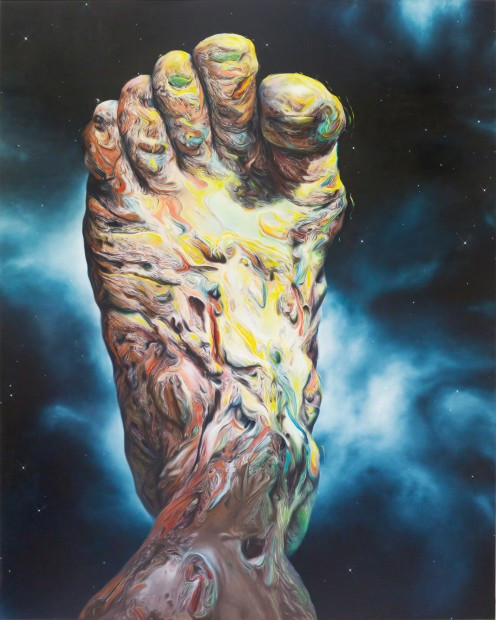

Glenn Brown

Published: March, 2016, ZOO MAGAZINE #50

MG: The first painting on your website dates from 1988 and looks completely different to what you are doing now. What did you think about painting at that time?

GB: In the late 1980s, neo-expressionist painting represented by artists like Julian Schnabel, AR Penck or Georg Baselitz was very fashionable. At the same time though, there was the other school of painters like Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter, who were addressing the ideas of photography and the printed image, and who I considered to be much more profound in dealing with painting than the artists throwing paint around. It seemed to me to be very difficult to make relevant figurative painting that didn’t acknowledge photography.

MG: You studied at Goldsmiths in London alongside artists who later became known as the YBA[Young British Artists.] During that time painting was not considered very relevant…

GB: I started my Masters in 1990 at Goldsmith. London still seemed to be a backwater – it was New York and Cologne that were the major art cities. The notion in the air was that painting was dead or at least unimportant. Certainly at Goldsmiths, video, photography and installation were what seemed of relevance. But maybe because painting was not looked at in the way I wanted to look at it. I have always wanted to look at things or thoughts that are neglected or overlooked.

MG: Did you always want to be an artist?

GB: The first course I attended was a so-called a foundation course, which was a one-year study of design, painting, sculpture or photography – if you are not sure what to do you will have a year to find out. I did a lot of life drawing at that time, which in a way was antiquated. I thoroughly enjoyed being in a class filled with all these plaster casts and realize then that I don’t want to do anything else in my life.

MG: I’m thinking about your 1991 painting, The Day the World Turned Auerbach. This early painting has the main characteristics of what I would call your signature. Was seeing Auerbach a moment of revelation for you?

GB: Soon after I started at Goldsmiths, I was brought together with three other students on a course because we were all doing ridiculously similar work using photography in terms of painting, comparable to Gerhard Richter. The head of the course, artist Gerard Hemsworth, said to us: “Why do you paint? Why do you not simply take photographs? You are far more interested in the mediated image.” My way of answering these questions was to stop painting for a while and do something else. I thought: “What do I paint if I don’t paint photographs?” Richter was a model that became more like shackle. I was chained down by his sense of painting. As a painter he uses paint but he doesn’t deal with painting in a traditional way, he doesn’t deal with composition of color or form. And then I discovered: I will paint paint. This is the most stupid and obvious answer conceptually, but it was the right one at the time. Looking around the person who was using the thickest paint layers in painting was Franz Auerbach.

MG: So choosing Auberbach was a conceptual and not an emotional decision.

GB: It was a very conceptual decision. I used to make painting based on the photographs of the moon surface, which were flat surfaces with undulations on it. Since a painting is fundamentally a flat surface with undulations of paint on it, it was very easy for me to step over from the moon paintings into painting paint. It fitted into the conceptual model.

MG: You mentioned several times that post-structuralism is a very important concept that relates to your work...

GB: French philosophy was very important at Goldsmiths at that time. It was very exciting to think about art in terms of a language: to break visual codes down and to try to understand what you are doing though philosophy rather than making nice paintings. While structuralism suggested that there was one language, post-structuralism suggested there are many languages that are joined together. Art is just another language you need to understand to be able to communicate.

MG: Derrida proposed that the texts refer to themselves, not to the reality that the texts attempt to describe. Did you think in the same way about paintings? That paintings actually communicate with other paintings but not with the outside world?

GB: In some sense, exactly the opposite. Painting was tied to film, theater, photography and all other possible languages that were connected to each other. That’s why Deleuze and Guattari became so important to me because they came up with their idea of the rhizome, a structure in which everything was connected to each other.

MG: If you think about painting as a language that you need to learn in order to understand, this means that the painting – in relation to your case — is not easy to read.

GB: Nobody can really understand all of the languages all at the same time. You can bring your knowledge of other languages into the painting, such as architecture, photography and tools that interchange with other disciplines. My audience doesn’t necessarily need the knowledge of painting to enjoy them even though my paintings very heavily reference European art history.

MG: So you don’t mind if a viewer sees your works without understanding the historical art references? That they appreciate them mostly in terms of beauty and decoration?

GB: I would like my work to be beautiful and decorative. Both are complicated terms that can be very challenging. Fashion is certainly very good at claiming the idea of what beauty is. If contemporary fashion designers were just doing something that has to do with pleasure, symmetry and perfection, it just wouldn’t work. The contemporary audience wants imperfection; they want things that are purposefully awkward because this makes you think.

MG: Do you think about the viewer when making a painting?

GB: Absolutely. I have a lot of works in the studio because I’m working on all of them at the same time. I’m very good at starting a painting but not very good at finishing them. My friends – artists and non-artists – look at the work when I’m making it and criticize them (“You could make this blue; you could change this; you made this decision that doesn’t seem right…”) I listen to what they say and I change the work accordingly or not. This process is very important to me. I have never made a painting just by myself.

MG: Why not?

GB: Two heads are better than one. You could fall into bad habits or take too easy routes; it is always good to have as many views on something as possible. You don’t need to listen to it, but you should know.

MG: This attitude relates to your ideas about originality.

GB: I think that originality is impossible to achieve. As I said, we need a language in order to communicate and that means that the structure needs to be borrowed, otherwise it means nothing. To be an artist and to be understood, you have to borrow from other artists or the culture; you have to take the ideas and to put them together and place your work in relation to what has happened before you. I can’t be totally original otherwise I make totally irrelevant works.

MG: I do understand how relevant this concept is for your work but I’m very curious whether deep inside you don’t consider yourself to be a brilliant and original individual.

GB: I don’t think about myself as a genius. It would be meaningless because that involves lifting yourself outside the framework and environment you are in, which is so important. Artists I talk to, people I have conversations with, they all change the way I think. I do honestly believe that I’m a part of the structure.

MG: One of your paintings that plays around with Rembrandt’s work carries the title Joseph Beuys. Beuys considered himself a shaman; he wanted to heal the world and was a very charismatic person. Why did you want to engage with him?

GB: I think the word shaman is very important here: Shaman is a conduit; it is something that information passes through. Shamans don’t have a sense of being original but present ideas to a society in a different way, which my painting Joseph Beuys does as well. It is a son of Rembrandt in a fanciful costume – you might not even be able to tell whether it is a boy or a girl. It has a green face that looks very peculiar. In many ways, it is just the opposite of how Joseph Beuys wanted to present himself. In my version, he is not the serious intellectual who is going to heal the world, but a shabby spoilt child wearing gold earrings. Maybe that’s what was going on all the time in the art of Beuys; maybe that’s the real him and all the rest is what he pretended.

MG: The title is essential to understand the work.

GB: Many of the titles I use present an idea opposite to what is actually happening in the painting. They are there to make you challenge your notion of what a painting is. So many of my paintings are upside down — again to challenge you — to make you look at something completely afresh as if you haven’t seen it before.

MG: For your paintings you very often use works of Old Masters. I was wondering whether it is a kind of aemulatio, the Renaissance idea of competing with the other masters to show that you are better.

GB: I don’t believe that the world is getting better; I don’t believe that art is getting better either. I think that is just changing. I’m not trying to make better versions of Auberbach or Rembrandt. I’m just trying to make something that is different and relevant today in the 21st century in the view of what I think of the world; again, being a conduit in order to put together ideas in a new way, which are not necessary new ideas.

MG: Have you never enjoyed the fact that you are doing something better?

GB: I want to make works as good as I possibly can. I may be competitive with my peers but I don’t claim that I can make paintings like Rubens, Goya or Titian.

MG: Although you use existing images as the basis for your paintings, you need to make a selection from billions that are available. How do you choose, especially taking into account that you make so few paintings?

GB: I read a lot of books, I go to museums, I see as many works as I can in different formats, I look on the Internet. Certain images stand out so I will take notes about them. The digestion period from taking notes to starting painting can be one or two years but then I know that the images have relevance. What surprises me is that I often will have an idea for a painting and search a particular image that fits into my concept. For example, I know that I want to paint a big blue painting so I will try to find a subject matter that fits in with a blue big painting. I also like that many museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam have digitized all their images now, so I can get wonderful high-res images of virtually all works from their collection.

MG: The majority of your audience sees your works for the first time, and maybe the only time on the Internet. This means that they will never notice what you do with the paint and never experience your concept of paint – which looks like very thick impasto but in reality is very flat. Does that bother you?

GB: It does bother me. Sometimes people come to me and say: “I like your paintings, it’s so nice that somebody can make a gestural painting in this age.” So I’m saying that they missed the point. I do make objects that have to be seen in the flesh. I love the technology of painting: it is so precise, the color is very defined: no printing or no computer screen could ever reproduce this. Every other medium seems so poor in comparison to painting and the beauty it can have. I like it so much.

MG: The irreproducible quality of painting guarantees its future…

GB: Well, the 3D printing might come along and change everything, but not for the time being.

MG: Why has painting become more accessible in our time?

GB: It’s been very interesting for me to see how contemporary art has changed hugely in London in my lifetime. It’s been fantastic to watch the public appear from nowhere and fill museums like the Tate Modern or the Serpentine Gallery. The audience of contemporary art has quadrupled in the past 20 years, which I think is great. Previously, museums were often the boring places where academics went and that didn’t really have any impact on contemporary culture at all. That’s changed. We seem to be living in a wonderful time for art.

MG: The popularity of contemporary art can be credited to more entertaining programs in museums and also to the explosion of the art market in the last 15 years. People have very different reasons to enter the art world. What is the main reason for you to be in the art world?

GB: I make paintings, drawings and sculptures for people to see. If nobody saw them I’m not sure that I would like to make them. I want to comment on art history and major issues such as what does it mean to be a human being, how do we think about life and death, what is beauty. I want my comments to be relevant and to affect the audience; I want their feedback. Some people might see my work as extremely ugly, others might think it is extremely beautiful. Sometimes it looks very modern, sometimes very old-fashioned. Making works that have opposites in them creates a certain dynamic. I make paintings that have a lot of details in them so people will come to look very closely and then step back again. You are animating somebody by moving him around and making him think.

MG: Art as medium to make people think…

GB: If you are left with many questions after looking at art, that’s what counts for me. It is like seeing a film and worrying what would happen to the main character in the future. The illusion becomes mixed with the reality but it changes your perception of reality and how you relate to the world. That’s what a good exhibition does: you enjoy looking at the works but you walk outside and you will start seeing elements of it somewhere else.

MG: Let’s speak about the current artist model. You have been criticizing the ‘macho model’ by making the gesture fake and the originality questionable. What do you think about the current popularity of the macho painters who are extremely in vogue? Don’t you think that art is a territory that loves divine inspiration and grows on the soil of myths?

GB: I kind of like those big macho gestures as well. I fall for them as much as anybody else does: you can attack them and compliment them at the same time. When I make what appear to be big gestures, which take weeks to paint, I get enjoyment out of it and the audience gets this sensibility in my work as well. Georg Baselitz started to make remakes of his own paintings: he cut, put and remixed them together and actually criticized his own sense of self. Such paintings can be ironic, gestural and romantic all at the same time. Julian Schnabel is very good at this; you are never quite sure what he means, whether a work is meant to be romantic or ironic.

MG: Another concept used by you is appropriation…

GB: In terms of appropriation, the artist who influenced me the most was Sherrie Levine. It was her who first let me realize how wonderful it was to see a piece of work and not quite know what you were looking at — a photograph or a photograph of a photograph. It was a conceptual notion that was bewilderingly fantastic.

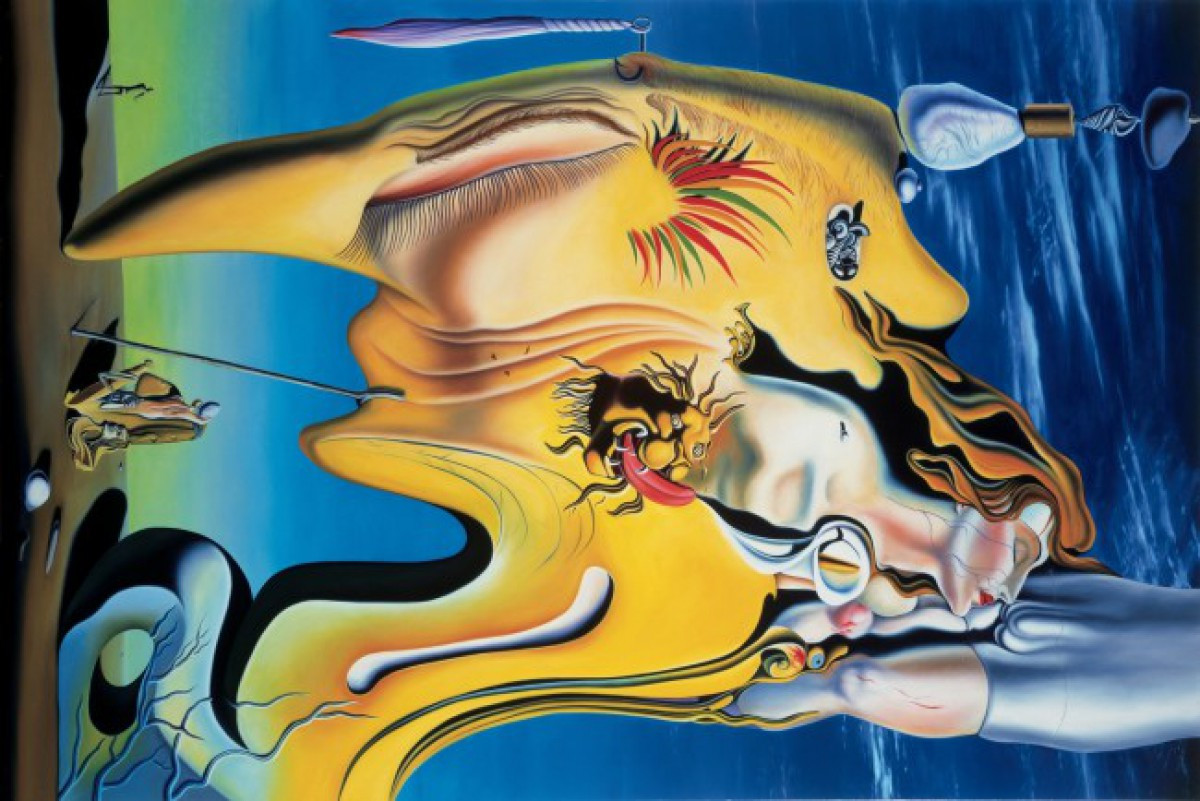

MG: You have subsequently been mixing the idea of high and low art. You used images of Salvador Dali, covers from science-fiction books and titles of pop songs. Do you believe that the division between high and low can be lifted?

GB: Will you put Dali in the high or low art category? I’m not quite sure. There is nothing better to listen to than a piece of pop music then realize how profound the lyrics are and how complex its philosophical ideas are. Similarly, an awful lot of what is considered high art is actually poor and simplistic in what it represents. I think that people will always claim that something is more important than something else.

MG: Your art is visually appealing and conceptually demanding. It this a recipe for high art?

GB: I think there are lots of recipes and a lot museums have different ideas about what high art is. Lots of artists present supposedly rigorous political sociological notions but with closer inspection they may be at a level of an 8-year-old. Conceptual art could be very guilty of being simplistic.

MG: How important are museums in detecting good art?

GB: I think museums are wonderful places: they can challenge, educate and entertain all at the same time. I think art should be entertaining. A lot of museums have probably a pretty good take on how the audience is and how to challenge them. Tate did a wonderful job in challenging the whole role of art, although they tend to think that performance and video are more interesting than painting at the moment. They are probably right.

MG: From the institution to the market, your paintings have become very difficult to acquire and very expensive to buy.

GB: It partially reflects the fact that I make very few paintings. I would like to make more of them but I can’t make them any quicker because I don’t want to produce works I’m not proud of. It takes hundreds of work hours to make a painting, figure out whether it is working or not, repaint some areas, change them… It is a huge waste of time but in the end it is the only way I can create something. The painting is almost a by-product of a complex creating process. People are paying a lot of money for them, which wouldn’t be the case if I could paint 40 paintings a year. In an ideal world, I wouldn’t sell any of them but keep them and lend them to people — so that people could show them.

MG: Do you keep any for yourself?

GB: I do because I can lend them to exhibitions. Many of my paintings have spent most of their time on loan to different places in the world, being shown and being seen. I want them to be seen by as many people as possible.

MG: Are you surprised by your success?

GB: Of course. I’ve been very lucky. The art world is very fickle and the art market is very fickle – you can be celebrated one moment and then considered to be the most old-fashioned artist. You never know how long it lasts.

MG: You are turning 50 this year. Do you consider yourself as a middle-aged person now? It must be a strange idea.

GB: Very much so. It gives you a very different view of life. When I’m comparing myself with the artists from the past, I think that maybe your best years have been in the past. It is very interesting to see that a lot of artists made wonderful works in their 20s and in their 30s, but by the time they were 40 their work became rather dull and boring. There are not so many artists who by time they get to 50 have made the best work.

MG: Does it scare you?

GB: I enjoy being older. When I was younger the world was full of problems and I was full of agonies about whether I was good enough. The older you get the more you realize problems are not so important and you learn to enjoy life more. You have more experience in life. As an artist, I have seen thousands of paintings; I enjoyed thousands of things. When you see something good, you really know it is good; there is no case of maybe. The hit you get from seeing something fantastic is far deeper and more complex than when it was when I was in my 20s or 30s.

MG: Are you also wiser?

GB: Hopefully.

MG: Can you give me an example?

GB: When I see my work from the past and I see the work that I make now, I make fewer mistakes, I know how to solve problems. I know how to present myself in a way that is coherent and more meaningful than I did years ago.

MG: What about your private life? This is a subject you try to avoid all the time. Is this deliberate?

GB: For 15 years I didn’t allow anybody to take a photograph of me because I didn’t want anybody to know what I look like. I considered it irrelevant. It was a time when artists like Damian Hirst and Grayson Perry used their public persona as a very important element of their work. I thought that there must be a different way because it seemed to be a bit too easy in the end. I wanted to do the complete opposite.

MG: Did you go to your openings?

GB: I did, but if somebody asked, “May I take a photograph of you?” I would say, “I would rather you didn’t,” which was sometimes funny. Anyway, now I decided to allow photographs because I’m nearly 50 (laughs). There is an English author called Julie Burchill, who writes for The Times as a cultural journalist. For about 20 years, the photograph that started her columns was one that was taken when she was 18. It was very funny when I actually met her for the first time because it was not what I expected her to look like or to sound like. She got to a stage of mind when she said it doesn’t matter any more, and you can relax after a while. You play, you can finish the game, you don’t need to carry on to the bitter end.

MG: The lack of information about your private life used to be a part of your concept of being an artist in the public space.

GB: Yes. I like to be a conduit of art to pass through, the conduit to art history. I like the mystic idea of being invisible to some extent.

MG: What about religion? Religion is very present in your work, at least the religious sensibility. Are you a religious person?

GB: I’m an atheist so for me it is a concept, but a really important one. I wouldn’t say that I’m a spiritual person; I’m fascinated by why people find spiritual realms so important and why people need organized religions as controlling mechanisms in their life. It intrigues me that people fall into these tricks so easily. I think religions are like fairytales; they are very interesting and you learn a lot from them but don’t take them as the absolute truth, because they are just fairytales written by people who tried to help or to control the world.

MG: How do you see your work in the future? Do you expect big changes?

GB: About a year and half ago I started drawing really seriously, which I have never done before. In the past I was telling others that drawing is very important, that it is the skeleton of the painting and a structure that holds everything together, but I wouldn’t do it myself. In the last two years, my work has changed enormously; I got carried away by drawing.

MG: You stopped painting.

GB: I did. I wanted a new challenge and my challenge was to make drawings. I’m very dogmatic when I decide on something.

MG: Don’t you miss making paintings?

GB: Not at the moment. I’m still too fascinated by black and white and line. It is all about the line at this moment and I can’t multitask. I’m sure that I will go back to using color because I love the sensation of what color can do. Maybe the drawings will slowly turn into paintings…