Damien Hirst

Published: June, 2022

Marta Gnyp: Let’s start with your most recent project, your exhibition, Veil Paintings, currently being shown at Gagosian LA. What struck me when reading the reviews is that even the most basic artistic act, which is an artist painting by himself, by hand, is in your case considered provocative.

Damien Hirst: Oh yeah, I just find that funny.

MG: Did you expect this kind of reaction?

DH: Not really. I’ve always made art myself and always used other people. Almost as soon as I could walk, I started getting other people to help me make art.

MG: There is no difference for you, whether you paint a work yourself or let someone else paint it?

DH: When I’m doing a series of works, I always paint the first ones. That’s what I have to do in order to show the studio what I want. But I don’t really see a difference. We live in such a multifaceted world today that using a single approach is very difficult. If you say, “I’m just gonna paint like this and I’m gonna make my work as art that reflects the world” – I don’t think that’s possible. That’s why I end up making paintings, sculptures, installations and videos – everything that I possibly can, because we’ve come to be constantly bombarded by a world that’s like that. It’s the visual language we live with.

MG: Your last project in Venice, Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, was more like curating your own ideas and production instead of making it yourself.

DH: To take a tiny piece of paper and a pencil and make marks on it is exactly the same as what I did in Venice – there’s simply no difference. It’s just organizing elements, it’s always art. It’s funny, because for years people have been saying “he doesn’t paint his own paintings.” To me, it seems like a silly debate. It’s strange to have it for art and not elsewhere; somehow people think it’s important, but I don’t think it’s important. You would never expect an architect to build his own house. Frank Gehry didn’t physically build the Guggenheim, which is very much his building – and I think art can work like that.

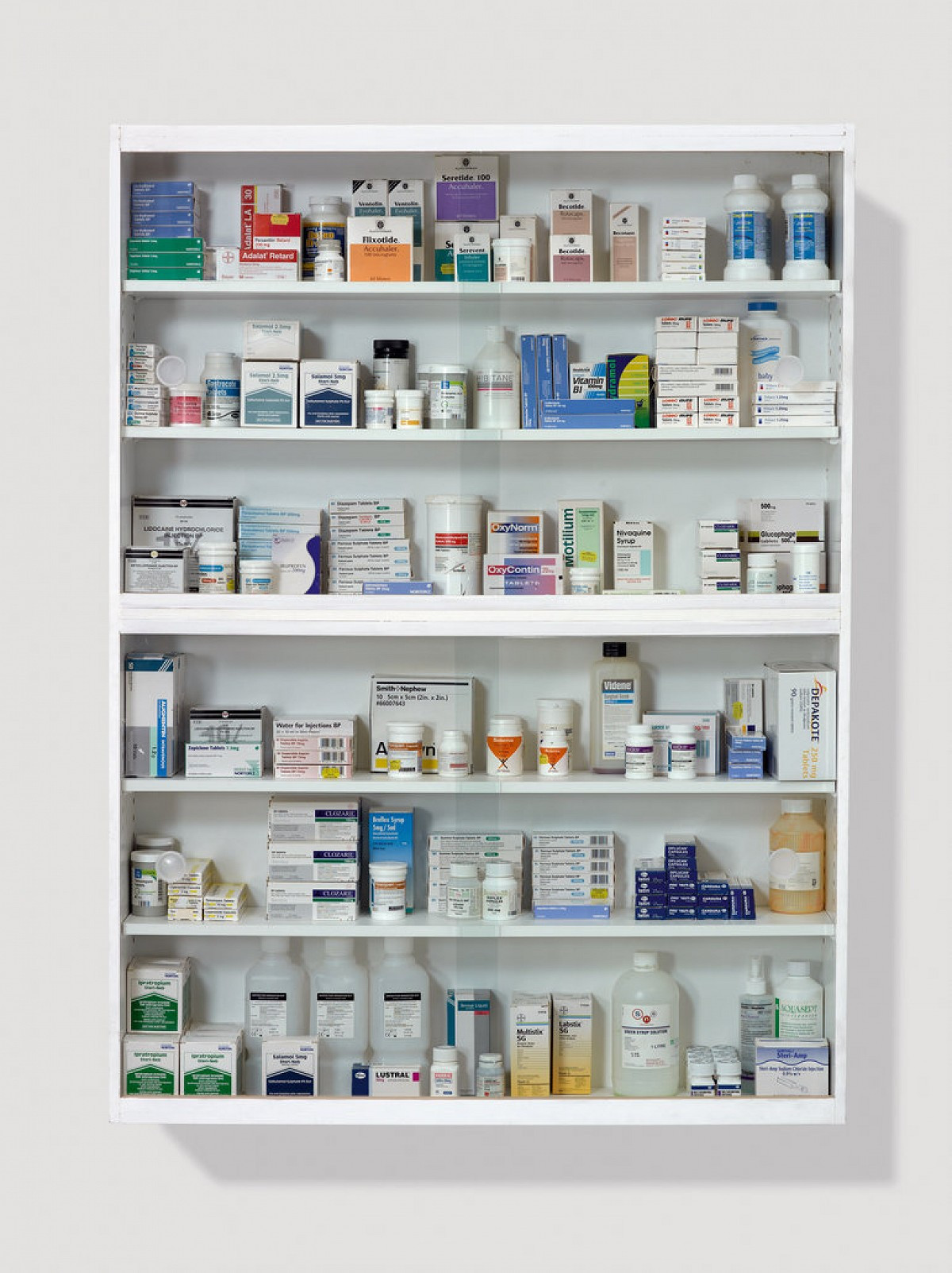

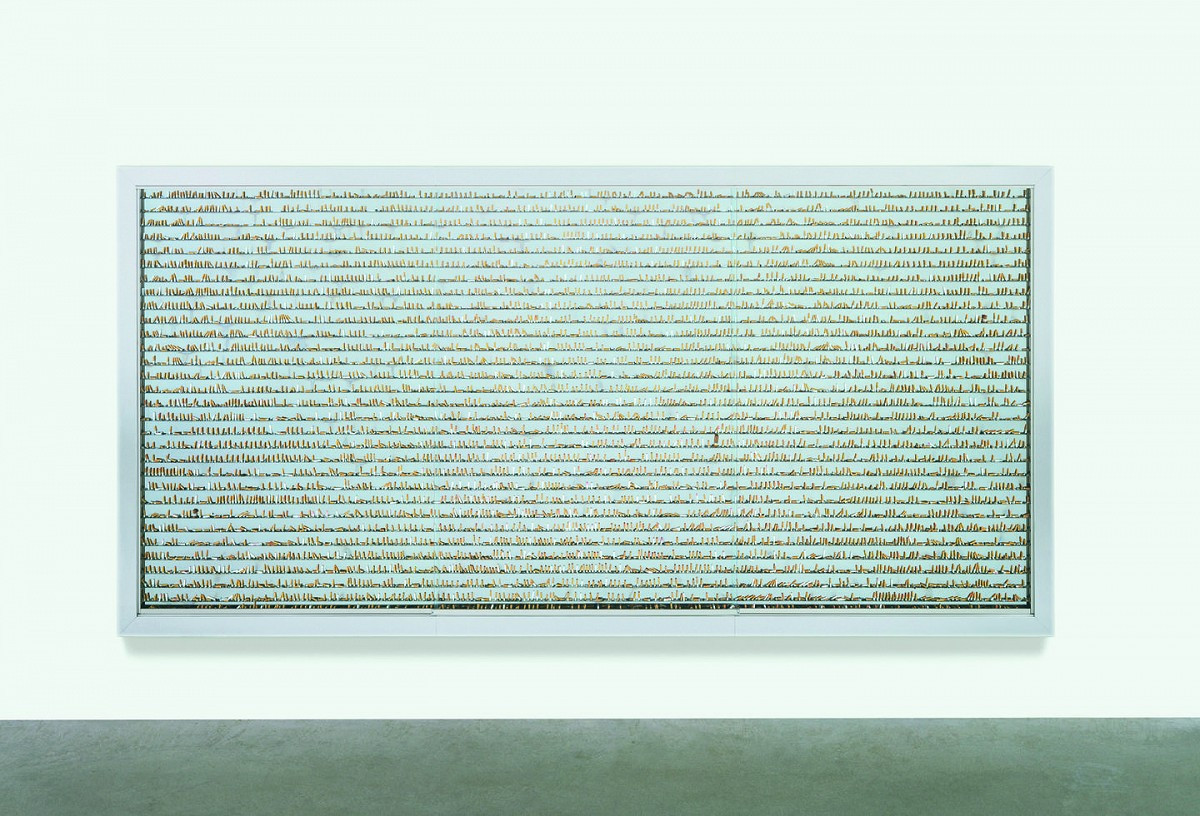

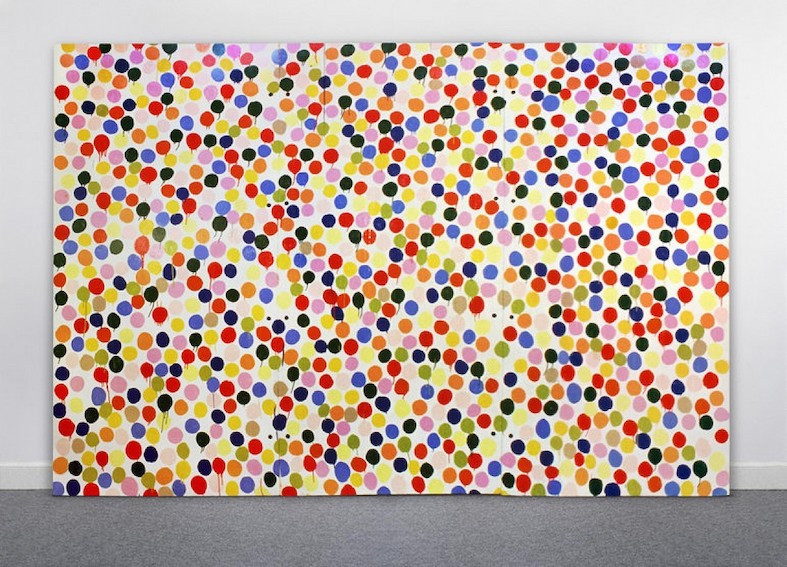

MG: If we you go back to the origins of your work, the core of your ideas was formed in just four years. Between 1988 and 1992, you created Spot Paintings, Spin Paintings, the Natural History series with animals in formaldehyde, the Medicine Cabinets. I wonder, were you aware at the time of this gigantic outburst of creativity?

DH: Yeah, but it wasn’t just me, it was also my generation. I had lots of friends who were making a huge amount of art as well. The thing we had most in common was the fact that we had nothing in common – and I think that was sort of acceptable. We all drank in the same bar and we all felt very comfortable with each other because we were all doing very different things. I think that makes sense, whereas maybe for other artists in the past it didn’t.

MG: You embraced difference as a part of the ideology of the group.

DH: Before I went to Goldsmiths, I was very aware that I had a lot of conflicting ideas and wasn’t sure which one to go with. I couldn’t really make decisions, so I was becoming inactive. Then, at Goldsmiths, I realized that it didn’t matter: I could just pursue them all. You could say that the guy making the formaldehyde works doesn’t really suit the guy making spin paintings, and it could become a little bit crazy. But I decided I was just going to pursue everything: I was going to make work from every idea that I had, even though the ideas looked conflicting.

MG: It probably took a lot of time to pursue all the ideas.

DH: The first painting I sold, I used the money to pay other people to make more paintings for me. I was selling a painting for 500 pounds and I still spent 400 pounds of that to pay other people to make more paintings.

MG: You must have been very convinced about your ideas.

DH: Only really when I started at art school. Don’t forget, you start painting and drawing when you’re very young. I was drawing from when I was around four, five years old. I only started thinking I could make a living doing art when I was at Goldsmiths and I just had to relent.

MG: From the very beginning of your career at Goldsmiths, you were a kind of entrepreneurial artist, a curator, and a very public person. We have models of this approach in the post-war art world, such as Andy Warhol or Jeff Koons, but your activity as an entrepreneurial artist was special in the European context. Was it a spontaneous decision or a consciously chosen attitude?

DH: I don’t really know. I don’t want to give Margaret Thatcher any credit but she was around at the time, pushing for people to do things themselves. There was the Prince’s Trust by Prince Charles. There was a big push in England saying, “Do it yourself.” There was also a lot of really great art at my art school. I worked for Anthony d’Offay Gallery, so I was looking at work by great artists like Carl Andre and then going back to my art school. I was thinking, the work done in my art school was at least as good and as confident as that of the gallery. When I was still a student in 1988, I organized the Freeze exhibition that had seventeen artists in it, but with the art world being the way it was then, there was just no room for something like that. I had to be entrepreneurial, if you want to call it that. It was just a really creative time with lots of exciting art going on and lots of friends all in the right place at the right time. I don’t know what caused it. We came out of a time when there was a lot of poverty.

MG: You just mentioned Anthony d’Offay. Were you an assistant in his gallery?

DH: I was like a backroom assistant sorting out paintings, hanging works, dealing with artists, moving things around, putting things in trucks – all that sort of stuff. When I moved to London, I didn’t have any money, so I got a job at d’Offay for three days a week: Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays. I was on a full-time course, but I managed to squeeze it in. So I was doing both – Goldsmiths and working for Anthony d’Offay at the same time.

MG: It’s quite amazing that you got the job as a student, because at the time Anthony d’Offay was probably the most important gallery in Europe.

DH: It was the most important gallery in the world. I was being directly influenced there – handling great art and then going to art school and back. I was backwards and forwards between college and Anthony d’Offay. There were always really creative people there, like Sadie Coles, Matthew Marks, Tanya Bonakdar; a lot of great artists like Gilbert and George and Joseph Beuys. I met Warhol there.

MG: Was this also the place that taught you how the art world functioned?

DH: It was more about understanding great art, I think. It was the first time that I was in direct contact with really great art: Yves Klein’s paintings, Carl Andre’s sculptures, Dan Flavin’s pieces, great Richters, Bruce Nauman. There was just loads and loads of great art around.

MG: In this early period, in 1990, you made the work, A Thousand Years, an extremely mature work for someone that young. Was it not intimidating for you to make such a profoundly existential work at such a young age?

DH: I don’t know. There were a lot of doubts when I told my friends at college what I was making and they started laughing at me. I like to get into a sort of punk rock position of not caring – you have to say, “I don’t care. I’m just going to do this.” I thought all great art was about important things. I was struggling with art that was about superficial things. The Spot Paintings felt a bit superficial, the Medicine Cabinets didn’t, but they were sort of my take on Jeff Koons’s Hoover pieces. For some reason, I just thought I had to make a piece about something really important; it just had to be about life and death and it had to be minimal. I was looking at other artists like Jannis Kounellis, who I loved. There was a great tutor at Goldsmiths who I used to work with called Jon Thompson, who has died now. He was friends with Gilbert & George and with Kounellis. Kounellis really blew my mind with the installation, Untitled (12 Horses), that he did with live horses; the pieces with living animals started getting me really excited. I didn’t think it was mature, really, I just thought it had to feel important.

MG: What about the other person who was also very important for you and the other YBAs, Charles Saatchi? Could you tell me something about the relationship between you two?

DH: Well, I often say that Charles should have gotten the Turner Prize for his contributions to British art instead of me. He really changed the scale of everything. Before Saatchi, there was Cork Street in London and everything was shown there. The Waddington gallery was probably the biggest, so, you could show medium-sized paintings in there. There were no giant paintings like you got in America, for example Warhol’s Most Wanted Men. I was thinking of making small collages like those of Kurt Schwitters, which would be nice in those types of galleries, before I went to Goldsmiths. Then, when Saatchi opened his first space at Boundary Road, I remember the first time I walked in I just got snow blindness. It was a kind of shock to me. I’ve never seen a space that big be dedicated to art – even museums didn’t feel that big because of all those fire extinguishers and other stuff – this was just a white space with a gray floor with amazing art in it. After walking in there, all I ever wanted to do was to make art for that space. It changed what I was doing and it changed the scale of what I would make. I didn’t care that it wouldn’t fit in any other gallery. I just immediately started making big paintings and then never stopped – and for that reason, Charles was massive. I was one of the few artists lucky enough to show at Saatchi – it was like a dream come true.

MG: Are you still in touch with him?

DH: Yeah, I had lunch with him about four or five months ago in London. He was very depressed that I didn’t smoke anymore. When he asked me “Come on, let’s go out for a cigarette,” and I told him that I no longer smoke, he was so sad and dejected, and said, “No! Not you as well!”

MG: Is he still as feverishly involved in art as before?

DH: I think he is. He’s got huge things going on since Boundary Road, but I have no idea what the future holds. Their Rolling Stones exhibition, in 2016, was a massive hit in London. He’s not like he was to me then: he was a god-like figure in the beginning. He’s more human now.

MG: Speaking of the Turner Prize – what was more important to you: winning the Turner Prize in 1995 or having this very successful exhibition at Gagosian, in New York, in 1996 [‘No Sense of Absolute Corruption’] that exposed your work to the American public?

DH: Definitely the New York exhibition. It’s about how you measure success, the show at Gagosian was much more of a real success. I always get worried about prizes, being judged and other people making decisions about you based on who-knows-what. To be an artist you have to measure yourself on your own terms. It can get quite confusing if you start measuring yourself in other people’s terms like you do with the Turner Prize. I’m not into prizes.

MG: What about François Pinault, the other collector who has been very important in your life – how did you meet him?

DH: He met me. He just came to the studio one day, a long time ago. He’s got the biggest collection of my work in the world. He’s bought works from the beginning, he always buys; he’s incredibly supportive and he genuinely loves art. When I started collecting on a bigger scale, it was by watching François, because I thought, “Oh, I should buy a few more expensive things to get inside the minds of my collectors” – and then before I knew it I was a big collector myself.

MG: Regarding your exhibition, Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, in François Pinault’s private museums in Venice last year, did you discuss your ideas with him beforehand or did he just give you carte blanche, so to speak?

DH: That’s what’s exciting about Pinault – when he likes it, he likes it. I remember him asking me, “What are you working on next?” And when I showed him, he just got very excited and wanted to get involved. I’d already been working on Treasures for years before that. When I did my two auctions with Sotheby’s, he obviously got a bit disappointed about that because he’s Christie’s. I promised him that I would do a big thing with him after I did the auction with Sotheby’s. He was just disappointed, but then he bought from the auction anyway.

MG: Are you planning to do another auction directly with Christie’s?

DH: I think exhibiting Treasures is big enough.

MG: What about you as a collector: do you collect what you think is great art or do you buy because you want to support friends?

DH: There’re many reasons, and in a way they all come together. I would definitely support friends, but even if I support friends, I buy things that I like. When I was younger and I was making money and no one else was, there was this big divide between me and friends, which was becoming a bit of problem. When people started asking to borrow money from me I got upset about it. Then a friend just said, “Why don’t you buy one of my paintings?”, and I thought, “Yeah, why don’t I?” – and by buying my friends’ work, they could come and drink with me if I was in some expensive place! I did it for that reason, but then, in buying artworks, you really become attached to them and you want more – so the whole thing escalates. I would never buy anything I didn’t like – but there are many different reasons to like things.

MG: Do you have a big collection at the moment?

DH: Yeah, it gets bigger every five minutes.

MG: Are you buying post-war and contemporary art or are you also making excursions to other periods?

DH: I love contemporary art but I collect other things as well. I’ve got a huge skull collection. I collect Haida art, which is an indigenous tribe from the Pacific Northwest Coast, that I love. I’ve got quite a big collection of their work. My skull collection contains more than 1,000 different skulls. I collect Chinese scholar stones as well. I collect photographs of atomic bomb explosions.

MG: The idea is to display them all at your Newport Street Gallery in London?

DH: Yeah, that’s the idea.

MG: Do you also think about making exhibitions at Newport that aren’t related to your collections?

DH: Originally, the whole idea of building the Newport Gallery was to showcase my own. I’d been feeling guilty because I had so many boxes full of things that had never been seen by anyone. After doing a few shows and borrowing a few things, I realized it’s a kind of egomania to just think you can show your own collection. It’s impossible to get every single important work made by an artist you love. When you do a show, there may be two or five or ten works that you want to borrow to make the show perfect. So I’ve changed my mind a bit.

MG: Do you have a lot of your own work?

DH: I do have a lot. I kept things and I buy things back from other people sometimes – I’m a hoarder. I’ve also got a huge collection of my own clothes. I was looking in my wardrobe the other day and I thought, “I’ve got more clothes than I could possibly wear in my lifetime.” People keep talking to me about getting rid of things – I find it very difficult. I collect cars as well.

MG: How many do you have?

DH: Fifteen, but I can’t drive.

MG: So why do you collect cars?

DH: Oh, my friends drive them. They drive me around everywhere!

MG: Do you have a car for every single mood?

DH: No, I just buy them. My dad used to be a car salesman, so I was into cars, but when he wanted me to learn to drive, I rebelled and refused. So I love cars but I never learned to drive.

MG: You could still learn to drive if you wanted.

DH: I’ve got a provisional license but I also get quite a lot of ideas when I’m being driven around – looking out the window.

MG: What about your other fascination, the one with death. You once mentioned that you’ve been thinking about death every day since you were seven.

DH: I think everybody does but a lot of people try to sweep it under the carpet. I was always told to confront things that can’t be avoided – and you definitely can’t avoid death. That it’s important. I suppose in the Western world we are fucked up, because the way we deal with it seems wrong to me. Somehow art seems to be connected to death. I spoke to my friend, Ashley Bickerton, the other day, when his father had just died, and I said, “Oh, that’s terrible, that’s never good.” And he said, “But you’re never gonna die, just your body will.” I replied, “I think I’d like to turn it the other way round: I’d rather that the body lives and everything else dies.” There are no answers, only questions, and death is a big question.

MG: Death is connected to art and art is connected to religion. There are a lot of religious and ritualistic elements in your art.

DH: As an artist, I feel very connected to the past, and I think that contemporary art is connected to the past as well. I was brought up Catholic until I was twelve so I was indoctrinated as a child, and it’s quite difficult to get rid of the imagery whether you believe it or not – indoctrination works very powerfully against logic.

MG: Which is sometimes not so bad – in the case of Catholicism, you get a big part of Western art history free of charge.

DH: I love these stories. Every religion has great stories.

MG: You have always been rebellious towards the art system. Your auction at Sotheby’s, which meant a direct sale of your works through an auction and you avoiding the gallery, was quite a rare event in the Western art world – why did you do it? It wasn’t nice towards your dealers really.

DH: Oh, I don’t know – I quite like the idea that it’s not nice for the dealers. I suppose I may just enjoy risk too much. I’ve been lucky that a lot of the things I’ve done haven’t failed. When I look back, it’s really risk that is the common thread – I don’t know if that’s a good thing. A lot of people say, “It’s amazing, what you did,” but to me, it just looked risky and I feel lucky that it worked out. If the Sotheby’s auction had been a few weeks later it might have been a different story. Everything’s a celebration of art’s possibilities and of what artists can do, really. I remember thinking, around the time of the Sotheby’s auction, that even if it fails, what I was attempting to do was exciting in its own right – it’s not just about whether you succeed or fail but about what you’re trying to do. I remember thinking that artists in the future would believe it was cool even if it failed – I was hoping they would. It was about putting the power back into artists’ hands.

MG: Going back to your show in Venice, which was also quite a risky undertaking, after reading many reviews, you could say that the critical reception was negative but the collectors’ reaction was positive. What does this say about the art world, in your opinion

DH: I didn’t really read it like that. I thought the critical response was very good. There were a few reviews in the beginning that were negative but I felt that, in the end, it leveled out. What I liked in at the end were the mixed feelings, with a lot of critics disagreeing – some said, “It’s great!” while others called it a flop. The collectors seemed to buy, though obviously not everybody. It felt polarizing across-the-board. A lot of people liked it, a lot of people didn’t – critics and collectors alike – and that made me feel like I was on the right track, really. I remember, after reading the first two reviews, which were very negative, I thought, “Oh my god, I really hope this isn’t not gonna be a negative thing again,” because it’s quite hard to deal with when it’s just all negative. But then, some positive ones flowed back in and the critics started disagreeing with one another. I thought it was gonna be great.

MG: After all these years, you still haven’t gotten used to negative critics?

DH: Well, I don’t think anyone can. We’re all humans. You’ve got to try not to take things personally, but if you put your heart and soul into something and then it gets a universally critical response, you’ve got to try not to believe them. I try not to enjoy the good reviews, so I can ignore the bad ones. In the end it’s about how you measure success. My manager came to me just before Treasures opened and asked, “When will it be a success to you?”, and I said, “It already is now.” Success is simply to have actually achieved it. Living a life where everyone loves you is a lot easier. “Everybody loves me. The world is a beautiful place.” But this can’t always be the case.

MG: Sometimes I think that the real material of your work is not bronze or paint, etc. but actually the art system itself. As much as modernism has always tested the limits of a medium, I think you’ve also been testing the limits of the art system.

DH: I think the art system is designed to follow artists, not make artists follow it. Without artists it absolutely couldn’t exist, whereas without the system artists could still exist. I love art. I love the art world. As I was saying earlier, you really have to measure your own success in your own terms. It’s difficult if you make an artwork that you know is terrible and everyone’s telling you it’s great, and also if you make an artwork that you know is great and everyone’s telling you it’s terrible. I’ve experienced both, so I think you just have to believe in yourself.

MG: If we speak of the art world of today and if you compare it to that of the 1980s and ’90s – are we hijacked by moral purists? You mentioned Anthony d’Offay before, with whom Tate has recently cut all links on the basis of mere accusation only.

DH: That’s got more to do with the world than the art world, really. It’s human nature we’re talking about. I can think about my time at Anthony d’Offay’s gallery separately to thinking about Anthony d’Offay as a human being. I don’t really know the facts of what happened there, but whenever you get people with power, you’re gonna get people who are abusive with power, and it’s a subset of human nature which has been there forever, though nobody likes it. It’s is in the press a lot more now but I don’t know if that means there’s more of it or if it’s just being spoken about – whenever it’s happened, it’s never been a good thing, has it.

MG: I read in an interview that you’re now doing yoga and that you’re going to therapy, which sounds like you’re cleansing your life.

DH: I’ve got children as well.

MG: How old are they?

DH: Twenty-two, seventeen, and twelve.

MG: So they are almost adults.

DH: Yeah, almost. They live with me. I think they got me to change. I’d been partying for about twenty years and it was really great, we got drunk and did a lot of celebrating – and after a while it takes its toll. I’m fifty-two now. I remember, when I started, I could drink every night and never get a hangover. I didn’t even know what that was. Then, I stopped and a hangover would last me like seven or eight days and they were very painful. The moment I stopped was like, “Aw God, the party’s over.”

MG: It’s unbelievable that you could be so productive, having such a heavy life of partying.

DH: I suppose that’s through getting other people to make your things for you. You set things up in the studio, then leave. I remember, once I got banned from going into my own studio because I would distract everybody and make them all drink and start partying and they said, “Just stop coming in!”

MG: You then continued making most of the series you started for a long time.

DH: I remember when I was making the Natural History works, I wanted to do a zoo of dead animals, I didn’t really just want to make one formaldehyde work. I wanted to do an endless series of Spot and Spin Paintings. I was very much thinking of endless series before I even started.

MG: Which of your works was in a way the most surprising to you?

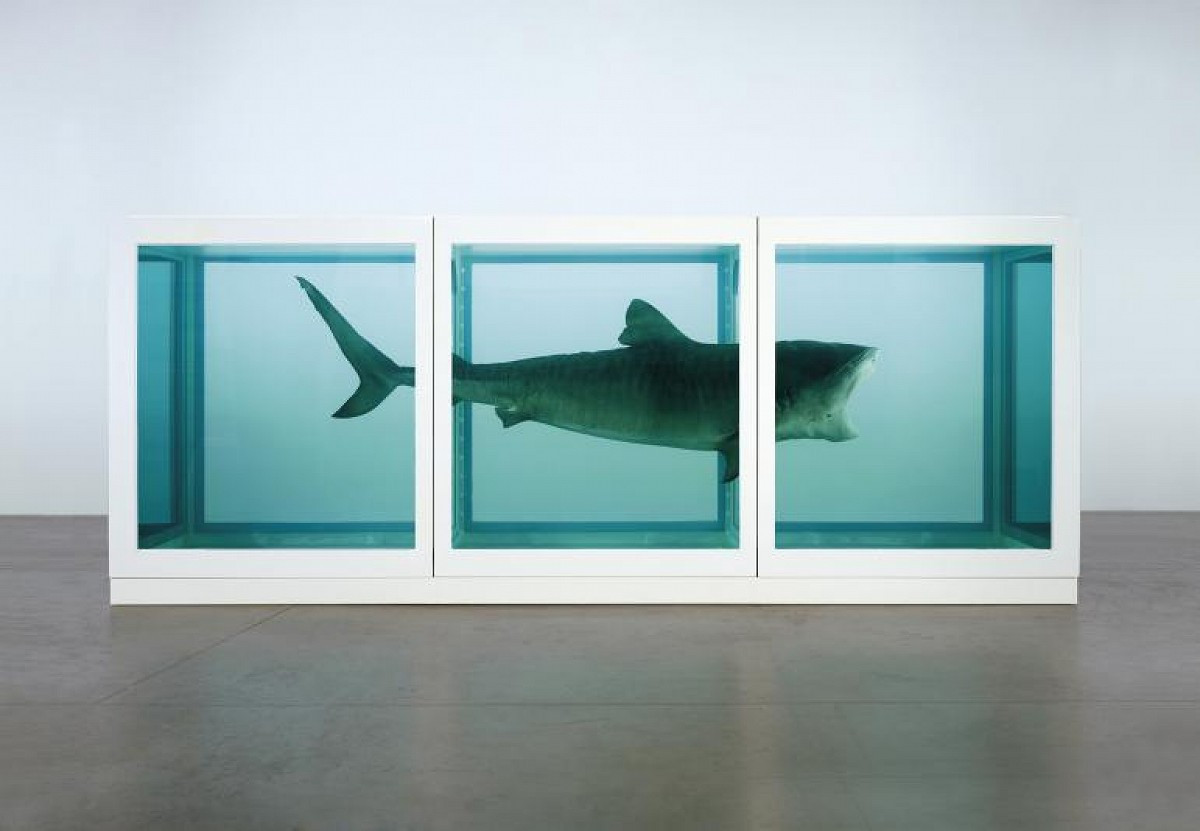

DH: I suppose the fly pieces that we talked about earlier, A Thousand Years and A Hundred Years. They were quite difficult because I made them without using the studio and they were quite complicated. It meant that I saw the work for the first time when I first exhibited them, so it’s like you have five minutes before the show, you let the flies out and it was the first time they came out. They just felt alive in a way that I couldn’t control. The moment it went from an idea to reality, I lost control. It felt really strange. My top works would be the shark [The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living], For the Love of God, A Thousand Years, The Golden Calf, and a few more.

MG: What happened to For the Love of God?

DH: It’s in a vault in London. It’s been on display in Oslo quite recently at the Astrup Fearnley Museum.

MG: In retrospect, did you correctly judge the financial risk that you’d taken?

DH: I think so. I remember being quite worried about it not turning out the way I thought it would, whether the value of the diamonds and the precious metals would always be salvageable. You always have the diamonds, so, in a way, there’s is a safety net. But I think it was a lot of money to be spending and, of course, it did get uncomfortable for a while.

MG: What about your next project?

DH: Which one? I’ve always got lots of ideas. The next thing coming up is Houghton Hall with the Colour Space paintings – the spot paintings I made recently, which were based on the very first two spot paintings I did. I’m always playing around in the studio, having crazy ideas. I feel quite good, because I’ve been working for ten years on different ideas, so let’s have it out in the world.

MG: After being a part of the art world for thirty years now, what do you think has changed?

DH: I don’t know. It seems to be more diversified and fragmented. It seems to be lots of small art worlds. In a way, it’s gotten Warholian, hasn’t it? Everyone in the future is gonna be famous for fifteen minutes. You see a lot more things occurring. Generally, the public seems to be a lot more interested in art than when I started. I think now, with Instagram and things like that, there’s so much stuff to see and do and look up. It seems to be changing, but I like the way it seems to be changing.

MG: You are also active on Instagram – do you like communicating through social media?

DH: As long as they keep it simple, I like it. It’s another way to say what you want to say. I just thought since we have this medium and I’m using it, I should make sure it’s good, it’s just about me and just about the work. I was quite surprised by how many people have said, “what you’re doing is great. I love it. Keep doing it.” My son, who’s seventeen, said, “I love your Instagram, Dad,” and he’s got a huge following on Instagram as well.

MG: You once said that good art is always very simple and should be positive – and I was wondering why art should be positive?

DH: Because the meaning of art is positive, the actual function of art is positive, the process of art is positive – it doesn’t make sense otherwise. If you are truly depressed, you are inactive and you don’t make art. I think art is, by its very nature: let’s do something, let’s create something – a very positive thing. It’s hopeful. I think about it in terms of singing songs – you can sing a depressing love song but if a friend calls you up and wants to take you out for dinner to tell you how depressed he is, you don’t really wanna go – and that’s the difference between art and life. Art by its very nature is positive.

MG: On the other hand, you also address issues of mortality and death…

DH: If you look at Picasso’s Guernica, it doesn’t make you want to give up, it makes you want to change the world. You can say that it’s about death, destruction, or abuse of power, but the truly negative impact of it is that you don’t do anything – there is no art in death.