Joan Semmel

Published: December, 2022, Interview for the book "New Waves. Contemporary Art and The Issues Shaping Its Tomorrow"

April, 2020

Marta Gnyp: How are you doing in the corona time? Has the quarantine changed your normal way of working?

Joan Semmel: It’s a very difficult time. Emotionally it’s surreal. Everything is so strange because the streets are empty and it’s a kind of suspended time and space; a lot of the stores have boarded up. When I go down to get some air, it feels like you’re walking through a de Chirico painting. The building is sort of caving in on you; the lights and everything is totally surreal.

MG: Especially in New York that has been hit very severely.

JS: It’s the worst here, I think. How are things where you are?

MG: Berlin is probably the best place to live in at this moment. The lockdown was moderate, we were asked to stay at home, but we were allowed to walk on the street by two; I could jog in the park, I could walk everywhere and work alone in my office. The numbers have been good in Germany. People have been disciplined and it’s getting better. The shops and galleries could reopen last week. There’s hope that there will be no second wave, but nobody knows really.

JS: It seems like there will be a second wave, and people are getting very restless. New York is a big city. It’s crowded. There are people now at the park where they shouldn’t be. Everybody’s worried about the economy. People have lost jobs. It’s just really kind of apocalyptic time.

MG: What about your work? As a painter you are probably used to work in isolation and in solitude.

JS: I’ve always liked that isolation. I like being in the studio alone, putting on my music and tuning out the rest of the world, so it hasn’t affected me emotionally as much as it bothers some people. It’s just the monotony of it: that every day is like the next, nothing changes. You’re in this space without any connections. There’s nothing good to look forward to. You feel like this is an endless kind of cycle of having to pull the work out of your head. There’s no outside stimulation. Going on the net and the television and all that, I find it turns me on; the news is very upsetting. But I’m working – not as much as I usually do because it’s hard to get motivated in this kind of an environment – but we don’t have choices.

MG: Art is being offered massively online now and this is also very surreal because you need to experience art in flesh, at least I can say that’s how it works for me. Of course, we have to work online because there aren’t many other options left now, but artworks start to look exchangeable.

JS: It’s really not the same thing. It’s a very different kind of experience in every way; the scale, the change of scale and the surface, just the glaring lights of the screen. There’s no relationship with the object that you’re seeing; you can’t get into the contemplation of space that you need to see a work of art. The only good thing about it is that it has probably killed the whole idea of the art fair permanently, because people can’t go to that kind of a crowded space. From my point of view as an artist, that’s a great relief. Maybe now we’ll be able to just take a walk in the street and go from gallery to gallery experiencing art in a different setting.

MG: I wonder how this will work out. This year is lost to art fairs, but suppose we will have a vaccine anytime soon, I think everything would go back to previous art market situation. But, let us start talking about your fantastic life as an artist and let’s start from the very beginning. You were born in a Jewish immigrant family, a third or second generation?

JS: Second generation. My mother actually came to the country as a child, but they were part of the whole Eastern-European immigration in the early 20th century.

MG: From which country did your mother come?

JS: I guess it would be Poland at this time. At the time it was still Austria-Hungary.

MG: Did you speak English at home?

JS: Yes, we all spoke only English. The only time my parents spoke another language was when they didn’t want the children to understand it, but otherwise it was always English. It was not a two-language home.

MG: The immigration and Jewishness was never a subject that played a role of importance in your art.

JS: No, it never was. I was educated as an American and my parents were totally Americanized. They spoke the language perfectly, and they were not religious, so never dominated my life in any way.

MG: I read that you were talented in a junior school then you went to the Cooper Union.

JS: At the High School of Music and Art, which was the lower grade, I guess comparable to your secondary school, and then Cooper Union. They were both free schools and they were art schools.

MG: Which means that, from the very beginning, you were interested in art.

JS: Yeah, I was. I was directed at a relatively young age into art because I was considered talented.

MG: Then you did what young women at that time did: you married someone, and you got a child.

JS: Yes. I married at nineteen and my daughter was born when I was twenty-three. At that time, I had not painted for a couple of years. I also had an illness; I was hospitalized with the tuberculosis and spent six months in a hospital. I had a major surgery.

MG: Did this illness change the course of your life?

JS: Yes. That was a very important experience, which supposedly was a tragedy, but in a way, it gave me a point in life to think of what I wanted to do with my life rather than just going along. After that, I went back to painting, and started to become an artist.

MG: Interesting. So, one of the conclusions of what you wanted to do in your life was that you really wanted to be an artist?

JS: To be an artist, yes. I don’t think I would have verbalized it that way, but I knew I needed to do something that was for myself, to follow my own needs, and not only be at the service of the family.

MG: How did you start this transformation?

JS: I went to Pratt Institute. In New York at that time, the Cooper Union, which was a three-year program, didn’t offer what is a degree at that point; they just gave a certificate. I wanted to get the degree so that I could possibly teach. I had gone a year and a half to Pratt, got the first degree and after that, I went to Spain with my then-husband where I stayed for seven and a half years.

MG: When you were in New York I understood that you were painting abstraction. Did you have any connection to the abstract New York School group?

JS: I did not because I was just a little bit late in terms of the age to be part of that group. When I went to school, I didn’t know anybody in the art world. It was very provincial, I lived in the Bronx and I had no contact with the people in Manhattan. Then when I came back from Spain, I actually started connecting with the whole art world kind of environment.

MG: How did you come to abstraction?

JS: At Cooper Union. Some of the instructors where deeply involved in the AbEx experiment at that point. My whole education at Cooper Union was very much involved in the whole philosophy of Abstract Expressionism, of the gestural art, the expressivity of it and so on.

MG: With the AbEx American specialization you became successful in Spain.

JS: True. I showed at the best gallery there in Madrid. I have traveled to South America with a big show of thirty-five paintings to the Museum of Plastic Arts in Montevideo in Uruguay, from there it went to the Bonino gallery in Buenos Aires, and I was also scheduled to do something in Brazil, but I opted out of that because I was advised that it would be difficult to get my work back out.

MG: You had a career as a woman artist.

JS: Yes, I was a novelty. Being an American woman making art was a sheer novelty. It gave me an identity immediately. I didn’t get lost in the crowd, so to speak. It meant that I had visibility and respect, but I wasn’t part of their network system. I was friends with Spanish artists. A lot of them came by when I was leaving to give me a party, so it was a good experience all around for me, but I was always an outsider.

MG: Did you like to paint abstract?

JS: Oh yeah, I loved to. I think that’s who I was. Abstraction was where I placed myself and that was the way I worked. I didn’t think that I could do anything else, or that I should do anything else. When I came back to New York, I had a real problem of relating to the kind of work that was being done here at that time. It was no longer Abstract Expressionism, but what they called Color Field painting. I really couldn’t relate to that at all. I also became very passionately involved in the political situation of women in the art world and in the world in general.

MG: One more question about abstraction: have you ever considered to go back to abstraction?

JS: I play with it. I utilize it in my work, I think abstractly and conceptualize a painting in the way I’d put a mark down. All of those things come to me instinctively through the way I always worked as an abstract artist. I don’t separate the two things in my mind. I never felt myself a figurative artist or a realist artist, the two classifications where I could fit. I never experienced my work as figurative; I never thought about being representational as being important, but I thought about the figure as an object – as an icon rather than as representation of any reality.

MG: Perhaps this is why your paintings are so powerful, because it’s really about the color, about the form and about the image as such.

JS: That’s how I thought about it. The reason that I came to work that way, was because I wanted the work to relate to what my passion was at that time, which was to change the way things were for women like me.

MG: Now we come to the limits of abstraction that actually can never really carry a message.

JS: They couldn’t carry any messages at all, but I never wanted the work to be pedantic or propagandistic. I never wanted to be telling you what you have to do. Who knows? It wasn’t even a narrative. It carried a message, but not in that traditional way.

MG: I understand. What had changed you? You were a successful abstract painter, then you went back to New York and became determined to fight for the women’s case and connected with feminist groups.

JS: Well, first with the political groups in general; there was a whole group called the Art Workers’ Coalition in New York. I met a lot of the artists there, many of whom I had not known before. There were all kinds of discussions and panels and talks about all kinds of things very deeply connected to the political movements of the time. The reasons for the connection to the women’s movement were much more personal. That had to do with my own struggles as a woman, freeing myself from the necessities conforming to the woman’s role socially. At that time – don’t forget this was 1970s – things were still difficult for women. You can’t imagine the difference between how it was then and how it is now.

MG: I cannot.

JS: It was different in every way: professionally and personally, in family, in work relationships and political relationships. I had to rethink my relationship to myself and to the world in order to become an artist in that environment because it was so constrictive for women.

MG: New York is known today as a very liberal city and so it’s really difficult to imagine that it was so oppressive to women.

JS: Well, I think it was oppressive. First of all, from your background in terms of what the expectations of your family were and how you internalized that. Then, it was restrictive in the art world in terms of what a woman artist was expected, or I should say, was not expected to be. You were not expected to be certain things. You were not expected to be ambitious. You were not expected to be called a genius. You were not expected to even be confident. You were expected to be a sort of camp follower and serve the man and the art world in various ways, both sexually and physically. There were very few women who were able to break through that.

MG: If we speak about 1970s and we take a woman artist like Lee Krasner, was she an interesting role model?

JS: She was, and she wasn’t, because Lee was a very unhappy woman in many ways, and had served her husband [Jackson Pollock] for how long? She developed his career for him. Even after he died, she devoted her life in so many ways to him. At her own expense, so that I wouldn’t take her as a role model.

MG: You are right. She actually belongs to the tradition of women serving the men first at the expense of their own careers.

JS: That’s exactly what I meant. Elaine de Kooning the same way. They were the role models we had. They worked very hard to get to where they were, where they were at least in a position to be seen as an artist. The women were never seen as being artists who broke any rules or who are leaders in any group.

MG: How did feminist circles work? You met each other, you spoke with each other, you shared certain ideologies – such movements can be also suffocating at a certain moment.

JS: No, it was not suffocating. It was quite the reverse, because there were so many different groups and a lot of explosive, very strong personalities. Women who became professional artists at that time were really courageous; you had to be very strong and very willing to put yourself out there and take risks. We firstly got to know each other in these big political meetings that included men. Then the women broke off because they would never have been taken seriously and formed their own groups; that’s how it began. We used to go around and meet in different studios, each time in somebody else’s studio. We got to see work that was never exhibited, we got to see all kind of wonderful work that none of us could get out, that they couldn’t get exhibited.

MG: Did you discuss each other’s works?

JS: Of course. It was never repressive. It was just the reverse. It became more repressive when the theorists became more active. Back then, we didn’t have words like the male gaze or the woman’s gaze, and that’s how I was working, but I never heard those words, so I never thought of it that way. I thought of my own point of view. It was just a formative time.

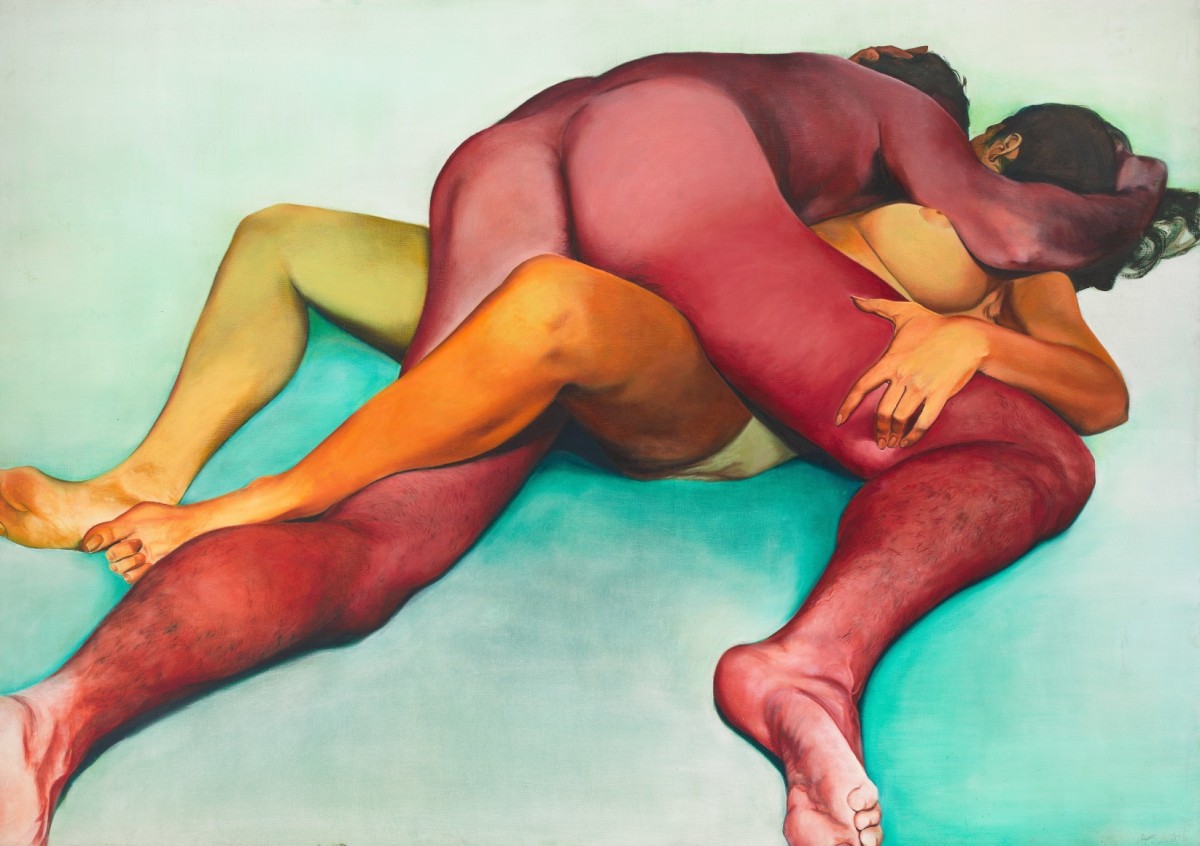

MG: How did you end up making sexual paintings?

JS: People who had similar ideas grouped together a lot. Some of the artists were into painting and decoration, what they called the decorative movement. People like me, we were more involved in the sexual work. We got to know each other, formed different groups to help each other to move the work, to show the work together, to make it into a movement so that we could get visibility.

MG: Sexual paintings became your territory.

JS: That’s right. You got to know other people working in that area, because it gave you a sense of relativity so that you didn’t go crazy. That was important for that kind of thing. We all did very different things; there were people from performance, like Carolee Schneemann to Hannah Wilke, there were just so many of us. There was no formal group, there was no manifesto, but we had certain areas of the work that could be discussed in similar terms so that we could get visibility that way.

MG: It sounds like a group of fantastic characters.

JS: Those were just the ones that came to my mind because I was particularly friendly with them, but there were many more.

MG: What about painting? Painting at that time was considered a more traditional medium.

JS: Well, mine were paintings. Hannah was the sculptural side and photographs; Carolee was performance, so they were all of those kinds of different approaches. I was involved at the time also in writing and curating.

MG: What did you curate?

JS: A museum show called Consciousness and Content at Brooklyn Museum (1977). It was a show of women artists. There were two shows that I curated back then. Don’t forget, back then, women didn’t want to show in all-women’s shows. They felt like it was a negative thing to do. I had to convince people that that’s what we had to do to show the strengths of women rather than to try to fight the kind of constant denigration of our work.

MG: Was there a lot of interest from institutions for your work?

JS: We got a fair amount of attention from the press, but we were never supported by the institutions. There were several people, who were supportive as individuals, but the movement itself was not supported. During the middle of the 1980s there started to be political underground, so to speak, in the feminist movement such as Guerrilla Girls.

MG: Who questioned the role of institutions in discriminating women.

JS: They attacked the institutions; they made it clear that we were being institutionally discriminated against by both the galleries and the museums, and that was why the work could not get any support.

MG: What about galleries? Did you have a representation? Were you selling your paintings?

JS: I never sold much. I sold some. I had a gallery at the time, Lerner Heller Gallery. The self-images sold, the sexual images I wasn’t able to even exhibit at that time.

MG: You were lucky to keep them for now.

JS: Well, I couldn’t get the galleries to show them. Before I had gotten a gallery, I rented a space down on Prince Street in Soho and did a big show of the sexual pieces. It got reviewed very well and it sort of introduced me to the art world in a funny way because it was considered very shocking at that time. That was the first show I did in New York.

MG: How did you make them? If I understood correctly you firstly made the sexual paintings followed by the erotic paintings.

JS: Well, the sexual element was just a title. I needed to name them, so we know what we’re talking about. But they were all what I call the sexual painting, really. The first group came right after when I first left abstraction, so they were more abstract with unrealistic colors and gestural kind of marking. Then, I went to using the photographs and made the more representational realistic paintings. So, I had two groups of sexual paintings, one that came directly from abstraction, and the second where I first started using photographs and started working more realistically. After those paintings, I went to the self-image.

MG: The self-image paintings are extremely exciting. Were you taking photos of yourself and of your partner?

JS: Yes. I took the photos of myself; the pictures with the partner, one or two of them were done by collaging two figures together. I took two separate photographs and then called it Intimacy-Autonomy for instance, where I had two separate photographs that each have their own disappearing point and put it together. I called it Intimacy-Autonomy because that’s what I was looking for in the painting. The others I took with the camera myself, holding it sort of next to my eyes to try to get my point of view. It was a very literal interpretation of how I could show a woman artist from her own point of view.

MG: What was your aim in these works?

JS: I was interested in showing and creating an image that women could respond to as an erotic image without raising issues of shame and dismay like pornography does or did. Nowadays it’s different, because now it’s just another entertainment form. But at the time, for women to express their own sexuality was something unheard of. For women to be able to have desire was still not okay. Women were supposed to not care about sex. They only wanted quote “love,” they wanted romance; they never had a sense of physical desire, this was a different world. I was trying to break down some of that for women to be able to admit their own needs for sex, for women to respond to something that was sexual. To create something visually that would be sexual, but desirous for women, not just projected to the male desire.

MG: Were you analyzing your own thoughts and desires for that?

JS: It was conceptual. I was always looking for, well, how is it different for women? What would make it interesting for women, and not necessarily just for men? When I was making these paintings, it wasn’t about representing my sexuality; I was looking for the triggers that would work for women in general. Obviously, the thought that all women would think the same way is absurd. Different women have different needs, different desires, different points of view, but as a young person at that time, I was going to change the world.

MG: Rightly so. As you said, family was also part of the oppression system unwillingly. How did you get rid of shame that could be imposed on a young woman when showing sexual works?

JS: I don’t know how I got rid of it, but I think that my own experience of first being hospitalized and alone and being in a situation that was that extreme forced me to think about certain things. Then leaving home and going to a foreign country, I was separated from all of those familial kinds of inhibitions, as there was nobody there to tell me how I was supposed to feel. My mother wasn’t on top of me and my father wasn’t telling me what to do, so I was suddenly free, and there was that. So, there were all of those elements in my own personal life that made it possible for me to become myself. The whole idea that the personal is political was a revelation for me.

MG: How did you formulate this concept in order to make it work in your paintings?

JS: This sexual disinterestedness that was put on us, made it impossible for us to be able to really express ourselves in any way. So that we had to begin there to free ourselves to be able to make the kind of cultural contributions that we would like to make.

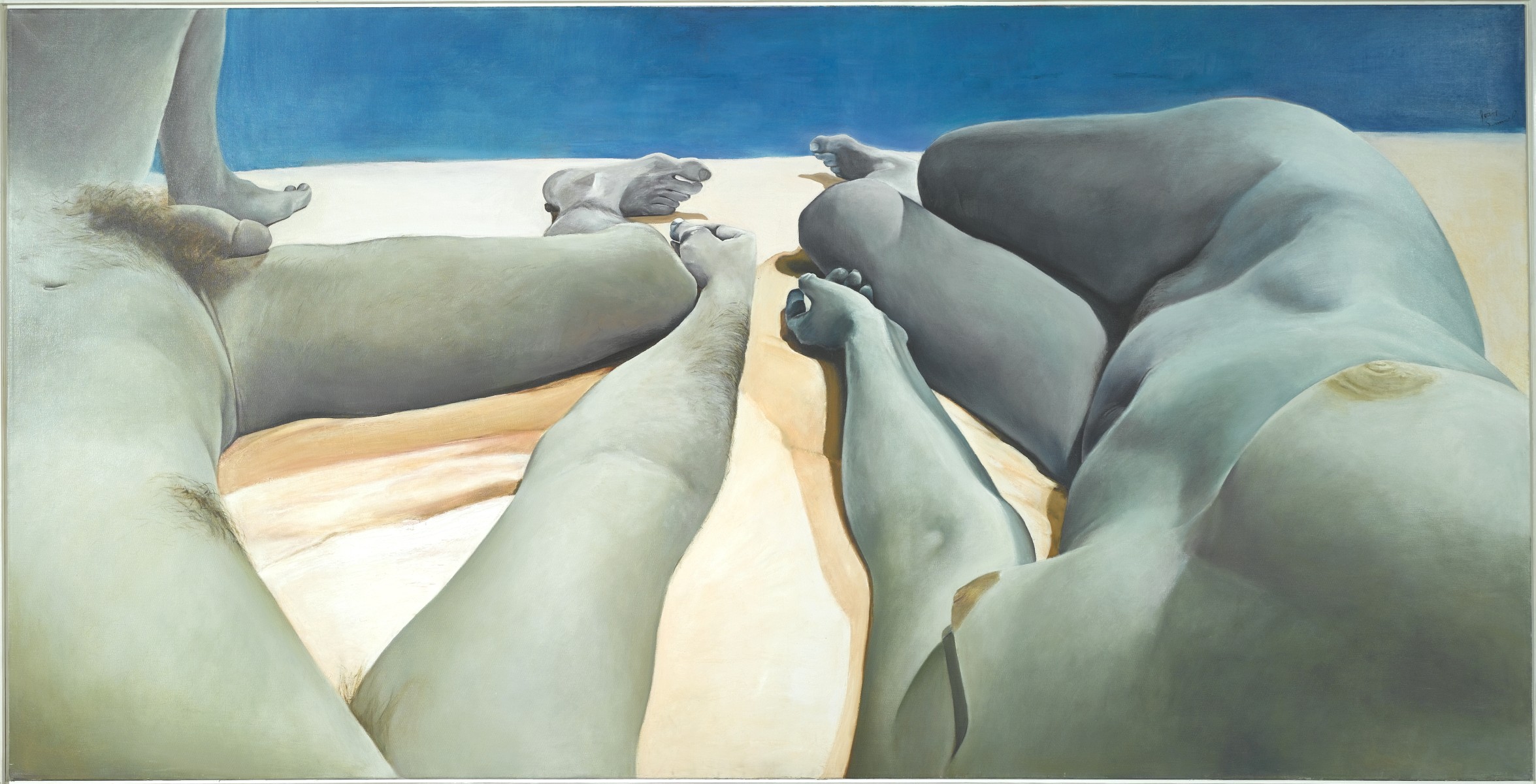

MG: You started the self-image series before 1974, which means that you started to photograph your body at the age around thirty+ and at that time you were a very beautiful young woman. Did you think at that time already that you were going to photograph yourself through your whole life?

JS: No, and I never thought of myself as a beautiful woman displaying her beauty. I never conceived of it that way. The reason I used myself in this was that I wanted to make images of women that were not fetishized. All I saw on the newsstands were images of pin-up kind of women. I felt that it was a false image; it was a commercialized image of selling women’s bodies. I wanted women to be seen in a way that they really were, and with all the imperfections that were there. I wanted to show that the kind of advertising and movies and everything that gave women images of themselves were false and made them always feel inferior and not good enough.

MG: Don’t you think that some women also enjoyed being fetishized?

JS: There wasn’t a woman that didn’t look in the mirror and say, oh, I’m too big here, or too small. They wouldn’t say that if they were the Barbie doll image that was given to us. When I took pictures of myself, it wasn’t that I felt that I was a beautiful woman that wanted to have my beauty displayed as a seductive image; just the reverse. I wanted a real person to be seen, a body that was imperfect, a body that was still sensual, even though it was imperfect; it was not a fetishized object that men made of a woman’s body but rather a human person that they could love. They only saw it as that other kind of thing, which I found offensive and also demoralizing to women. The reason that I used my own body was because I did not want to objectify another woman, especially since I was going to be doing women with all their imperfections. And that it would be unfair to somebody else without their permission. Also, I couldn’t afford models at the time, so I was always available.

MG: I wasn’t suggesting that you wanted to display your beauty, but was curious whether you had taken a principal decision already then to photograph yourself through the process of aging. You’ve been making this painting of yourself for forty years. You have to be extremely courageous to continue because I think that, in our Western societies, we are absolutely not used to see a naked older body.

JS: Well, that came about just naturally in the work. Obviously, I was using my own body and I was getting older. I saw that and I also had to deal with that personally. We all have to deal with that, right? It doesn’t feel great.

MG: No.

JS: When you live in a culture that worships youth, as you get older it makes you feel like you disappear. Those were the things that came up in the work just naturally. I didn’t start out saying I was going to deal with age, but because of what I was doing and in my own body it showed, I understood that this was really also about aging. I started thinking about the aging earlier. I did portraits of my father. I did pictures in the locker room where women of all ages and sizes and shapes were naked, so it wasn’t just that I used my own body. I came back to my body because I felt that in the end that one icon of the body expressed it better than all these kinds of group pictures of women in locker room and in gymnasium kind of setting.

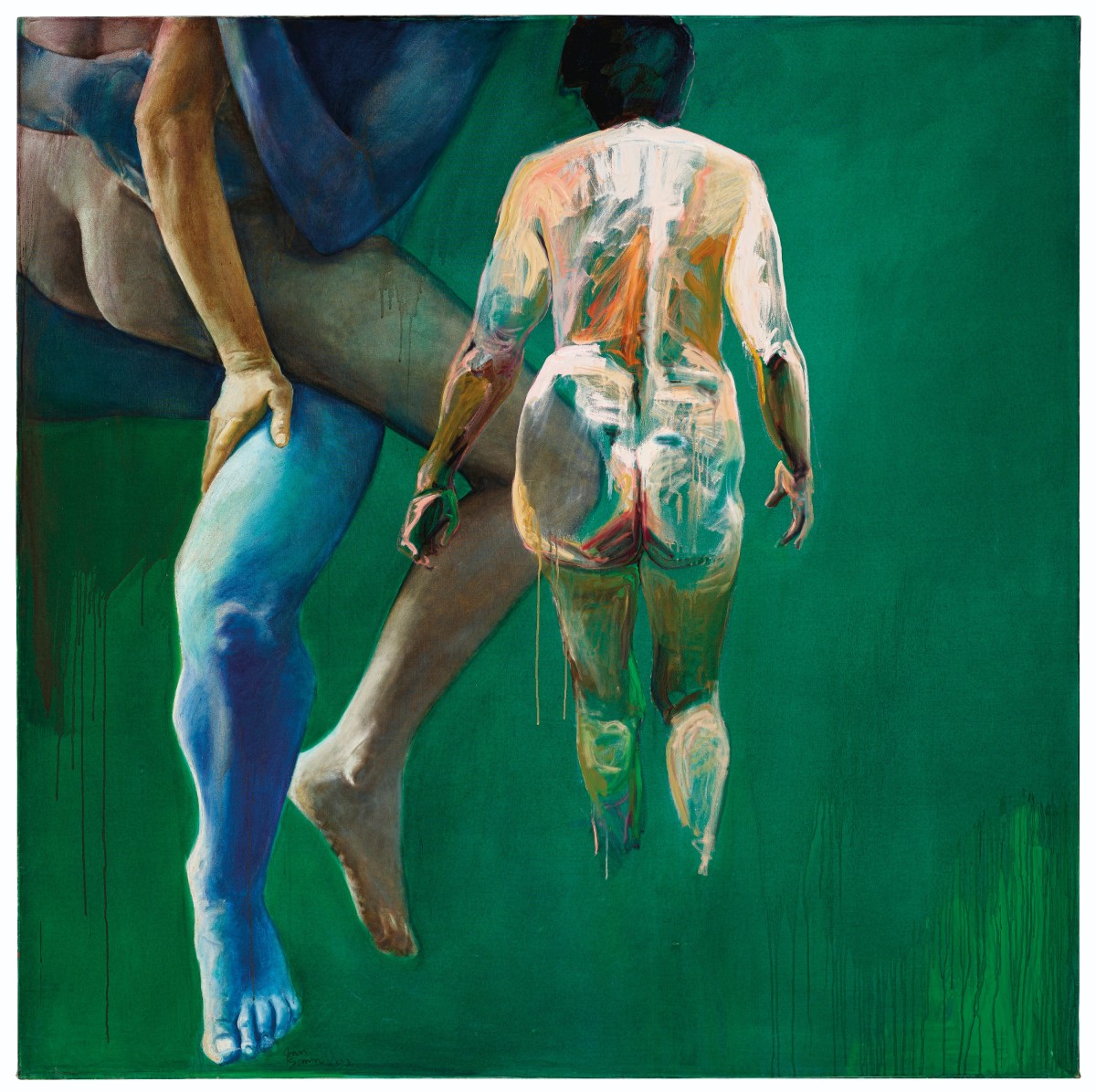

MG: What about the overlay paintings? They kind of confront already this subject. We have this earlier sexual painting, and then there is a figure of someone else, older, entering the picture.

JS: I used a couple of the early sexual pieces, and I threw an image of people in the locker room over that. It was a superimposition of one image over the other. I liked that because it gave a sense of time, memory and emotion. It’s the way we should have experienced imagery in a certain sense, it’s in memory, and then it’s the present and the past.

MG: What about the other series that you made earlier, The Echoing Images?

JS: That was one of the groups of paintings where I was trying to integrate my abstract gestural work with the realist way of working. I was playing around on the paper first and did some collage with images of the body; I used self-images taken from photos and xeroxed; working with one image that was realist and one that was expressionist. Putting them together in one context would give me, again, that sense of two mind spaces, so to speak. More than one looking at, and one over how you’re thinking about yourself, and so, that was a part of the conceptual way of developing those ideas.

MG: You’ve stayed in the territory of painting all the time. You made great paintings. What was the reaction from other painters or painters’ groups in New York to your work?

JS: I think my work was always respected as being from a very good painter. The problem always was that I didn’t fit anywhere in terms of what was being done in New York. For the conceptualists, the work was conceptual, but it was painting. Painting, of course, was dead for them. It was told to us over and over again and, of course, it’s still alive. Figuration wasn’t something that anyone wanted to look at, at all. My work didn’t fit into a pure realism like the Photorealism; it was really too gestural for that, but it wasn’t gestural enough for the Abstract Expressionism.

MG: I assume that such an attitude made your work difficult for the art system that tends to be very exclusionary if something doesn’t fit into a current discourse.

JS: Being that kind of artist that doesn’t fit anywhere, it was very hard to get critical traction or anything else. Somehow or other, my work was always reviewed although I was without a gallery for many years. The work never sold much.

MG: How did you survive financially?

JS: By teaching. I was a full professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

MG: Did you enjoy teaching?

JS: I like to teach, and the students were a turn on. It made me feel like I had a connection to the world; I wasn’t just alone in the studio. I didn’t have to worry about taking risks. I could do whatever I wanted on the canvas. I never worried about selling paintings. I had enough money to live on. It was a perfect solution. Teaching was two or three days a week, so I could still do my work and be who I am.

MG: What do you consider as the breakthrough moments in your work?

JS: Well, the curator Helen Molesworth did a show at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, in 2008. There were three of us: Lee Lozano, Sylvia Plimack Mangold and me. That was a major show, and Helen was a very respected curator, so that was important for me.

MG: It was the moment when your work had been “rediscovered”?

JS: That was the beginning of a whole new interest in the work, but it was gradual. I think that some of it had to do with the fact that a lot of the art historians who had been educated by feminists, started getting jobs all across the country. Consequently, both curators and art historians were showing the slides of the work. People knew my work – I never understood really how they knew it, but they did. People would come up to me and say, “Oh, I love your work.” I’d say, “How’d you know it?” They say, “Oh, I saw it in my art history class.”

MG: Amazing.

JS: It is amazing.

MG: One of the objectives of the feminist program was to break up the artistic canon, and actually you did it. It must be very rewarding. The artistic canon in 2020 looks completely different than fifteen or twenty years ago.

JS: That’s right. I really think that those art historians haven’t got enough credit for what they did. They did bring the message out, young women saw it and responded to it, and I think that was really important. My work was always written up a great deal in all the feminist writings, the women’s art journals and all of those magazines. These people always supported my work, so I think it was cumulative. Also, I think that the work was very relevant to what was happening in young women’s lives in general, because, across the country, women started getting educated and entering all of the professions. Those images felt real to them. They were relevant to what their problems were, and I think it just happened that way. It’s really hard to know how or why. The crucial thing was when I joined Alexander Gray Associates.

MG: The NYC gallery you have been working with since 2011. Which gallery was relevant for you before that?

JS: Mitchell Algus’s was a gallery that just found people whose work had been important at a particular time and then ignored. He didn’t worry about selling. He’s run this little gallery, a very interesting guy, always brings out these people and they get written about because the writers like what he does, and so that was a big thing. Then Gober did a show at Matthew Mark’s gallery in 1999 that used my work.

MG: Did you know each other?

JS: I didn’t know him. He called me, came to my studio, and asked me if he could use the paintings. He used the self-image paintings Intimacy-Autonomy and Touch in the show at Matthew Marks’s, which is a very famous and important gallery, and he was – of course still is – a very important artist. It was very important for me that those pieces came out. That was a breakthrough also for my work coming to the fore again, being seen again.

MG: What about your writings?

JS: I never considered myself a writer, but I’ve written a piece from time to time. I started an anthology of women’s sexual art that I had done the introduction for and had a few writers to contribute pieces too. I did a couple of my catalogue introductions and I’ve written on one or two other artists for various publications; nothing very polished. There are a few key pieces; one of them is the introduction to the book that was never published. Although they paid me for the contract and all, they just said, “Oh, well, feminism is over” and they didn’t want to go ahead with it. So that fell apart, but I still have the piece and it’s been reproduced in one of my catalogues. There is the essay on the curated show I did at the Brooklyn Museum that was published on the poster, but nothing important; I’m not a writer.

MG: I read two very interesting pieces you wrote on Lisa Yuskavage and Jenny Saville; you are not afraid to take a critical standpoint.

JS: Yeah, I won’t write unless I have something to say. That’s the only thing that makes me write, because, as said, I don’t consider myself a writer.

MG: Wrapping up, you are in the top form, your work is excellent, you’ve been continuing painting, you managed to contribute to changing of the canon and to be an inspiration for a lot of women, which I think sounds great.

JS: Well, look, until this terrible period that we’re in now came upon us, I felt, well, I’ve made a contribution. I’ve been lucky enough to be alive and have my work validated culturally, so I’m happy. But now everything else seems irrelevant in a funny way.

MG: Most probably we’ll be back to normal one day. You said in the beginning of our conversation that you still think in abstract terms about painting. Will we see pure abstract paintings from you next years?

JS: I don’t know, you can never tell. I work in series; I work with one idea for a while and do ten-twenty paintings depending on how long it lasts. Then I’m tired of doing that and I look for what happens next. I’m at that place right now of what happens next. I don’t know what I’ll do. I’m getting a little tired of looking at myself [laughs] and I don’t know if I want to deal with the next era of aging at this point; it’s getting a little late. I’m eighty-seven years old, I don’t know if I want to expose myself anymore.

MG: That’s really challenging.

JS: As I got older, I said, “Can I do this? I don’t know. Can I really do this?” But I did.

MG: You said, very beautifully, that your work is about painting an icon and not about the narrative. How do you know that the image has the iconic quality?

JS: Well, it’s just about my eye, I guess. I take photographs, I put them in the computer and crop. When I’m cropping, that’s how the image becomes the icon, for what I leave out, where I focus. I refine the image, then I print it, and so I can see really how I formulate that.

MG: Using photographs and computer as instruments to create the basis for the painting.

JS: That’s the process. The computer and the photography became a tool that I use.

MG: Are you a prolific painter? Are you working at the same time on several paintings?

JS: No. I work one painting at a time usually, but I keep them around and then go back and forth a little bit. But I basically work one painting at a time. I’ve put out an awful lot of work in these last few years, that’s part of why I’m a little tired.

MG: Many thanks for the conversation.

JS: Thank you.

All images courtest the artist and Alexander Gray Associates and Artists Rights Society.

Photo: Emiliano Granado