Mark Grotjahn

Published: January, 2013, ZOO MAGAZINE #38

The career of LA artist Mark Grotjahn has taken off in spectacular way over the last few years. His exceptional works but also his unconventional behavior keep surprising the art world.

MG: Let’s start from the beginning of your job as an artist: you finished your artistic education at Berkeley then opened a gallery in LA. Why didn’t you concentrate on being an artist only?

MGR: The gallery that we opened was not exactly a commercial space. At that time there were only a few galleries in LA that would give a solo show to a young artist. So, for a young artist, the only possibility would be a big group show. We thought we had a better eye than other galleries and we decided to organize straight up solo shows. We have always thought that we were artists in the first place so we created a beautiful space in which the artists could do the show and the public could see what artists were capable of doing, not just showing one or two small objects.

MG: Why did you want to become an artist at all?

MGR: When I was 15 my art teacher showed me the book Concerning the Spiritual in Art by Kandinsky, in which I found an answer to what I was doing. It opened my eyes to the fact that the designs and drawings I was making could be considered art. In a way, this is the moment when a certain kind of my art education started. So from reading Kandinsky I went to Paul Klee, then to Schnabel and Baselitz.

MG: Always the painters?

MGJ: No, not always the painters. I went to Richard Prince and Mike Kelley as well.

MG: So always a very strong visual appearance.

MGJ: Yes. Although I also really like the dry conceptual works like those from Adrian Piper.

MG: One of your first well-known projects was a conceptual work – the Sign Exchange program that you started at school in Berkeley and in San Francisco and continued while running the gallery.

MGJ: I started it as a reactionary work. When I was in Berkeley, everybody was doing figurative work; barely any of my colleagues knew who Mike Kelley was. I was really bored with the work I was doing so I decided to give up painting the figure and started looking at people using painting and drawing but communicating effectively through these media. This drove me to the Sign Exchange program: people would paint a hotdog for a restaurant sign, or a picture of beer or hamburger because that was what they were selling. So I started to copy this work and tried to exchange my replicas with the “original” works.

MG: What was the reason for this exchange?

MGJ: When I started the project I thought that they were better than mine because they were communicating with their audience. I wanted their audience so I started to trade the signs in order to get their audience.

MG: Didn’t the restaurant owners think you were crazy?

MGR: In 90 percent of the cases when I tried to trade signs I was successful. Some of them thought I was weird, some of them thought I was funny. Sometimes they just wanted to get my sign and get me out of there as quickly as possible. Sometimes the owner would let me go to the back of the store and I would get to see where they kept their guns and money.

MG: Then you brought the ‘real objects’ to the gallery and you showed them as objets trouvé, like your art works.

MGR: I considered them as my art, although they were not found objects but traded objects.

MG: Was it a kind of exploration what makes art art?

MGR: I intellectually believed that art can be whatever you wanted it to be, but only by doing something does the idea become true. It is one thing to say you know something mentally but it is another thing to actually know it, physically. It is one thing to say I believe art can be like this and another thing to do it and know it.

MG: So you did it.

MGR: I did. I moved out here, opened the gallery, worked with different artists and took care of my conceptual needs in terms of working outside of myself, being with other people, like being in a band. Artists love to work and they love to talk about their work. It is great. Those were different kinds of human connections. At a certain moment, I started to look at why I got into art in the first place, why I was interested in art. Then I thought about line and color and then I started to make abstracts.

MG: Did you start to produce different paintings and drawings?

MGR: I was actually looking for one or two motif to exploit. I think because the Sign Exchange was a conceptual work I was always coming up with different ideas. I wanted to pick one idea and stick with it. See what I could do with one motif.

MG: So while doing abstract paintings and drawings you were looking for motifs that you could use as a structure.

MGR: Yes.

MG: This was the second part of the 90s and that means an extremely difficult time for painting; there was a clear anti-painting attitude constructed by many art theoreticians and art historians. Doing painting in the second part of the 90s was not so obvious.

MGR: That is partially true, especially regarding the handmade works where you could see the artist’s hand. At that time, I was also thinking about Gauguin, which was a very romantic notion of the artist. So again, it was a kind of reaction to what was going on in LA at that time.

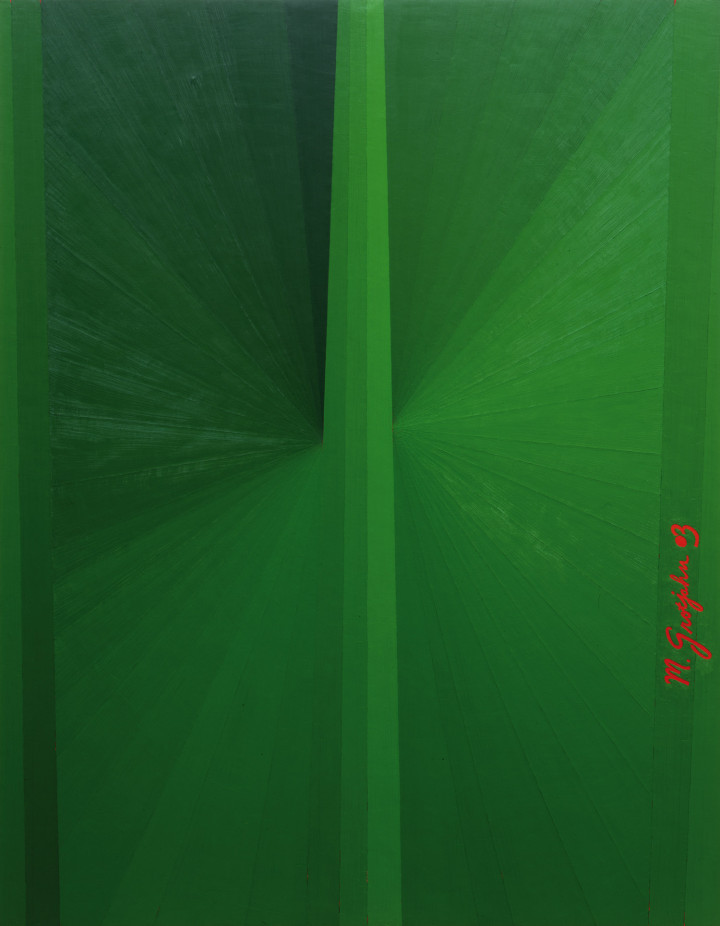

MG: You were playing with the romantic notion of the artist and with the historically-oriented media and then you discovered that the mathematical perspective could be an option for a structure in your work. Did you realize that by doing that, you would immediately connect your works with art history?

MGR: While I was making the three-tier perspectives I was thinking of Kandinsky, Mondrian, etc. I thought I was doing non-objective work. I no longer see it like that in retrospect. I knew that the history of non-representational painting is already more than 100 years old and I knew that I’m part of that language. But it is like playing in a rock n’ roll band and asking: are you aware that you are part of the history of rock n’ roll?

MG: Still, using perspective is perhaps more than that, because the introduction of perspective was an extremely important moment in art history when painting became taken seriously since there were scientific methods applied to it.

MGR: I have never thought about my works in this way. I really like to have my cake and eat it too. Yes, I call them perspectives but I never saw of them as perspectives; I saw them really as non-objective. When I look at them, of course, they do look like roads or landscapes but I never thought of them in these terms when I was doing them. That came from other people and I think it makes sense they saw them in those terms especically considering the fact that I did call them perspectives. It was naïve of me not to have not seen them in their relationship to the scientific, the Renaissance, etc., but I just didn’t.

MG: What about the multiple vanishing points? Was it to experiment with optical effects?

MGR: It was strictly a formal device that I found interesting. That doesn’t mean that I didn’t find it interesting because of my knowledge of art history; I never thought of it specifically as an idea.

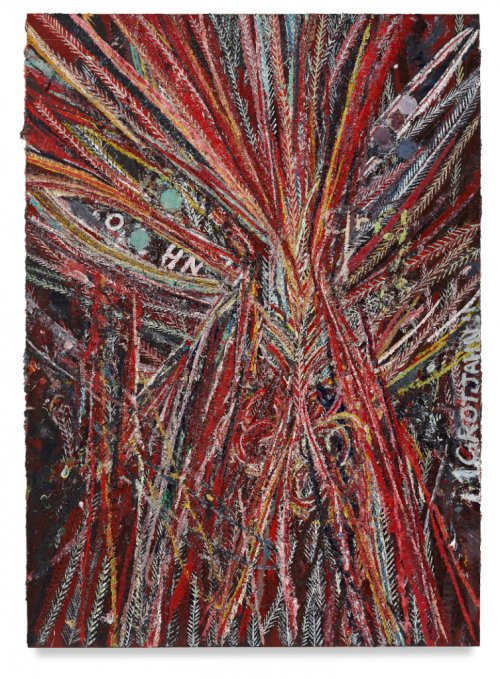

MG: Did you intend to make your works more controlled and less emotional by using these geometrical and mathematical devices?

MGR: Mondrian is geometrical and still highly emotional. When I went onto the ‘Faces’ I used different marks that are, I think, traditionally seen as expressive. The perspectives were very meditative and this is a different kind of emotion. There was a certain kind of peace and a certain kind of beauty that I was going for. I don’t think they are less expressive; it is just that the other ones, the ‘Faces,’ are viewed as more expressive.

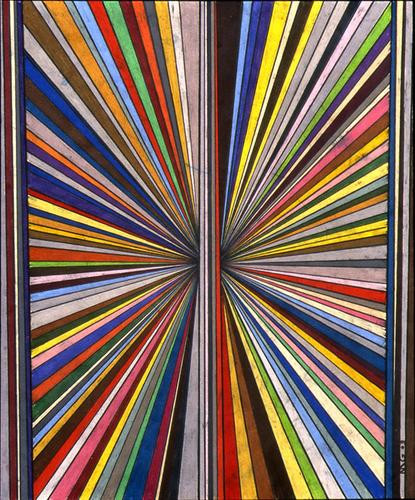

MG: Speaking of contemplative and beauty, let’s go to the motif of the butterfly, which at some point arrived in your work.

MGR: The butterfly came because I tried to make some horizontal three-tier perspectives; the majority of my work is vertically orientated so I tried to work outside of that and make a painting with a horizontal orientation. I made the first two tiers vertical and I pointed the perspectives towards each other. As soon as I did that, and applied the color, it became a non-objective painting again. I got out of landscape. It certainly became more a painting and less a representation.

MG: Did you call it a butterfly yourself?

MGR: I called it a butterfly but it is just a way to categorize it as a group of works.

MG: When you read articles about this category, many art critics connect the butterfly motif with nature. Did you make this connection yourself as well?

MGR: It was not exactly what I was thinking about. I called some paintings perspectives but I’m not interested in perspective; I called some butterflies but I don’t think they are butterflies; I call my sculptures masks but they are not masks.

MG: You play with us.

MGR: I guess I play with words.

MG: There seems to be plenty of opposition in your works. You just mentioned one: contemplative versus expressive. Could we go further to say rational versus emotional, chance versus conscious decision, abstract versus figurative? Do you need them?

MGR: I don’t know whether I need them. Maybe somehow it is important for me to have structures to keep myself interested in making a work.

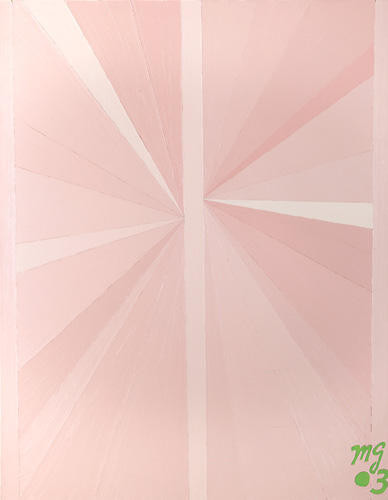

MG: Do you create the tension yourself?

MGR: It happens; I don’t consciously create it. I see it running through the work. It might be that I need the opposition in my work. I just consciously choose to work in different styles. When I moved here, nobody was signing their works because it was the cliché of the artist taking all the credit for the work, putting their ego in front. All of the work that was being shown in the hip and cool galleries in LA was conceptual work and nobody was signing their work. It was another cliché or an unwritten rule that I wanted to challenge.

MG: This is why you enlarged your signature on the canvas.

MGR: Yes, I put it in front and center. I wanted to say: stop thinking that as an artist you don’t have an ego and you don’t have a signature style. I wanted to challenge that: Actually, I am an artist, I have something to say, clearly I have an ego, I have the need to put this work in a gallery, and I want it to be seen. I definitely do.

MG: So you were not extremely popular among the conceptual artists.

MGR: No, I’m still not.

MG: How do you work? How long does it take to finish a painting, for instance a butterfly painting?

MGR: About three weeks, working 17 days straight. I couldn’t stop because otherwise the paint would start to change in consistency. But I haven’t made one since 2008; it’s been a while.

MG: I read that you injured your shoulder a couple of years ago and this is the reason you cannot make them any longer.

MGR: While skiing, I hit some ice and I went down. There was no choice in the matter so I went down. I didn’t see a doctor for two weeks until my wife told me that I should see one. He said that there was something wrong and my arm turned out to be broken. I couldn’t paint two hours straight, let along ten straight. I moved to the ‘Faces.’ This is something I could paint, I could look at, and step back from.

MG: You don’t have any assistants?

MGR: I do have assistants, but my assistants don’t touch my paintings once a painting has started.

MG: Were you sad that you were forced to stop the butterfly paintings?

MGR: I don’t know whether I was sad. I knew that I had to stop for a while and that I might go back to it when my arm recovered. I just never did.

MG: Your recent exhibitions were with bronze sculpture which you called masks – interesting and provoking works. Again there were many comments on the dialogue with early modernism or folk art. You had always made them out of cardboard, so it was a special decision to make them in bronze. I also read that you considered them very personal, not for public consumption. Why did you decide to show them anyway?

MGR: I kept them private for 13, 14 years. I gave them away to friends or occasionally traded one. At a certain moment, I wanted to do a show with them. When you cast them in bronze they become different. In a way, I depersonalized them; they feel less as a diary and are more an armature for a painting.

MG: Let’s now talk a bit about the place you work and live, Los Angeles. Los Angeles is now considered as a very important artistic hub. Is this true for you? Is there a sense of an artistic community?

MGR: There are many galleries and many new spaces that I haven’t had the chance to visit yet.

MG: Are you so extremely busy with your own work that you don’t have time to visit other shows?

MGR: I’ve been into making my own work and not spending a lot of time looking at other galleries. I work five, six, sometimes seven days a week. You can see in the butterfly works that they are very obsessive. I am a compulsive person. When I’m not making my work I feel that I’m wasting my life.

MG: What makes you so popular among collectors nowadays? If you speak with American collectors, many of them admire you.

MGR: It is true. I guess I am popular. There are many peoples who would like to have my work. I don’t know what it is that I’m doing. For a long time I wasn’t like this.

MG: You really don’t know why Mark Grotjahn is considered the artist?

MGR: Am I the artist? I would like to be that, it sounds good to me.

MG: You have been part of the Gagosian gallery since 2007. Were you surprised when they asked you to join?

MGR: No, it was like a two-year process. I had three galleries already – Anton Kern, Blum & Poe and Shane Campbell.

MG: Many artists complain about the pressure of huge production for the market. Once you are with top galleries you are more or less obliged to produce many art works for the market. Do you mind?

MGR: I like to be rich. It is easier to be rich than to be poor. 100 percent. It is easier to have too many people wanting your work than to have nobody wanting your work. It is hard to be an artist no matter what, but it is harder to be a poor artist than to be a rich artist.

MG: But don’t you mind the pressure of delivering all the time works of a very good quality?

MGR: I don’t have to produce a lot. It is up to me. Since all my work is really handmade I don’t really produce that much; I wish I produced more. I wish that I was like Jackson Pollock and I could make a few paintings per day. He was a genius. But unfortunately I’m not that good so it takes me three to four weeks to make a good work.

MG: He had to hurry up, he died very early.

MGR: He died at 44, my age. I would like to produce a lot, but it is not the way I work. I try not to put out paintings that are not good. Here in the studio, sometimes I think they are great but then I try to look at them for at least six months before I release them. I’m pretty good at that.

MG: How interesting. Do you rework them sometimes?

MGR: Sometimes, but I just like to keep them around, at least three or four months to know whether they are good enough. In my mind, they might be good but I’m not always the best judge. If my work goes out and is not good that’s my fault, not the market’s fault.

MG: How many paintings are you producing per year?

MGR: 10 to 15 per year. Van Gogh did 800 the last ten years of his life.

MG: I can imagine that you like the idea that your paintings have become so expensive?

MGR: Yeah… All my high school girlfriends think they shouldn’t have broken up with me.

MG: How did it feel when you recently heard that one of your paintings was sold for $4 million at an auction?

MGR: I watched it live online, and it got me high.

I have personally never sold a work for that much. So this guy made more money on one of my paintings than I have ever made on one of my paintings. .

MG: In the end, this auction was also a kind of advertisement for you. Everybody knows that Mark Grotjahn is now worth $4 million.

MGR: I grew up looking at Picasso books, they seemed like magic to me. I want artists to own buildings; I want them to have financial power.

MG: Of course, there were great artists in history who were rich and very much involved in making money for themselves. What do you think about the role of the collectors nowadays? If I get you right they shouldn’t make more money with your paintings than you.

MGR: It is okay. I guess it is what I signed up for. I’m just sometimes disappointed that someone sells my work and he is one of the collectors who used to put an arm around me and say, ‘I will never sell your work, not even for five million dollars, never.’ And then they don’t want me to come over for Christmas because my painting is no longer on the wall because they sold it without telling me.

MG: Did it happen often to you?

MGR: Yes, it happened enough times to me that it is not shocking any longer.

MG: The idea of money must be comforting when you are making your paintings. When you work, do you sometimes think about the fact that the object you are creating can become so valuable and expensive?

MGR: I don’t let the fact that I sell my paintings get in the way of trying to make the best painting possible. I don’t take phone calls from my dealers when I’m working. I don’t want them to get into my head. So I have ways to protect myself against that and from it coming into my studio. But occasionally, I have to talk with my bookkeeper about the insurance on works.

MG: It must be interesting. But it is not only about being able to work. It’ s also about the very nature of the works. Your paintings are often connected with the idea of transcendence and spirituality; you said yourself that art started for you after reading Kandinsky’s “Spirituality in Art”.

MGR: When I was a teenager I believed that you could connect to this universal language. I don’t believe that any more, I believe that there is a language that you learn and that you can understand. Of course, I would like my paintings to be transformative; I would love my paintings to make someone happy to be alive.

MG: Do you think that your personality – you know what you want, you are provocative, playful, intelligent – is important in positioning your work in the market?

MGR: A few years ago a friend of my overheard my dealers talking to some collectors, they were telling them that I have narcolepsy, that I like to gamble, that I go to strip clubs, and of course they were using that as a marketing tool. Probably still are. The culture of the artist is extremely interesting. I love biographies of artists.

MG: From what you said about being an artist, I think that you like to cultivate the romantic idea of the artist, to break the rules, to be an outsider, to provoke and challenge assumptions.

MGR: At the same time, to be very traditional. I have two beautiful girls, I have a wife, a house. But I am an artist. It is a weird thing to be one. You come to work and you do this. This is a choice but it is a strange life.

MG: You chose to be involved in a court case against one of your collectors. Did you enjoy it?

MGR: Enjoy it! I hated it, it was terrible.

MG: It was unprecedented, what you did as an artist.

MGR: I’m in a position that I can afford to hire a lawyer to fight someone who doesn’t want to pay royalties. I didn’t enjoy doing it, but I felt like I didn’t have a choice.

MG: Did you want to set an example on behalf of other artists as well?

MGR: I did it for myself but I think it was important to do it.

MG: Are you part of the private life of many collectors?

MGR: I try not to be anymore. Because once you go skiing with them, all of a sudden they expect a painting from you for the price of a lift ticket.

MG: Do you consider yourself as an American artist?

MGR: I’m American although my father was born in Germany; I’m a first-generation American.

MG: Now I understand your name! I thought it was more Dutch.

MGR: All Germans are saying it is Dutch but it is German; it definitely traces back to Prussian roots. But I have never met any German who would give me the credit of having a German name. The maiden name of my grandmother was Gross, which is definitely German.

MG: It must be amazing what has happened to you the last 10 years.

MGR: Yes.