Kour Pour

Published: January, 2015, Die Welt am Sonntag

The 27 year-old artist Kour Pour has became known for his elaborated carpet paintings that play with familiar symbols of different cultures and universal concepts of beauty. In his studio in Los Angeles Pour talks about his art, the cultural context of his works but also about his attitude towards the art market, which has become an indivisible part of artistic practice of many artists of his generation.

MG: We are now in your studio in Los Angeles where we are talking about your upcoming exhibition at Depart Foundation in Los Angeles, your past exhibition in New York and the current exhibition in Dublin. When did it all start?

KP: I knew as a child that I wanted to do something creative. As a teenager I really loved hip-hop music, which I discovered in LA while visiting my relatives.

MG: You were born in England.

KP: Yes, but my father has family here so we would visit them as often as possible. My first memory of LA was hearing hip-hop music on the radio. I became fascinated by the sounds that were used in the songs and even had the idea of becoming a music producer. When I finally moved here I went to community college while waiting for recording school to start and took some art classes. Then it just happened to me, I fell into art.

MG: Do you still dream of recording music?

KP: Maybe one day but there is so much that I want to do in my practice, so I have to be focused. Even though when I’m making a painting with different imagery and layers, it is almost the same as making music. Especially with hip-hop where there is a lot of sampling from different sources that come together to create something new.

MG: Your paintings function as visual hip-hop.

KP: I didn’t think about it until recently when I started to compose the designs on the computer. There are several different layers in my paintings and somehow they need to harmonize with one another and for this you use different effects and techniques, as with music. There are parallels.

MG: You wanted to be an artist; did you also have an idea about what direction it would take?

KP: Partially, the exciting thing about starting a body of work is that you don’t necessarily know where it will lead you. You are always learning and progressing and you let the work take you to places without a map or a plan. When I started the carpet paintings I directly appropriated the images of rugs from catalogues. I didn’t know that it would lead me to designing my own paintings.

MG: Why were you so fascinated by carpets?

KP: At the beginning I was very much interested in the public life and proliferation of meanings that images could hold. The design of a carpet starts off on crate paper – now they probably use the computer – the colors are distributed in squares, each square represents a knot or pixel so the weaver can use this image as a reference. Then a carpet is made and photographed. I would find the photograph and turn it into a painting, which is also photographed and displayed on my website. I was really interested in how these circles transform objects in different ways.

MG: Were the carpet paintings your first serious paintings?

KP: Yes. I made the first one in my last year of school. I tried a lot of different things at school before getting to that point.

MG: Do you intend to continue them as an ongoing series?

KP: Yes, especially now that I’m also designing them myself, it is so endless. For me there is a personal history with the carpets, the object is full of cultural references and I’m also interested in how it functions in the market place, as a produced object.

MG: Let’s analyze the three aspects that you just mentioned: the personal, the cultural and the economical. Why do the carpet paintings have personal meaning to you?

KP: My father had a small carpet shop in England and I remember being in the shop when I was very young. My father moved to the UK from Iran when he was only 14 years old. He and my uncle were on their own in England, they didn’t know English at the time and because of what was happening in Iran they never went back. Later on my father met my mother, who was British. I think they were only 19 when they married, and they were fighting to support themselves. My dad worked a lot of different jobs but the carpet shop was always memorable to me.

MG: Do you identify yourself somehow with Iran or the Persian cultural tradition?

KP: It is weird. My father speaks Farsi but as he was working all day long I never learned from him. Besides, when you leave your country so young as he did, it is easy to become distanced from your culture. I can see it with my younger brother, he left England when he was 8 and grew up in American culture.

MG: You inherited a very exotic name, while you are a western American – English person. I could imagine that because of your name people associate you with something completely different than what you are.

KP: I’m not exactly sure what I am, but that makes sense. I know Iranian food and the culture but I don’t speak any Farsi. On the other hand, I grew up in the South-West of England in a small city and never felt or looked very British. Now I live in Los Angeles and all of a sudden I’m British because of the accent. I remember going to Heathrow airport for the first time and feeling very much at home amongst the different cultures and people.

MG: How do you choose signs and symbols for your paintings?

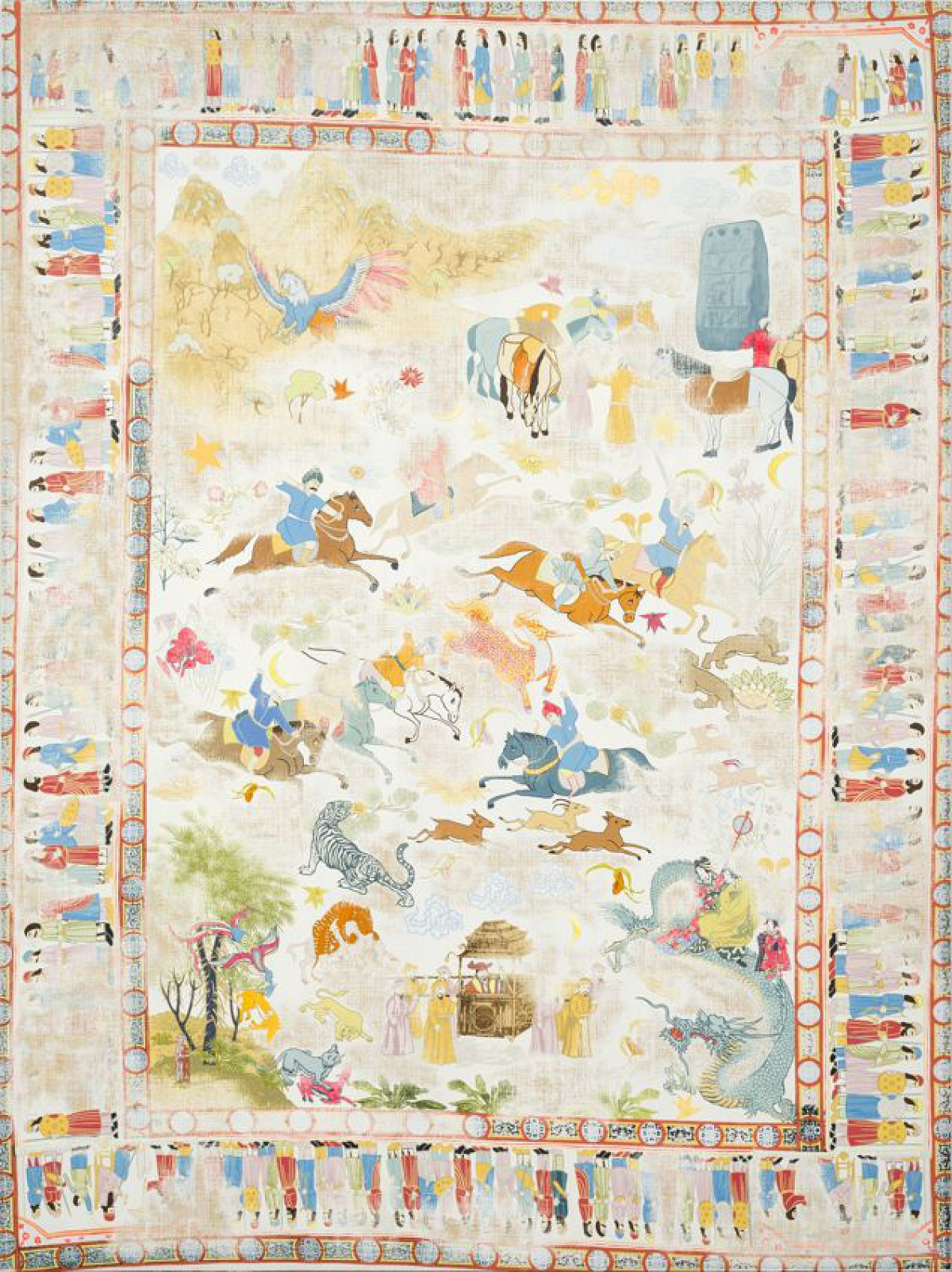

KP: The early ones were based on the patterns that I grew up with; the later ones that I showed at Untitled in New York were more specific because I chose carpets mostly from the 16th century. You can see images of dragons, monks and Portuguese sailors. These carpet designs were influenced by the experiences of trade and exchange with the Europeans, Indians and Chinese. Partly because these carpets are very rare to find and I had exhausted my material, and also because I was interested in the carpet format as a kind of historical record, I started designing my own compositions on Photoshop using imagery that I could find on the Internet. I see my own designs as records of the way we collect and exchange information today.

MG: Do you have special rules on how to structure an image? For example here we see a few ancient Egyptian gods, Roman buildings and horses from Persian miniatures. Do you intend to speak a global language of images?

KP: Before I started these works I thought that I could do them in one of two ways: one would be to tell a specific story and place certain images next to one another to recount historical moments, myths and stories. I’m not necessarily trying to tell a particular narrative, so I decided for the second option, to use these signs and images as formal elements, freely placing one thing next to another on the same plane.

MG: Is a formal harmony very important to you?

KP: I want to make a strong and beautiful painting but what is also interesting for me is the way that I’m finding the imagery by clicking from one link to the other; I feel as if I’m travelling through time to different locations. I’m drawing from a lot of universal and iconic images that are sometimes related, or have nothing to do with one another and making compositions that flatten time and space.

MG: Is this lack of specificity a reason why your work is so appealing?

KP: With the new work I think that people can relate to all the different images, in that sense perhaps they are more universal and represent a global audience. During my show in NY I noticed that people responded to the formal and decorative aspects of the paintings. Many people react emotionally to the carpets because they are nostalgic objects from their childhoods and family. The carpet is also an iconic image in itself.

MG: You want your paintings to be beautiful. Don’t you mind that the idea of beauty has long been abandoned as a concept that is relevant for modern and post-modern art?

KP: Appearance in my practice is important as I enjoy visual pleasure and stimulation, but it is only one element of the work. When people come to visit me at the studio they realize that there is a conceptual side to my practice, which is growing and changing in different ways. Art can be beautiful, smart and interesting all at the same time.

MG: Do you think that the idea of beauty has entered the art field again?

KP: There are fashions and trends in art like anything else, but at this point I think that art can be open to anything. I don’t know if there are any real movements or specific ideas to react against in the same way that artists did in the past. In this sense I think that it is unnecessary to limit yourself to one way of making and thinking.

MG: What are you looking for?

KP: What is interesting to me are the images and objects that I am referencing in my work. Some are thousands of years old and the people who created them, often with their own hands, believed that they had real meaning or some sort of spiritual or magical power. I really love that.

MG: Would you like the viewer to stand in front of your painting and cry as Rothko did?

KP: I don’t want them to cry necessarily. I do want them to feel an atmosphere, or an aura as Walter Benjamin put it.

MG: You are using reproductions to create an aura. You would confuse Benjamin…

KP: I like that! I think it goes back to the cycle of images again. The reproductions that I’m using used to hold power and meaning, and when I find them in clip art catalogues that are used for graphic design, they definitely don’t feel special. I guess that in some way I want to recharge them and bring them back to life.

MG: Does the atmosphere of LA stimulate your work?

KP: My studio is in Inglewood, very close to LAX airport so I see the planes fly by every couple of minutes. I like thinking about all the different people flying in and out of the city, so maybe that is influencing me in some way.

MG: What does the LA scene mean to you?

KP: There is a history to it with all the schools here such as Cal Arts and UCLA. A lot of important artists live and work here also. I think it can be quite insular at times, which is funny because LA is such an international city. I think that it is slowly starting to change though with all the artists and galleries moving in from other places.

MG: What about your position in the market? You are very young but your works were already auctioned. I know that you are pragmatic about your early appearance in the art market but not many artists had their works auctioned at the age of 27.

KP: Age doesn’t say a lot about a person. I think that I’ve had a few life experiences that made me grow up very quickly. My mother passed away when I was sixteen. She was very young herself, only 40 years old. Through this experience I learned that life moves very fast and that you should spend your time by doing what you want and love. Maybe this is why I’m so focused.

MG: Don’t you think that art needs time to become mature?

KP: I just had my first show this year but I started studying art in 2006. From 2007 till 2010 I was in art school and had a very good peer group. From 2010 to 2014, apart from having a full time job for the first couple of years, I was here in the studio every day. That’s a lot of hours that I’ve spent developing. It’s the 10,000 hours rule that Malcolm Gladwell talks about in his book Outliers.

MG: It seems that you were even playing with the market in your works.

KP: Some of my earlier paintings are based on photographs of carpets from Sotheby’s and Christie’s Oriental rug sale auction catalogues. Now I see my paintings in the contemporary sale catalogues, which is a very surreal thing. It’s pretty funny really, and goes back to my interest in the cycles of images.

MG: What about your audience? Are you aware of them?

KP: There are so many audiences really. I’m getting emails from people in Europe, Japan, Middle East. There are so many eyes because of the Internet. It changes the meaning of work as well because it doesn’t pursuit one central artistic canon. I’m now reading a book about Chinese landscape painting, and they have different ways of creating and experiencing an image than we do here in the West.

MG: I’m reading now the biography of Willem de Kooning. In the 40s and 50s he and some other artists formed a group in New York, who met several times per week to fight and discuss art and who had a sense of a small community and a exclusiveness of their artistic ideas. Does it differ a lot to the current practice?

KP: I also have artist friends who live down the street whom I see every day. The idea of a community is still there. We discuss art together but at the same time I can also have discussions with people that I’ve never even met through email and Skype, so the idea of community is a lot wider than before. Abstract Expressionism was very specific and reacted to something very specific. What I make is very different to what my peers make, it’s a diverse group of people with diverse ideas about art. I think that what’s interesting are the in-between or liminal spaces of polar ideas.

MG: What is your next project?

KP: Well, I just had my show in Dublin last month for which I made a body of works based on woodblock printing. I made paintings, clay sculptures and aluminum reliefs using the lost wax process.

MG: Why is it so appealing to you?

KP: I wanted to address the ideas of recording, sharing and distribution in a more direct way. I like the history of woodblock printing because it was the earliest form of reproduction. It was used to print patterns onto fabric, and texts that were responsible for spreading ideas about religion and philosophy, such as Buddhism. Both clay and wax were also very early materials used to record information such as trade transactions or governing rules of civilizations. I also enjoy that with woodblock printing you see the negative space of the image, the part that has been carved away becomes present. I’m open to using different processes and materials that take the practice to new places. In my next show I’m going to introduce incense powder.