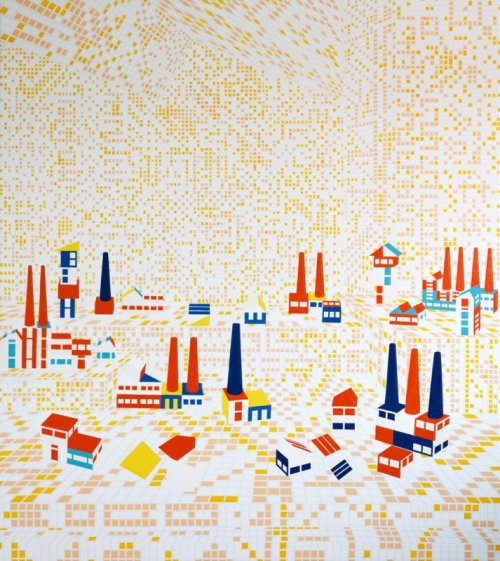

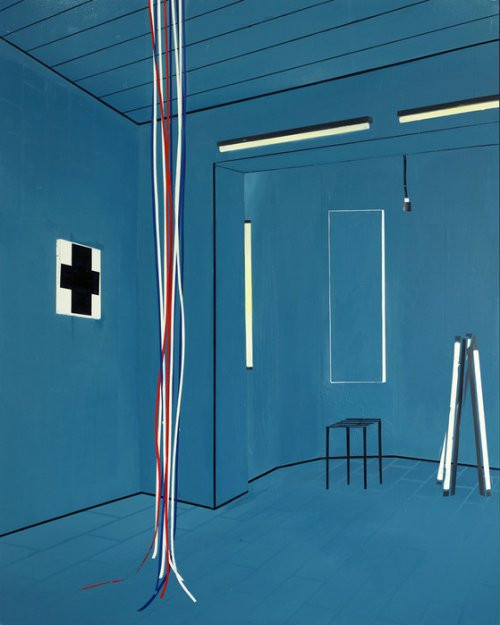

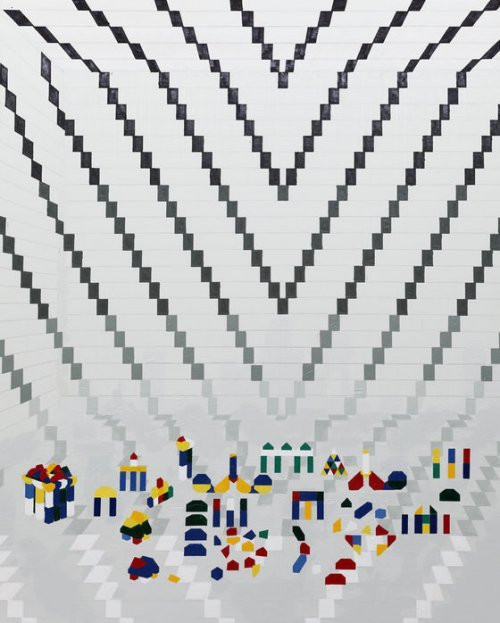

Farah Atassi

Published: May, 2013, ZOO MAGAZINE # 39

The painter Farah Atassi is currently working at her residence and studio in New York. Born in Belgium from Syrian parents and raised in France, Atassi combines various cultural legacies and formal approaches in the medium that she loves most: painting.

Marta Gnyp: Why are you so fascinated by modernist ideas about painting?

Farah Atassi: It is probably my nature: I like efficient and direct painting. I like the idea of painting in a very simple way and using simple forms. The modern functionality model is very close to my way of working – the way the images appear clean while nothing is hidden. I like simple, geometric forms; I like straight lines. My master is Fernand Léger.

MG: Your geometric forms and straight lines don’t result in abstraction though.

FA: I’m more sensitive to figuration. Which means that I don’t want to paint abstract but I don’t want to be too narrative either.

MG: How do you construct a painting?

FA: For me it is very important that the construction of the painting represents a space, although the point of departure is a grid and the flatness. I want to elicit a consciousness about space. In a way, it is a contradiction, since I’m using various effects to create depth and on the other hand, I want the viewer to be aware of the flat surface.

MG: In your new series you refer to the modernist medium specificity that was heralded by the art critic Clement Greenberg in the 50s and 60s. He proposed that each medium should limit itself to the qualities specific only to this medium, like flatness in the case of painting. Do you try to investigate the limits of this thinking again?

FA: Yes, I confront these ideas with the depth of perspective, expressionist forms and ornaments. At first look, there is this immediate, clear image in each of my work but then everything gets subtler when you discover the surface of the painting, and through it, you discover the process of making.

MG: What do you want to achieve?

FA: The core of my painting is to put contradictions together, to experience the fictive space in the work while being aware of the surface at the same time.

MG: You are a painter; you don’t use any other media. In this sense, you are a very traditional artist.

FA: Painting is all I like. I’m passionate about painting.

MG: Are you interested specifically in the modernist period or do you have other interesting cases from art history? Did you ever imagine relating your work to painting from other periods?

FA: Absolutely. Giotto’s oeuvre has a lot of aspects that I explore in my work as well. Beautiful. So many contradictions! Since perspective didn’t exist in his time, he had to use volumes to produce the effect of depth. In this sense, I feel very close to Giotto. Also, in his use of clear and simple shapes.

MG: In your works, the perspective is very important.

FA: I never really learned about the perspective. Once I started to apply it, it turned out to be very easy to do. You need to decide where you want to have the vanishing point – low, high or outside the canvas. I have been using them since 2008. Now I know exactly the effects of using different variations of it.

MG: In the past you painted interiors that seemed to be more realistic.

FA: That’s correct. The spaces now are less narrative. In this period, I work on the paradox of modernity.

MG: What are the other themes that are important to you at this moment?

FA: I think I have always been interested in folklore, especially Russian and German. One of my favorite films is Die Nibelungen by Fritz Lang, which has many elements stemming from German folkloric expressionism.

MG: Have you always been working in series?

FA: Yes.

MG: Do you always work with the same format?

FA: Always approximately 200 × 160 cm. I like this format because it is a human size so you can relate to the painting.

MG: How long does it take you to prepare a painting?

FA: It depends.

MG: The last half-year, you have been resident in New York. How does this city influence you?

FA: I will probably know better in a few months. I’m thinking a lot about American modernism and European avant-garde, but I’m mostly working in my studio.

MG: How come you became an artist?

FA: I knew very early that I wanted to become one. I was always drawing and painting a lot. Actually, I decided on it when I was very young.

MG: Did you go to an art school in Brussels?

FA: No, I was born in Brussels but together with my parents, we left Belgium very quickly and moved to France. I went to Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and then I participated in an exchange program with the Art and Museum School in Boston, so my first American experience was already 10 years ago. I graduated in 2005 and it took me three years to be prepared to show my work. I started only in 2008.

MG: It must be a difficult period for most young artists who graduate, when there is nothing, no gallery, no collectors, no protection from a school: you simply have to start working.

FA: It is a very difficult period. Because as you said, nothing is happening but also I didn’t feel well prepared. I as an artist wasn’t ready and my work wasn’t ready to be shown in a gallery.

MG: How did you survive?

FA: Sometimes I sold a painting from the studio and sometimes I worked in a shop. My Paris studio was very cheap to rent so it was possible for me to concentrate on working. In 2008, I started to show my work to a bigger public, initially from my studio. These three years were very important to make myself ready.

MG: In 2010 you started to work with a gallery. You were invited to other group shows and your visibility became very strong. Your works landed quickly in collections of important museums and you are considered one of the most promising young talents in France. There is an increasing interest in your work. How does it feel?

FA: Maybe it is strange to say but it feels natural for me. If it didn’t work it would be catastrophic for me because I’m a painter and I don’t want to do anything else. My life is to be a painter. I highly appreciate my luck and think it is extraordinary what is happening to me but it had to be like this.

MG: You were born from Syrian parents. Do you think these Oriental roots helped your career because people who are interested in your art consider you more exotic, with all due respect?

FA: I don’t feel like a French painter. I don’t belong to the French school. I’m not French, I’m not Belgian and I’m not Syrian, and I’m very happy about it. Some people need to belong to create their identity. I don’t care, and I don’t belong. I’m very happy to have this freedom. I don’t belong to any country and I don’t think my painting belongs to any school.

MG: Why did your parents go to Belgium?

FA: To study and then they stayed.

MG: So in brief, there is a Syrian connection in you but not an obvious one. What about your preference for ornament?

FA: Syria is not really present in my life. I have never worked there, I don’t speak the language, but subconsciously, my emotional part is Arabic.

MG: Is this what makes painting interesting to you, to discover all the time limits and possibilities?

FA: It is very interesting to work on a subject and then discover its limits. Then I have to accept it. In all paintings there is a decorative part. I have to take this aspect into account; I myself have to find dialectics between my decorative part and the rigorous interventions with models.

MG: How do you experience your age in relation to your work as painter?

FA: It depends how you see it. 32 is not very young. When I was in Paris, I didn’t think about my age. Since I’ve been in America, I have faced the idea of age. 32 here is no longer young. All is relative.

MG: What is your ambition? Every now and then the medium of painting is declared dead.

FA: I want to show that young artists can find new approaches and be passionate about painting. I know that I will do painting my whole life, because I believe in it. I want to show that it is possible to make great paintings in our time.

MG: Does being a woman artist make any difference?

FA: It does because all of us have to cope with very concrete questions about life. The man has, for example, more time to think about a family and social pressure. At 32, as a woman artist, you have to manage a lot more things at the same time. As a woman, I try to find a solution to be present and generous to others and at the same time, concentrate on work.