Cory Arcangel

Published: January, 2023, Interview with Cory Arcangel for "New Waves. Contemporary Art and The Issues Shaping Its Tomorrow", Skira

December, 2019

Marta Gnyp: I’ve never played computer games and I have a very little understanding of technology. That’s the context from which I’m digesting your art. And I’m older than you.

Cory Arcangel: I’m not young myself. For example, I’m a newly mid-career artist. It is a new reality I am slowly adjusting to.

MG: It’s horrible, I went through the idea of middle age.

CA: Yeah, it’s brutal. Why are we doing this interview?

MG: I’m trying to find artists who have the potential to become important for art history.

CA: How can you know who is actually gonna be important?

MG: I can’t. I’m speculating using my subjectivity.

CA: What if I never do anything ever again? [laughs]

MG: Nobody ever would take me seriously.

CA: Lol.

MG: You’ll never know. We are now facing a re-evaluation of so many artists; hundreds of artists of color and older women artists are being now re-appreciated. The current history of the 20th century looks quite different than ten years ago. Still, we can try to find out who could make relevant work. The area of technology you are working in, it’s very important.

CA: Well, that’s the age we live in.

MG: Exactly. Let’s start chronologically, it’s probably the easiest. In 2002 you made two important works, one is I Shot Andy Warhol and the other is the Super Mario Clouds. I was wondering, whether I Shot Andy Warhol was a statement of your generation, or yourself against Pop Art, or the art history, as if you were saying that Pop Art is actually something that’s happening now on the Internet. Or was it just a coincidence that you chose Andy Warhol?

CA: It definitely wasn’t any kind of statement. I was twenty-four, I wasn’t even old enough to know how to make a statement! At the time, even the idea that I would be included in any kind of mainstream contemporary history would have been laughable, because the works like I Shot Andy Warhol at that point twenty years ago were not considered serious art; it’s important to remember that kind of context. I was just a kid, not yet interested in contemporary art and its history. I didn’t have any aspirations for those works other than to make these things that I thought were interesting. More specifically, in the game that I took apart – Hogan’s Alley – I was only able to change the graphics if I wanted to keep the game playable. And therefore, it made total sense I would do I Shot Andy Warhol – it was kind of a funny joke. Also, the third part of the game was already a part where the player was to shoot soup cans, so it was all kinda pre-ordained.

MG: At that time, you finished more or less your education at the conservatory. You were a very well-trained musician, you played guitar – I understood you practiced eight hours a day – you studied as well the technology of music. Then you started with gaming and shooting Andy Warhol. Why did you shift into fine arts?

CA: I studied classical guitar, and then I switched to electronic music composition. When I moved to New York in 2000, that was when I started learning about contemporary art. I learned about it just by going to the galleries and museums basically. One of my first jobs was in SoHo, and at the time, the New Museum, Guggenheim SoHo, Thread Waxing Space, Deitch Projects, and the Swiss Institute were all within walking distance. So, I would go to these places on my lunch breaks, and on the weekends, and after work to openings.

MG: Did you sense any connection to what you had learned in the conservatory?

CA: Well, it’s probably important to mention, even prior to going to the conservatory, I had a pretty good education in experimental media art. And, I was lucky that in my conservatory, the Oberlin Conservatory, there were some teachers who were very friendly to that kind of expression and so I was able to fool around with things that were not really even music when I was in school. For example, they had a digital video editing room – which was very early for that kinda thing. And even before that, I was lucky to go to a high school in my hometown, in Buffalo, that had a really strong experimental video class. So, by the time I went to New York, when I was in my twenties, even though I didn’t really understand contemporary art, I knew a lot about media art, experimental art, experimental video, and also Internet art –which had just kind of taken off in the mid-1990s.

MG: I saw fragments of the Super Mario Clouds, which is a very exciting work, and thought that this work is so popular because it attracts various audiences. There are people who knew Mario from the computer gaming and love it because of your funny intervention of erasing the protagonist and all actions. The other public, the art public, is engaged and amused, because you can plug in so many different art categories in this work like Computer Art, Pop Art, Appropriation Art, Conceptual Art and Video Art. From which perspective were you making this work?

CA: There was a practical side of making that work, and also a – and I’m not sure how to say this – wishful side. When I made that work, I didn’t really have an audience yet or any outlet for my work at all. I didn’t have connections in the world of galleries, etc. etc. I did though have a website and that related to the practical component of the work; I knew that I could show it through the Internet. The first way that people saw that piece was just a website – a page that explained what I had done, offered the source code and a tutorial how people could make it themselves. For maybe the first seven-eight years of that work, most people never saw the actual thing, but they saw this kind of explanation or documentation of it on the web. That’s the practical component. In terms of its content there was a wishful component. I knew it was possible to make digital art that was accessible, fun and also super interesting under the hood. When I had started to figure it out – around the time of making Super Mario Clouds – I was trying to do things that were both technically interesting, but also just accessible and also spoke more towards art history. Does that make sense?

MG: Absolutely.

CA: That was the kind of bridge I was trying to cross during those years. I was just trying to figure out how to make digital art that could co-exist along with just stuff I was seeing in the galleries at the time.

MG: Was giving instructions how to make this work an important conceptual part of it?

CA: I would say probably yes, but it was more simple than that. It was just how the piece made sense to be presented online. This was before YouTube, so it just seemed to me that the way the piece could exist online would be in these instructions. Online the piece was a different kind of gesture. If you look at my website, it has a link somewhere to the original Super Mario Clouds page. And later on, I got the opportunity to show these pieces in galleries and institutions.

MG: Exactly, in 2003 you started working with Team Gallery and then you became actually properly represented in the art world or would you call it an art industry?

CA: Art industry.

MG: Why do you always say art industry and not art world?

CA: [laughter] I think the art world just sounds so friendly; I feel like “industry” is a little bit more of what it is. It’s not a friendly place.

MG: You’re right, it is industry. But if you use the term “art industry” there’s always this connotation with Adorno which makes it kind of very critical of the consumption society.

CA: I don’t know that reference.

MG: Let’s then go back to 2003 when you became part of the art industry and your Mario and Warhol became hits.

CA: [laughter] I think both of those works were successful; I wouldn’t say they were big hits, but they ended up doing what they wanted to do.

MG: For you as a young artist it meant that you had a very good introduction to the art industry having a good gallery and a work that is liked and considered smart.

CA: It was probably helpful, but at the same time I did a lot of work it the underground film world, especially at the New York Underground Film Festival. I was also doing a lot of work online. I was working in all these parallel universes. Sometimes I still do that. I came to New York and I was lucky that I was educated. I knew what I was doing in terms of making experimental video work. And I just discovered that there were all these outlets for it, and I became enthusiastic, and engaged in all these different venues.

MG: What about these underground films that you are making, or you used to make. What kind of work is it?

CA: Well, I participated in the New York Underground Film Festival several years in a row. The first year I showed a modified Nintendo game in the lobby, which is of course similar to what we were just talking about. I think the second year, I did a two-person show with Seth Price in the basement of the Anthology Film Archives. For that exhibition, I showed an archival preservation of early Commode 64 computer graffiti called Low Level All Stars. That was a collaboration with a group called the Radical Software Group or RSG. I think the third year I did a performance titled Sam Simon where we projected a Simon & Garfunkel concert and I covered Paul Simon every time he showed up on screen by holding a giant cardboard hand on a pole in-between the projector and the screen, so it was a kind of humorous live performance.

MG: What about your projects online?

CA: From that time, I had a project called Data Diaries. I was doing a lot of different things, basically.

MG: Was the art context so exciting?

CA: Yes. My first solo show was in 2005. It was terrifying because I never learned the practical things that you would learn in art school, like “How many works do you show?” or “Do they need to be related?” or “Do they need to be new?” I literally had no idea what an art show was! In the next few years, as I started to do more and more traditional art shows, I learned on the job what an art show was, what a gallery was, what an institution was, and how to deal with all those spaces. I learned a lot very quickly, but it was also very stressful. And as I learned more and more about contemporary art, my work changed.

MG: What new works did you want to make?

CA: Put simply, when I finally learned enough about painting and sculpture to kinda understand what I was seeing when I went to galleries, I wanted to try myself. So, around 2006 or 2007 I started very gingerly making works that hung on a wall and stood on their own.

MG: Did you consider yourself at the time a proper artist?

CA: No. That came a bit later. Once I realized there was no turning back.

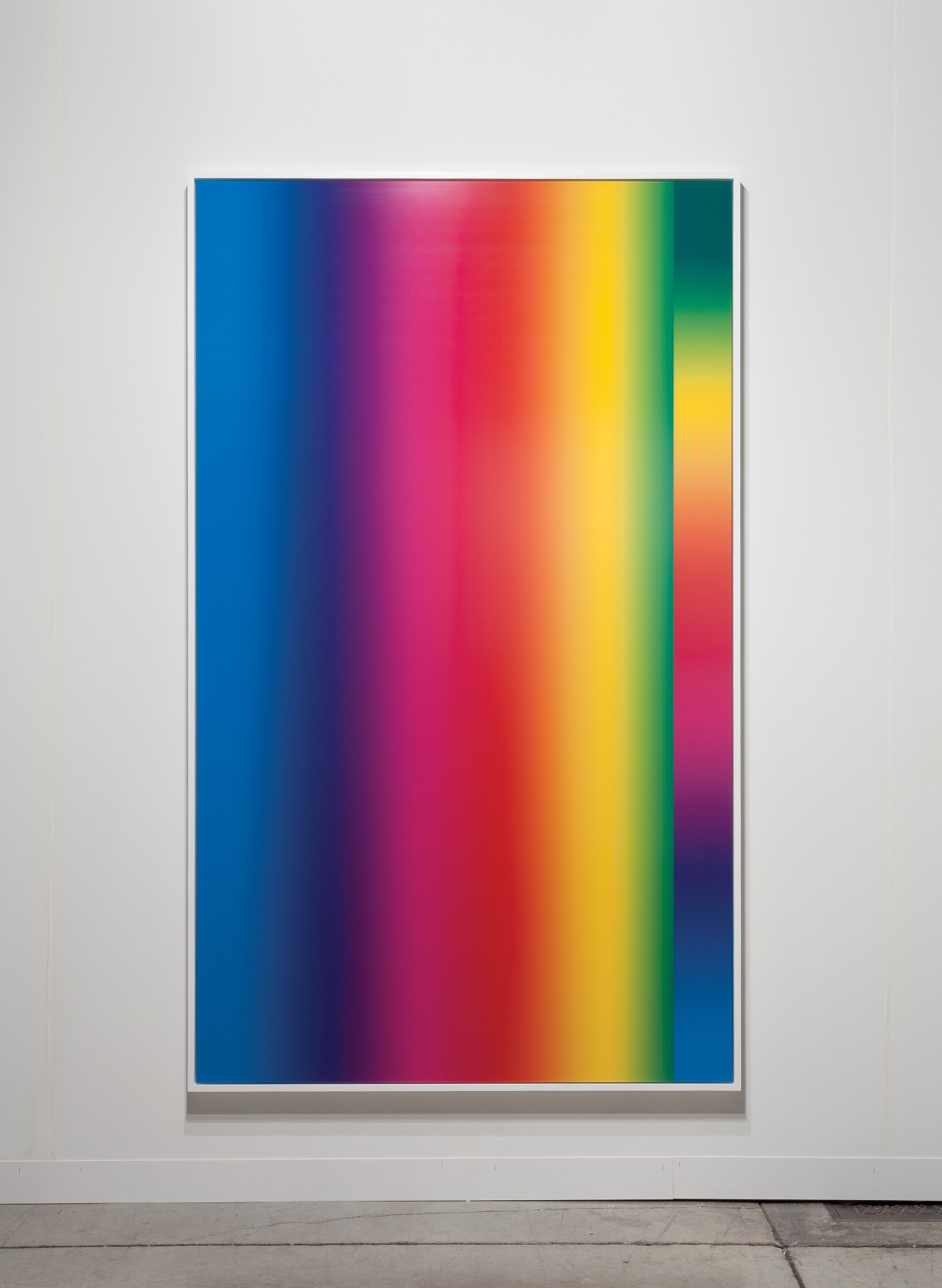

MG: Was that the context of your other work you are known for, the Photoshop Gradient Demonstrations?

CA: Yes. The first time I showed work from that series, was in 2007 in Stockholm. I found out that I could open up the program Photoshop and just use built-in tools to make some kind of color patterns. I liked that they were almost ready-made and also that they were kind of stupid and a little bit insulting.

MG: Insulting because you need five seconds to make them?

CA: Kind of; it takes five seconds to make them but much longer to print them and to make sure that there’s no dust in them . . . it’s a little bit more complicated.

MG: But you have presented them as light and easy, a kind of antithesis to a creative act that requires a lot of suffering.

CA: Yes, it’s how I would like to present them.

MG: I heard about the genesis of the work that you had a discussion with your friend Ryan McGinley. Is it true?

CA: It is true. Well, maybe not a discussion, but I saw one of Ryan’s shows at Team Gallery. And I thought it would be fun to do basically the same show – produce the photographs in the same way – but just take out his images and put in my gradients. I never had the nerve to do a whole show, which was stupid of me, but I showed one like the above idea in 2008 at Team Gallery. I upped the scale and then all of the sudden the series had a little bit of legs.

MG: And is it an ongoing series? Are you still making them?

CA: I haven’t made one in a year or two. I don’t like to say never again but, at the moment, they’re not on the front of my desk.

MG: Are they all unique?

CA: Yes. I wanted people to think of them like paintings, so I adopted the market model of paintings. Not only that, if you saw two of them made a few years apart, there would be some kind of process of discovery that had happened between the two. So, like a painter, my practice would change very slowly over time.

MG: Did you compare these works to the works of Wolfgang Tillmans? The Swimmers, for example.

CA: I don’t know those.

MG: Photography being or using abstraction and functioning as a painting.

CA: I didn’t think in specific of Wolfgang Tillmans, but I knew that they were photographs that acted like paintings. I wanted to make paintings, and still do!, but I haven’t been able to do it. I think the hardest thing that an artist could be is to be a painter. I have a lot of respect for painters.

MG: You yourself declared painting dead.

CA: Did I?

MG: You did! I don’t remember in which interview you said that painting doesn’t really have a function because it’s such an outmoded medium.

CA: My 41-year-old self would disagree with whatever self you got that quote from.

MG: [laughter] I’m happy you changed your mind.

CA: I’m surrounded by paint right now. I’m sitting in my office in Stavanger and there is paint on the walls, there is paint on this table; the computer that I’m looking at has this some kind of industrial painting covering it. We can’t discard painting because we’re surrounded by paint every day. That would be my first broad take. My second take is: art is what people think is art and you can’t ignore that there’s hundreds of years of painting. That is art, so that would be my argument against myself. [laughter]

MG: You won. You have often stressed that you work with technology and that technology becomes permanently outmoded. What do you think will happen to these gradient paintings? Do you think there is a chance that they will disappear in the long term or is this also some interesting element to it?

CA: Definitely; they could fade or whatever would happen to a photograph could happen to them. I think that’s super interesting.

MG: So, there’s a kind of incorporated risk for people who are interested in this works that they can fade or at least partially?

CA: As a photograph fades, these fade as well. There is no stable object in the world. It doesn’t exist.

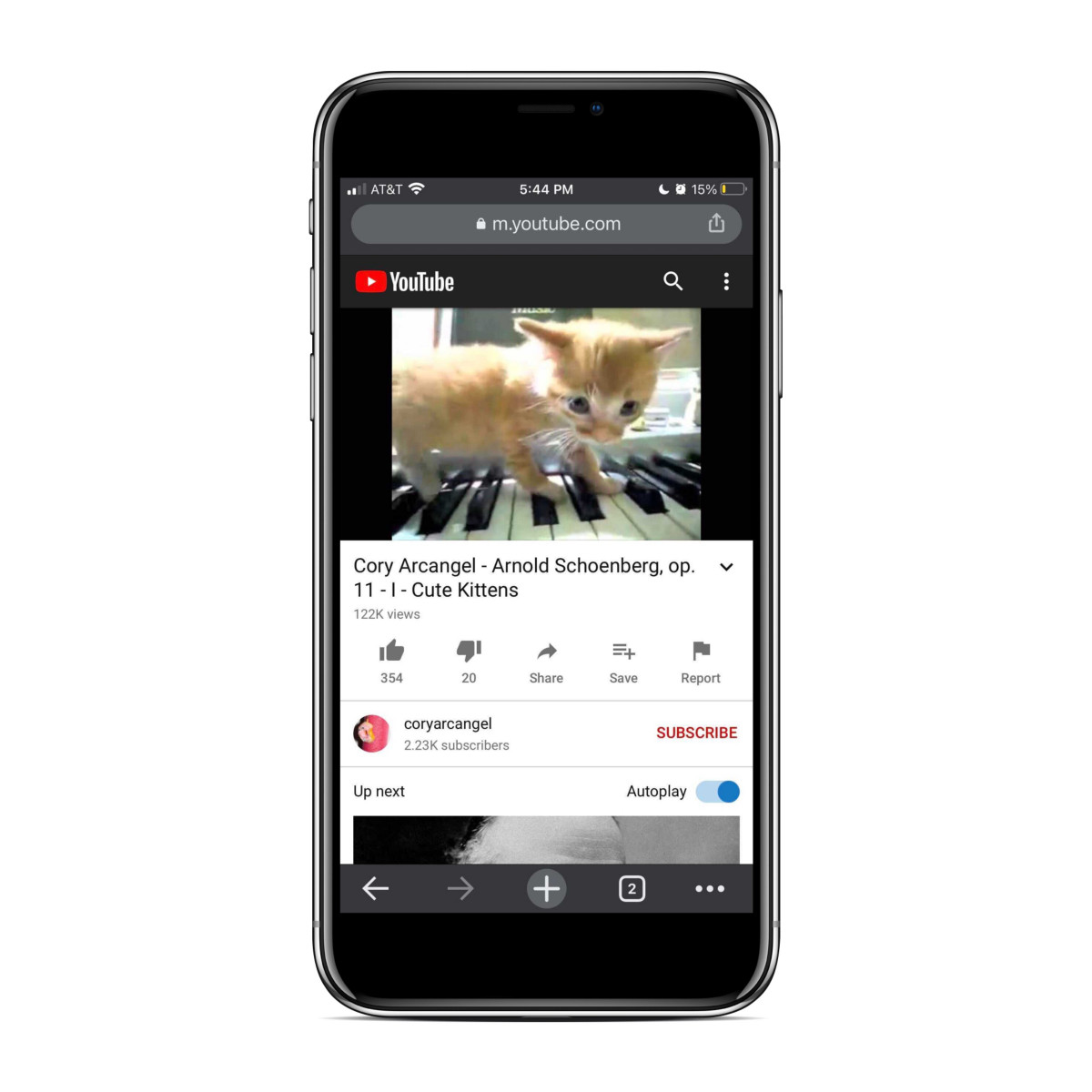

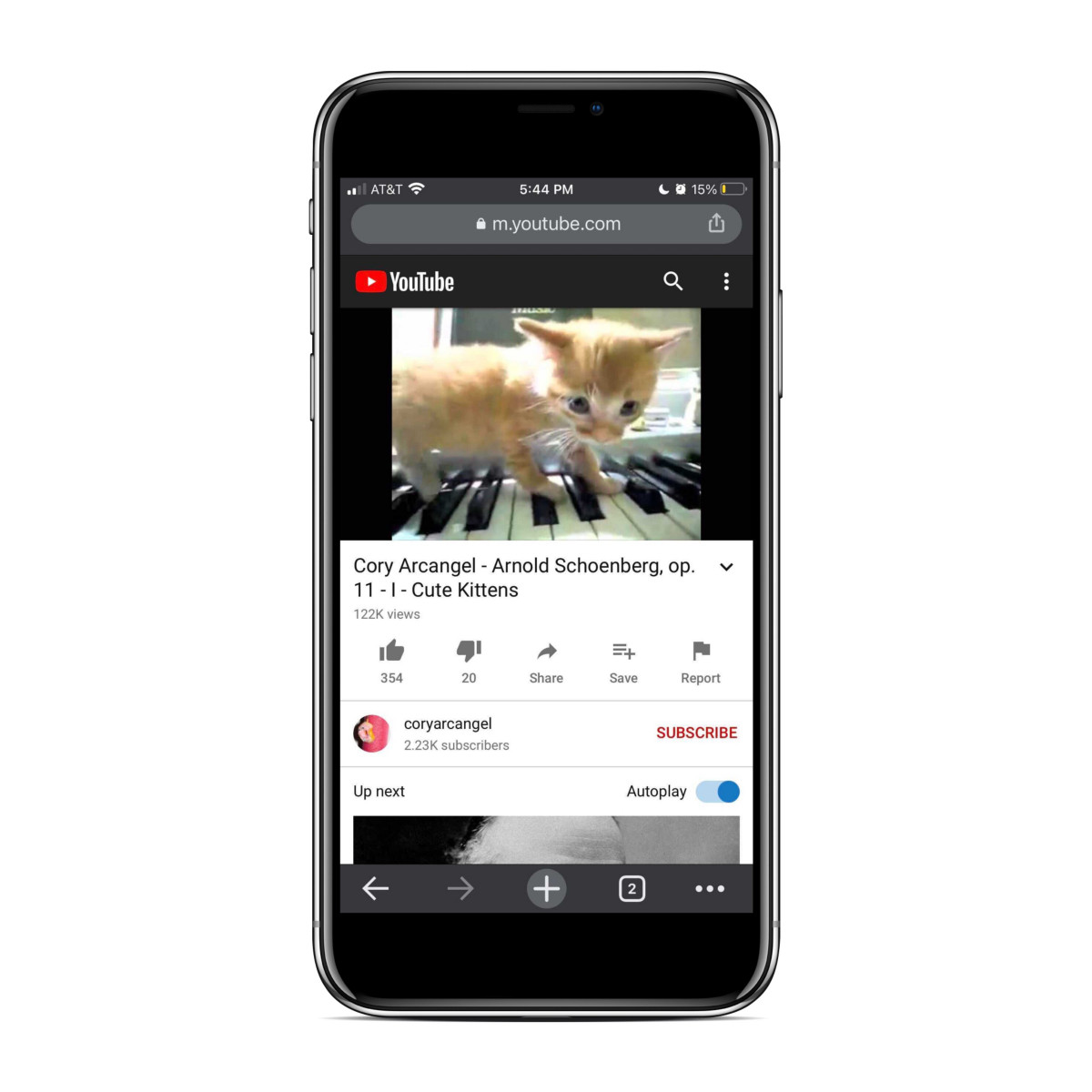

MG: What about the other hilarious, beautiful piece Drei Klavierstücke with the cats that you made in 2009? It’s so difficult to make interesting artworks with humor. Only very few artists can do that, and I found this work really outstanding.

CA: Thank you. You have to remember that YouTube showed up in 2005, so it hasn’t even been around for fifteen years. At that time, I was still figuring out the different contexts that I was trying to work in. One was online and the other was IRL – institutions and galleries. I wanted to make a piece that I thought could fit in both at the same time and do different things in each space. This piece was perfect because online it worked as a funny cat video, and people love to see animals on little screens. At the same time, I liked the idea of taking really low-res cat videos and showing them as art in an art institution.

MG: Did the two-channel presentation work out?

CA: The video debuted in both spaces at the same time: it was shown in Kunsthalle Graz in a show curated by Rock-Paper-Scissors: Pop Music curated by Diedrich Diederichsen, and simultaneously I uploaded it to Buzzfeed. Now Buzzfeed is a kind of global organization which does news and kind of funny and interesting things on the Internet, back then it was still a start-up that I was working at part time.

MG: That’s probably the secret of good art that it can function in different contexts and taking on different identities. It can be seen and understood by people who have no idea about art and also people who are experts. You can also give different meanings to it as a work of art.

CA: Yes! Some art can be that way. I particularly like art that is really super accessible. It can make sense up and down the ladder of experience of the art, of knowledge or anything.

MG: You have used music quite often in your work.

CA: I’m a trained musician and it’s still the thing that I still feel the most comfortable with. It is still very important to me; music of course is just something different.

MG Let me quote you again.

CA: Oh my god! [chuckles].

MG: [chuckles] You said that you don’t like the idea of expression.

CA: Oh, where am I saying this stuff? My god!

MG: I’m sorry, I went through your interviews.

CA: For most of my public art life, I treated interviews as if I was a musician. In general, musicians never decline an interview; if you’re playing in some town and some radio station wants you to come on, you go and if there’s some magazine who wants to talk to you, you go. That’s why I have so many interviews because I just spoke to anyone! Now that I am a father it’s a bit different – I just don’t have much time anymore.

MG: And you have always agreed with the interviewer?

CA: Yeah, probably. Who knows? Lol. So, I was against expression at some time.

MG: You said that you don’t want to make any decisions and the death of the composer is a brilliant idea, which sounds like a very post-modern attitude towards art.

CA: Oh, I know this interview.

MG: Do you agree with yourself today?

CA: Well, I was referencing Tony Conrad in that interview and his purest contribution to the world of composition. Cage still determined things, but Tony and his generation, they were trying – or at least this is my understanding – to get beyond that idea and that composition should be totally in the moment and provisory. For Western composition that was a huge contribution.

MG: Understood. I thought that the idea that you don’t want to make decisions yourself and that the structure speaks through you doesn’t apply really to your art.

CA: Yeah, probably not. Probably more so lately it’s not true. [both laugh] Maybe it started a couple years ago, when I tried to embrace a more classical concept of what an artist was. If you look at these scanner paintings that I’ve been doing more recently, there are at least references to kind of free expression, as it would be in painting. I don’t know, not sure if I agree with myself either. [both chuckle] I am changing!, and always a little bit over my head.

MG: Be glad that you are curious; you could decide as well that you have a lot of experience, knowledge and expertise in music and technology and stay with them.

CA: I could have. In 1996 art schools were not interested in people who were doing things on computers, so there was no possibility for that to happen and so if I would have been ten years younger, I would have just gone to art school. It’s just a matter of timing and my interests.

MG: Was it very difficult to learn the computer skills? You often said, that you use actually hacking as a method. Does a good hacker need to be very skilled?

CA: No, I would also disagree with that. Hacking is a term that has many different meanings, and the meaning that I would refer to in my own work is like “hacking around.” Or “hacks together something”, or to do something quick and clever on a computer, not necessarily complicated. It wasn’t that hard for me to learn the computers because I was interested in it. Now at this point I’m forty-one, and every fifteen-yearold probably has a better computer knowledge than me. You explained earlier that you don’t know anything about computers, but you have a cell phone which is a little super computer in your pocket. You know a lot more about computers than you think.

MG: You are trying to be nice. If we speak about technology and work, what about The Lakes?

CA: The Lakes series, that started in 2013, that was based around an image effect written in the Java programming language in which an image is mirrored and ripples. It was a very popular effect on the Internet in the 1990s and you would see it all over the place, and you know of course it has disappeared as these things do. So, around the time this effect disappeared, I decided to do a series about it.

MG: What did you want to achieve?

CA: I wanted to take contemporary imagery and apply this image effect, which was popular ten of fifteen years earlier. So, I wanted to produce some kind of uncanny version of the present, or maybe even an impossible past. The series is presented on commercial flat screens turned on their side. Again, I showed them in galleries like paintings, which means a flat square that hangs on the wall and people don’t need to look at it for more than two seconds. Of course, you can look at a painting for more than two seconds but it’s not a movie where you have to sit down, and it goes on for an hour or two. I’ve done a couple shows that were basically painting shows.

MG: How did you choose the images? I saw for example one with Paris Hilton.

CA: They had to feel for me kind of contemporary-ish and formally, they had to look really great mirrored and had to be in a certain resolution. So, it was a kind of technical and formal game that I played when I made those.

MG: How do you work with the series? Do you finish them for good or do you always keep the possibility open to come back to it?

CA: Usually series go on until they run out of steam. I’m just like “I don’t really wanna make it, I just can’t, I don’t know if I can make another one.” Sometimes I stop when an assistant in my studio leaves. I just don’t feel like teaching a new person how to do it. [both laugh] It can be one or the other, I don’t ever say never but at the moment, no, I’m not working on those either.

MG: What about the pool noodle sculptures – Screen-agers, Tall Boys, and Whales?

CA: I had arrived at a dead point, and I really just wanted to make sculptures. The pool noodle stuff was my first true blue sculptural series or at least to my memory.

MG: Why did it feel like a dead point?

CA: I had a big show at Whitney in 2011. After that show I took a couple years off just to reset myself. But, it’s important to note, to produce my Whitney show, I got a studio and finally stopped working out of my apartment. So, anyway, I have a studio, and all of a sudden a lot of free time, and at a certain moment I started to mess around with these pool noodles that you can get everywhere in the summer. I started to dress them up in contemporary textiles like socks, sweatpants, and electronics headphones and ipods. I had a kinda of s tudio practice. I made those for a couple years up until maybe 2014 or 2015? I can’t remember.

MG: What do you mean by resetting yourself?

CA: In the run-up to my show at the Whitney I had a show every three months for like a year and a half – that’s a lot! I did a show at Ropac in Paris and then one in Berlin, at the Barbican and the Whitney, and I think I did a show at Lisson after that. It was exhausting, I just needed a break and so I took two years off. Well, I did some survey shows but I didn’t do any shows of new work. Periodically I do that every couple years.

MG: You were very seriously ill, weren’t you?

CA: Yeah, a couple of times. In 2006 and 2009.

MG: I heard that you lost your short-term memory for a period of time, which sounds really frightening.

CA: I had thyroid cancer and the thyroid – among other things – effects memory. During treatment, I lost my short-term memory, which was really a wild experience!

MG: It must be very strange to work when a part of your memories doesn’t exist or doesn’t work.

CA: It was strange, what can I say?, it was a challenge. The world changed a little bit but actually surprisingly not that much. Eventually the memory came back when my treatment ended, but I did learn and retain a lot of things from that experience. Like writing everything down, which helped me to become really organized. It also helped me understand that my life needed a structure. When you’re having trouble remembering things you can’t improvise so well. I’m like really interested in to-do lists, spreadsheets, databases, and things like this – just writing everything down, and not relying on memory for anything important. Before my sickness, I was a un-organized mess.

MG: With the busy schedule you have, why did you want to set up a fashion label?

CA: [chuckles] That’s a good question! Well I was approached by Universal Music with an offer I couldn’t refuse. They had a subsidiary or corporate division that handled their merchandise and they asked me, “Would you be interested doing a merchandise deal with us?” At that point they had only represented musicians and so I guess I just thought, “How can I say no to this?” [laughter] If they are doing a merchandise with Justin Bieber and Lil’ Wayne and Metallica, I just was too curious to understand what it’s like to have a line of merchandise.

MG: That’s how Arcangel Surfware started.

CA: Yes. My kinda thinking was, if one of the ways that musicians exist in the world today is by having their own clothing line, I also want to have my own clothing line. I want to see what that means.

MG: And what is it like? What does it add to you, to your artistic career or to your understanding of art, your understanding of popular culture?

CA: Practically, it was a totally new experience. It’s a totally different industry. So, in the beginning it was a lot like my experience with contemporary art. I didn’t even understand the terminology they were telling me about – deliverables, assets, and things like this. And working with the creative team there was fascinating. You have to learn how to navigate that system; going to meetings in the Universal Building in New York was very fun and cool. I eventually left that contract about a year ago, but for the first four years Arcangel Surfware ran under Universal. I still have the clothing line, and I ended up opening a store here in Stavanger. I have to do things to understand them.

MG: I fully understand that.

CA: I also remember when I first moved to New York, Keith Haring’s Pop Shop was still open and I always thought these kinds of gestures were very interesting.

MG: Do you have a big studio with assistants working for you?

CA: I have a studio in New York still. There are three part-time people who work there.

MG: But you live in Norway, so you are kind of remotely controlling your studio?

CA: Yes, I work remotely. Speaking to what we were just talking about, it is a situation where it helps to be organized, and also into production spreadsheets, and things like this.

MG: What does technology do to us, how do we change with the technology are very important subjects in art throughout the 20th and 21st century. Again, you made two statements which I think are both very interesting. You said in 2009 that Internet is full of half-truths, which turned out to be very true especially in the context of alternative facts.

CA: That’s true.

MG: That was a kind of very wise and very profound analysis of Internet. And the second one – you said that everything is going to be specialized in the future, we are not going to have universal global stars like Michael Jackson which I think . . .

CA: That’s wrong.

MG: We have Beyoncé, Kardashian, we’ve never been so in love with global celebrities.

CA: We found out that Internet even makes bigger stars!

MG: What do you think about technology now? What does it do to us?

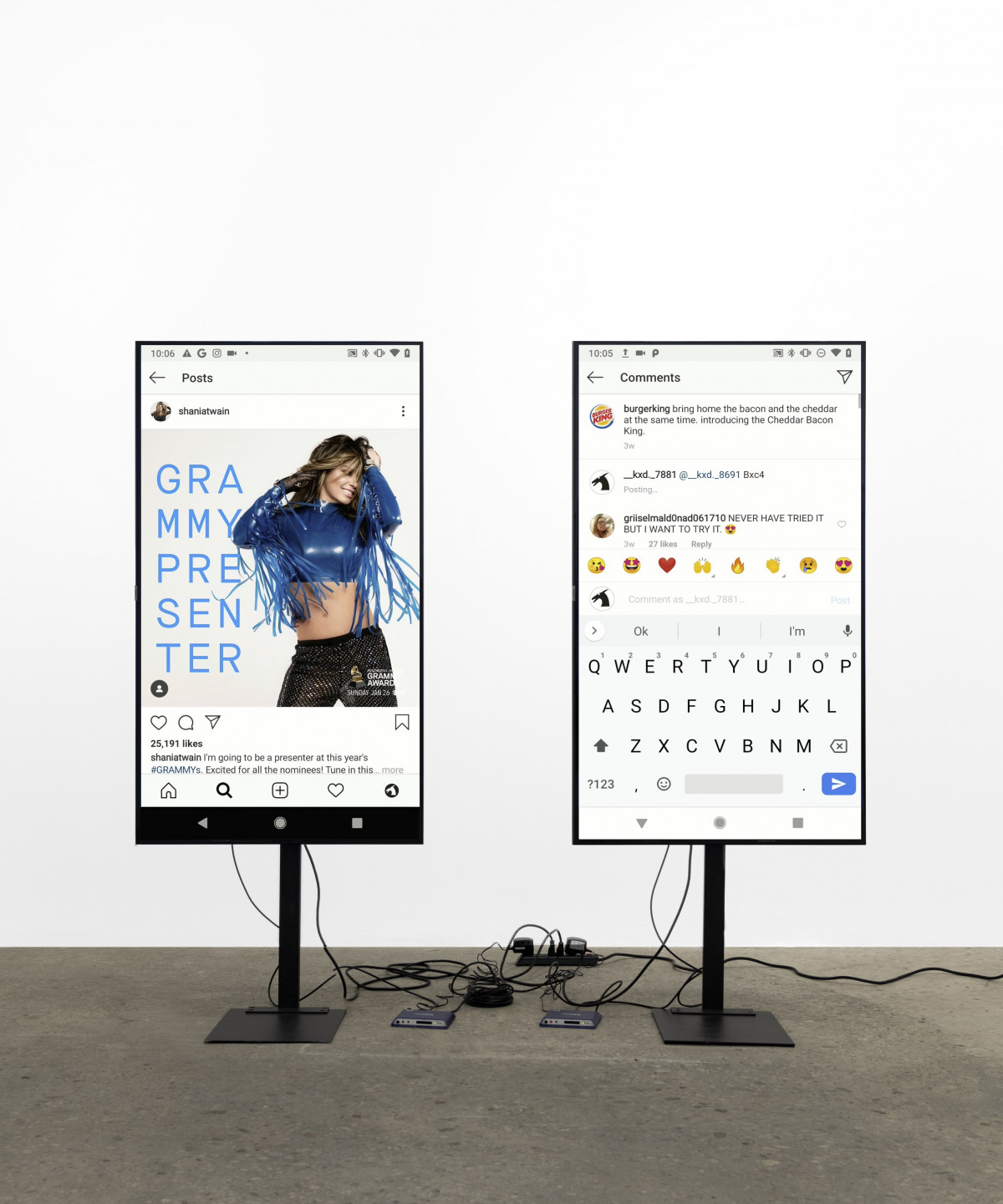

CA: I think it’s super violent. People often say the word “technology", they just assume the digital aspect of it.

MG: You are right, I mean the digital technology.

CA: I think it’s really unbelievably violent. There’s so much stuff that I couldn’t have ever predicted. Stavanger, where I live, is a very very quiet town. And, I had to take social networks off my phone because I just found that I couldn’t deal with going back and forth between the world of online social networks, and then the real world of the quiet town that I was living in. It’s such a violent transition that I was having trouble of doing it, you know? Like dipping my head in cold water. When I lived in New York I never noticed this difference. Maybe it’s just because I’m older or where I live . . . I just feel how much violence is in these systems like Instagram. People are figuring this stuff out, like Facebook recently had – there was the mass shooting in New Zealand which was livestreamed on Facebook. People are realizing these systems really are a little out of control.

MG: Exactly.

CA: It’s so different than it was ten years ago! It’s almost unrecognizable to me.

MG: Are you going to do something with the subject of this uncontrollable violence and of the digital technology?

CA: Well, that’s hard to say. The work comes when the work wants to come and I’m not entirely in control of it, it’s more like I catch it or I harness it. With that said, I do like some work to be of its time. I like it when you see an artist’s work and you think, “Oh, that really had to be made this year.” It doesn’t necessarily mean it’s topical, but I like if the work is just super contemporary.

MG: The last subject, what about the Andy Warhol preservation project? What did you learn from going through Warhol Amiga collection and his archives?

CA: Oh, I learned so much! In the near term, I learned a lot about Andy Warhol’s digital life. I learned about how many Amigas he had and when he might have used the Amiga, whom might have used the Amiga with, why he had the Amiga. I learned about collaborating with the Carnegie Computer Club, this great, and incredible volunteer computer preservation club at the Carnegie Mellon University. I learned about what it was like to work with them – some of the best engineers in the world – who were doing this kind of stuff for fun and had a really good attitude. I learned what it was like to work with a museum that housed an estate collection, the Andy Warhol Museum. That was another really incredible learning process about how estates work and how archives of that magnitude can function. They are still digging through Warhol’s stuff. It was an incredible way to get close to his work.

MG: After you had shot him fifteen years ago?

CA: [laughter] I think maybe all the New York artists of my generation are interested in him. Well, I can’t speak for all of them, that’s ridiculous, but many. Perhaps it’ll change. I learned how to actually bring my tendency to be interested in issues of preservation and obsolescence outside of my own work, which I thought was a big step and one that I was really happy that I was able to take. So instead of making work, I just helped preserve and discover another artist’s work. That was a really important thing for me because it’s something I will continue to do. A couple years later I worked with Tony Conrad and I published his 200-hour long piano piece. I’ve expanded my practice beyond my own work.

MG: I can’t wait to see your next project. Thanks a lot for your time.

CA: Thank you for your time. I appreciate your intense research, finding out things that I no longer even believe. [both laugh] It was a lot of fun.