull the strings out but probably they somehow created a vacuum so my heart started to panic with a heart rate like 180 beats, which means that the heart muscle got completely out of control. I could see everything on the monitor, also that my heartbeat became a flat line quickly afterwards. My heart stopped. Everybody was looking panicked and then the lights went out in the whole room, so the monitors and all systems were cut off. Then the emergency generator switched on and all instruments restarted but very slowly.

MG: Were you aware all the time?

ME: Yes. I even tried to communicate, which was impossible. In the meantime they applied a kind of electroshock machine on batteries to reanimate me.

MG: Has this experience brought you even closer to your study of consciousness and the subconscious, also for your art?

ME: Definitely. I have attended many seminars and classes on this subject. I went to hypnotherapy schools and I even have a diploma as a hypnotherapist. Although at first sight hypnotherapy doesn’t have anything to do with art, the more deeply I got into the subject the more I found that there is no big difference between them. Because they both deal mainly with the subconscious.

MG: Are you attempting to reach the subconscious of the viewer?

ME: When I paint I’m trying to find symbols that are very easy to understand. Kittens, naked asses, faces – these are symbols which we learn to interpret very early. It’s very hard not to find a little dog very cute, even if you are very well educated and ironic; at first you will always fall into this image, because it is anchored in a positive feeling. It is a fact that our subconscious is very powerful. People who have been to hypnotherapy sessions with me could do a lot of things that they cannot do when they are fully awake. They were completely surprised. The good thing about it is that if you show it to the people they become very empowered: if I can do it now I can do it outside the therapist’s room and I can change my life.

MG: Do you practice hypnotherapy a lot?

ME: Sporadically. I can make friends quit smoking but I don’t have a sign at the door advertising my hypnotherapy practice.

MG: Do you exercise hypnotherapy on yourself?

ME: Certainly.

MG: Is this not contradictory? If I understand it correctly – although I’m completely ignorant in this field – you create an access to your subconscious, which means that you lose control of yourself.

ME: You never lose control of yourself; on the contrary, you gain more control. If you train enough you can even control your heartbeat or your breath. I can affect my heartbeat a bit or change the temperature of my fingers. During hypnosis you are fully aware of what you are doing, but you do it on a different level. You clear your mind. It is not even meditation because during meditation you are trying to think nothing, to empty yourself. During hypnosis you just try to stop your conscious brain talking to you and it gives up.

MG: How are your experiences with subconscious mirrored in your paintings?

ME: Through pattern interruptions. We have daily rituals that we repeat thousands of times without being aware of them. If, instead of just shaking your hand, I would keep your hand in my hand for a longer period of time you wouldn’t know what to think. I wouldn’t be doing any harm, but I would be interrupting a pattern. In this instant, your subconscious mind opens a bit. In these seconds, you are highly suggestible.

MG: Because I’m out of balance.

ME: Exactly. Let’s now go to pattern interruption and paintings. Let’s have a look at this flower painting: you could think about something sexual as it renders an exciting hole, in the middle of the flower body. But there is more, the flower is very large. What does it mean to you as a viewer: am I a bug or a fly? It reduces you. Then you look at the title and it’s not called Red Flower but Tunnel and then you think: “a tunnel?!” You start to think. It is a riddle. A good painting should be a riddle. It is very important to have a secret in an artwork.

MG: If your art is criticized, it is for being kitsch. Is kitsch a part of the strategy to address the collective subconscious?

ME: Absolutely. Kitsch is nothing other than a compression of feelings. A compression of feelings is a tactic to survive. Sucking on the breast of your mother is a compression of feelings and this we will never lose. This is why some people smoke. Compressed feelings and attitudes reach more people.

MG: Why would you like to reach so many people?

ME: It is a decision that I have taken. I’m not introspective so much, I’m “outrospective”; I’m very social and I want to communicate with people. If I want to reach people on the other side of the globe, I have to find a language that is easily understandable. Do I want to turn to abstract color painting to achieve this? Or do I go deeper into something that is more interesting to me but which is more dangerous, like symbols.

MG: How did you choose your symbols?

ME: If you had a pyramid of the most understandable human symbols – look at advertisement strategies – sex is first. Then symbols that relate to wealth and prestige. A painting of a lake is probably the least attractive.

MG: You recently had an exhibition in India. Does an Indian viewer need to be surprised in the same way when looking at your painting as someone from London?

ME: Yes.

MG: Do you want to give them a sudden moment of estrangement through which they get a flash of awareness that everything is constructed and therefore possible to change?

ME: Yes. Besides, I want to leave a bad taste in the mouth of the viewers. It’s a game. Why should I make art telling people that everything is okay? For this they have the TV, Obama, and other people. I want to leave a message in the painting that is meant for the subconscious without speaking out loud, and this message is not always a good message.

MG: Could you give me an example?

ME: People sometimes come to me and say: “You know, your paintings are sometimes uncanny to me.” So I ask what makes them uncanny. “I can’t read them, I don’t understand what drags me into them, it is like a spiral. I get can’t them out of my mind.” If you make an advertisement that’s exactly what you want. The uncanny feeling that something doesn’t want to leave you, like a melody.

MG: You have said that you don’t provoke too much because then people switch off. If you wanted to provoke, what would you paint?

ME: It is extremely easy to provoke. Theo van Gogh was killed in Holland because he provoked; you had street protests because of the Muhammad cartoons. You take a religious subject and then you have attention. I’m currently working on a new series that depicts women with weapons, like Jeanne d’Arc. Sometimes I think that we never left the Middle Ages. Isn’t it by the way ridiculous that people were protecting their bodies by carrying twenty to twenty-five kilos of metal on them?

MG: I think that we do have a different perspective. In the Middle Ages everything was perceived through the idea of God. Do you think that we have this kind of general idea now? Do you think that there is a concept that consciously or subconsciously arranges our behavior and perception of things?

ME: All the wars that we are now fighting, are besides being effects of economical reasons effects of beliefs.

MG: But you don’t often hear of people who meet a devil while going for a walk, which was not unusual in the Middle Ages.

ME: Maybe these kinds of ideas are still there but not on the surface. There are many people on our planet who live with a totally medieval mindset, being convinced that their belief system is the right one, in the same way as we are convinced that our liberal system is the correct one.

MG: How did you get interested in the Middle Ages?

ME: Our view of history is shaken. History only exists when someone writes it down. Memory doesn’t exist, as it changes every time. The series Game of Thrones, which is a very successful TV series worldwide, is a fantasy world not related to any system, but the young people believe that this was how history really was. History it is always invented by the person who is writing it down, who has the power to change it.

MG: Obviously. By the way, writing objective history was a German invention; it was your Ranke who wanted to describe history as it really happened. Today we realize that there is no such thing as neutral history writing.

ME: I just heard news about Gaza. One station said: “Ten people were killed.” The other station said: “Nine people and a child.” It is totally emotional broadcasting. Just as art is totally emotional.

MG: Is it really? Don’t you think that art has become art in the full meaning of the word because there is an element of control in it and conscious decision: I as the artist make art?

ME: Have you ever been to an art fair? Who makes decisions at art fairs?

MG: The system. Allegedly personal decisions are made through the system, but still we have made the system. If we extend your attitude further, there is nothing conscious in our lives.

ME: Exactly. Nothing is.

MG: Do you think that your paintings are a result of your consciousness of the subconscious?

ME: It is the result of a long thinking process about what I want to express, the content I want to express by reaching as many people as possible at a distance. My dream is that people have to like it. I always have respect for the masses. I believe you can hypnotize people with paintings . . . But it’s a secret – I can’t tell you.

MG: Do you think that there is progress in painting?

ME: Not nowadays; these days painting is dead.

MG: In the 1990s when you studied, painting was declared dead. Didn’t you mind?

ME: No, because painting is the only thing I can do, besides some psycho-tricks. The other serious people in the academy defended painting. I just did it. I smear stones paste, pigments on fabric with animal hair held by a piece of wood, what is that?

MG: There was always a reason for this. There was always an idea: to serve God, to create beauty, to mimic reality, to reflect. What do we have now?

ME: I don’t know. I would need to see all of them to tell. I’m totally outdated. I don’t care, I was never “in” so I cannot be “out.” It’s very hard to be a hotshot.

MG: You were in the Gallery Eigen & Art when the hype of the Neue Leipziger Schule broke out. How did you experience this?

ME: I told my gallerist to keep me out of it. At that point I had been to Leipzig twice in my whole life! I don’t want to be part of a movement that I don’t belong to. People always like to generalize. Now I also work with the gallery Hauser & Wirth, and they have nothing to do with this. Both my galleries do an excellent job by the way.

MG: Still, you became very hip at the time.

ME: No, I will become very hip in twenty years.