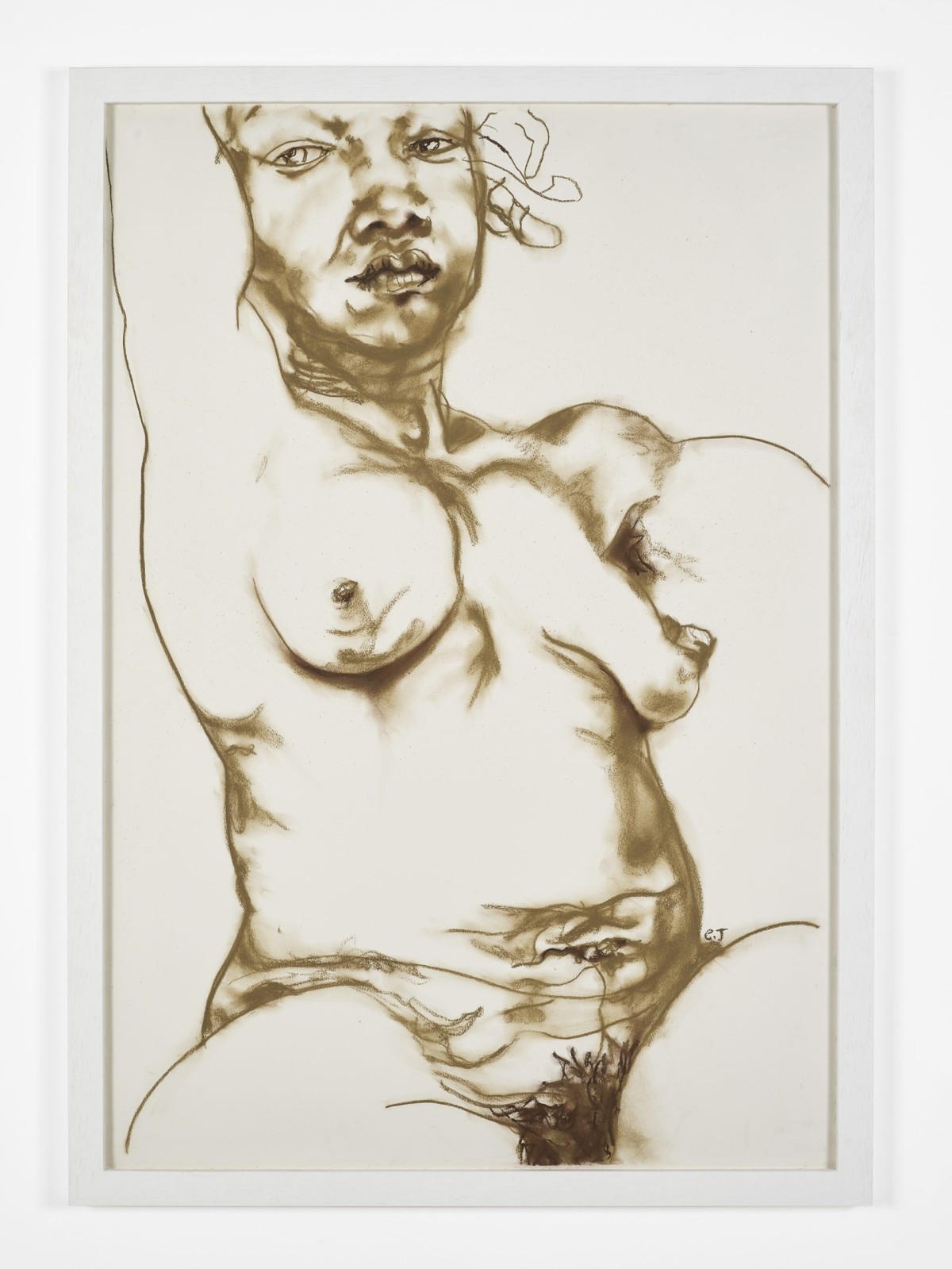

Claudette Johnson

Published: December, 2022, Interview for the book "New Waves. Contemporary Art and The Issues Shaping Its Tomorrow", Skira 2021

Marta Gnyp: Let’s start with the unavoidable question in this period. How did you spend the corona lockdown time?

Claudette Johnson: Well, initially I had to self-isolate, but for the last five or six weeks I have been able to come to the studio quite a lot. My studio is within walking distance of my house; it’s very quiet here, so I have been able to just carry on, though not quite as normal, in recent weeks. Perhaps it’s made me turn in on myself even more than usual as I haven’t been able to have models. Instead I have extended the small warm-up self-studies that I normally do, into a series of larger drawings.

MG: You probably work alone.

CJ: Yes. I have a self-contained studio within a larger studio that I share with one other.

MG: The lockdown in UK softened only recently. I think on the continent we were a few weeks earlier than you.

CJ: That’s right. Pubs and restaurants will be opening tomorrow but that won’t change my current routine.

MG: What about the other big issue that we have been facing the last weeks, the protests related to Black Lives Matter. How did you experience that?

CJ: I see the BLM as the necessary response to the entrenched racism that we are still struggling with in society. George Floyd’s death shocked me to my core. I am still reeling. I didn’t like the way that it was reported on television channels here. His final moments were shown repeatedly without any warning as if it were commonplace and as if it was not deeply distressing. As if it didn’t really matter. It illustrated perfectly why this movement is needed. To me it seems that many people are numbed to black people dying in all kinds of settings. The manner of his death has been rightly compared to a modern-day lynching.

MG: Do you think that there is a big difference between the US and Europe in this sense?

CJ: I haven’t ever lived in or even visited the States, so my views come from what I witness from a distance. Although black people have been part of British society since the 16th century, we have only become a significant minority relatively recently in the second half of the 20th century. British people on the whole were quite dislocated from their colonies and the brutality of slavery whereas African Americans were part of the American story from its inception. The racism that exists in both societies today stems from the stories that were told to justify slavery. In that way, I think the similarities between the experiences of Black Britons and African Americans, are greater than the differences. I was a teenager during the American Civil Rights protests but vividly remember the power of the slogans that crossed the Atlantic – Black is Beautiful, Black Power, Power to the People. I really believed things were going to change. However, there is still collective amnesia about Britain’s colonial past as evidenced by the failure to understand the anger that led to the pulling down of Edward Colston’s statue.

MG: We’re arriving at one of the core subjects of your work being identity and subjectivity of black people, especially black women. If I understand it correctly, the 1980s were the forming period that created the ideas and concept of your work.

CJ: Yes.

MG: During your studies at Wolverhampton University?

CJ: At the time it was polytechnic, but it became a university probably a year before I completed my degree.

MG: I read that you were the only black person in your class.

CJ: Yes, on the Fine Art course in each year group, there seemed to be just one black student per year.

MG: How was your study?

CJ: Looking back, I think I already knew that I wanted to focus on black people in my work early in my first year at Wolverhampton Polytechnic, but a number of influences from black friends to James Baldwin and Toni Morrison, to Roots Rock Reggae music pushed me to formulate a black aesthetic that I felt was both feminist and rooted in black experience. Being one of so few black students studying fine art, I was a microcosm within a microcosm. The work I made created a mini society of black people that welcomed me to my studio each morning. At that time, there was no mention of the black artists that I now know had preceded me, so I believed I was working in a vacuum devoid of black British artists, or art that featured black people as primary subjects. We seemed to be on the edges of society, on the edges of history, footnotes to someone else’s story. When I started making large-scale works, I knew that the black figures had to be central and bold, but at times fractured, truncated to reflect our invisibility in British society; the absences in the stories that we had been told about ourselves. I countered the isolation by attending the student Afro-Caribbean Society meetings.

MG: What was the goal of the African-Caribbean Society?

CJ: The African-Caribbean Society was there to connect black students with each other. I remember meeting a number of South African students who gave me an insight into life under Apartheid. There were talks and socials. The polytechnic was divided into six floors. Fine Art was on the top floor and the other art departments below. There were more black students in other departments, especially in Graphic Design and Textile Design. The Society introduced me to a much broader range of black students than I would have met otherwise.

MG: You are British. It is interesting to see that you explored different routes to seek your own identity.

CJ: At that time there was no easy compatability between being black and being British. A black person was always assumed to be from somewhere else. I can’t count the number of times I was asked where I was from and met with disbelief when I said Manchester! The idea of Britain of multi-racial Britain did not yet exist. I was part of the first generation of black people born in Britain after the migration of West Indians who were invited here to work in Britain’s core industries, so, to some extent our generation had to invent ourselves. However, a black British identity came more easily than an English one. English was what our parents called native white people. It wasn’t what we called ourselves.

MG: Later on, in 1982 you joined the Young Black Artists organization.

CJ: What became the Black Arts Group was originally Wolverhampton Young Black Artists. Eddie Chambers and Keith Piper were from Wolverhampton, Marlene Smith was from Birmingham and I came from Manchester. We were all studying art at different universities in the Midlands but we would hold meetings in Wolverhampton.

MG: Your goal was to become more politically active in the territory of arts? Did you want to achieve something for black culture?

CJ: I thought that art could foster change. Black women seemed to be completely absent from Western art narratives and invisible in the media except when presented in stereotypical ways. I wanted to interrupt that. I wanted us to be seen. Visible as women with agency and power, as I knew the women in my life to be.

MG: You left the movement very quickly only one year after, in 1983.

CJ: It had been a very intense period and shortly after the Black Artists Convention we found we had irreconcilable differences. Nevertheless, I continued to show with various members of the group for some years afterwards and although it might look as if there was huge conflict in fact, my overriding memory is of the support and encouragement that we gave to each other. After the convention there really seemed to be a growing network of young black artists reaching out to each other from all parts of the country.

MG: It seems a very complex and complicated subject because there are so many different intersectional ideas representing various interests and groups in it. You were always interested in the position of women.

CJ: Yes.

MG: Let’s go to this famous congress in 1982 in Wolverhampton where you were talking about the specific subject of black women subjectivity also in relationship to sexuality, that was interrupted, questioned and led to a spectacular breach in the group, if I understood it correctly. Was this really such a problematic subject?

CJ: Looking back and having listened to the recording I know that I was heckled during my talk. I think what some of the attendees couldn’t accept my exclusive focus on black women. Or more precisely they couldn’t accept the way that I represented black women in the work. The work I showed presented women who were sometimes naked, abstracted posturing, pushing out from the boundaries of the work. I imagine the absence of men in the work was very telling. As I’ve said before, by the end of my study at the university, I was focused exclusively on black female imagery.

MG: Did you know at that time how problematic that issue was? Did you consciously want to provoke, or were you surprised with this emotional reaction of people towards the speech?

CJ: What I remember, and I have to tell you that there’s a lot that I’ve forgotten – is that I was surprised by a comment that was made by one male attending at the conference who interrupted me to say, “Well, your work, I can’t see the difference between what you’re doing and what any of these white male artists were doing, you’re doing the same thing.” It surprised me that he didn’t think that the way I’m presenting black women was sending a different message and telling a different story, than say Manet in the way he presented women in his work, for example. That surprised me.

MG: Did this comment make you change your way of, let’s say, representing women? Did you try to make your message clearer or you just thought that he didn’t understand that?

CJ: No, his comment didn’t make me change my way of working, I thought he didn’t understand. But he probably just didn’t like my work! In the work, I was trying to address black women’s invisibility and I was doing that with figures that were to some extent provocative. They were dark and troubling works, some of them, women with clawed hands, arching backs, broad thighs, flexing, crouching, taking space. They were fighting for their lives and it wasn’t pretty. I think the style and the content were antithetical to the thinking of some of those present.

MG: What about white women and specifically the feminist movement? How was your relationship with the feministic, perhaps not tradition, but theory?

CJ: I had read some key feminist texts, and I considered myself a feminist. I joined a women’s group as a student, but I didn’t find it very welcoming. I was and still am incredibly shy, so perhaps it was as much about my awkwardness as it was about their discomfort with having a black woman in the group. However, the contact with feminist concepts such as “the personal is political’ gave me permission to make the work I wanted to make.

MG: It’s unbelievable. From the feminists’ perspective they saw you also as a divisive force, putting attention to the black issue instead of women’s issue.

CJ: The women’s group wasn’t a space where I could talk about everyday racism, especially if they felt implicated. So yes, they felt the shared oppressions were the ones to focus on.

MG: What about black artists who were already established or, better said, who had a better career, like Frank Bowling? Was he somehow involved in this conversation?

CJ: Frank Bowling was very vocal at the convention on the subject of Black Art and the problem of defining what might constitute black art. I met him for the first time at the convention, I hadn’t known about him or Aubrey Williams or Ronald Moody before meeting him. As student I had only found books on black American artists and my tutors told me they didn’t know of any black British artists. Now I wonder whether my tutors were being disingenuous.

MG: One of the persons you met in that time was Lubaina Himid. She was not only an artist but was also working as a curator and she organized a few important exhibitions in the 1980s; Five Black Women Artists and The Thin Black Line at the ICA. This was a moment in your career that you had shows and you were working with several other women artists, was it very helpful?

CJ: Yeah, it was a great moment and a very exciting time. We would have quite large gatherings of black women artists at Lubaina’s house or at various locations, leading up to exhibitions. It really expanded my contact with other black women artists. It was exciting to take part in those shows. I believed things were changing and was amazed to have the opportunity to show my work so soon after leaving university. Showing at the ICA in The Thin Black Line curated by Lubaina was the high point. Although we were in a narrow corridor and on stairwells rather than in the main galleries, it still felt as if we’d stormed the walls of the fortress!

MG: It seems that you had a good start; what happened during the 1990s? It was an economically difficult period and I could imagine that in that time the YBAs had taken over the whole attention from the press and collectors.

CJ: Absolutely. I did much more teaching in the 1990s than I had done in the ’80s. I needed to make a living, and I wasn’t able to be an artist full time and support myself, so I gradually moved away from exhibiting and from being part of the art circles I’d known.

MG: Where did you teach art?

CJ: I taught at Camden Art Centre and at my local art college which was Hackney College. I did some book illustration. But essentially, I had two children and I needed to have a reliable income.

MG: Having children is another subject that has been also very important and special in your career because you stressed this issue of being a mother and an artist time and again. Being a mother and an artist was not so obvious in the very activistic circles.

CJ: Initially I was very optimistic about being an artist and a mother. I was invited to take part in the exhibition Reclaiming the Madonna: Artists as Mothers (1994). Ink studies of my baby son were selected for the show, though I had wanted to show Afterbirth (1990), a self-study made after the birth of my second son. I remember I wrote a piece for the catalogue entitled “How many do you have now?” in which I challenged the notion that being an artist and being a mother were incompatible. I believed at the time I would be able to juggle it all, but in fact, over time it became more difficult to do that.

MG: Did the children require so much attention that you couldn’t be a part of this network in the art world?

CJ: Yes, is a short answer. After my first child I was still being invited to take quite a few exhibitions, but then it became more difficult to find the time and energy to make new work. Perhaps the major issue was my changing perception of myself. I was always thinking about work but rarely making it.

MG: Did you do a lot of work during the 1990s and end of the ’80s? You had a busy life, you had your teaching, you had your children and you were periodically making works as I understood it.

CJ: At the beginning of the 1990s I had two significant shows. The first was a solo show at the Rochdale Art Gallery [today called Touchstones Rochdale], curated by Lubaina Himid and Maud Sulter. Then, in 1992, I had a solo show at the Black Art Gallery, In This Skin, curated by Marlene Smith. However, the show at the Black Art Gallery was the last major solo show that I had for about thirty years. I had smaller shows as part of open studio events and group shows, of course.

MG: So finally, you had to sacrifice a lot for your children?

CJ: Well, I hate to put it that way. I don’t like to think of it that way.

MG: Sorry for formulating it so bluntly.

CJ: I would say that for me, I couldn’t find a way to juggle everything.

MG: What was the breakthrough moment for you that you started to make art again and become part of, let’s say, the art world you are now?

CJ: Oh, that was entirely down to Lubaina Himid. She had selected Trilogy, a 1986 work for the Tate Britain show Thin Black Line(s) that she was curating. It was a revisiting of The Thin Black Line, that exhibition at the ICA. After that show, she approached me about exhibiting in a group show at Hollybush Gardens that she was guest-curating. The show was Carte de Visite (2015). At that point I hadn’t had a studio for some time. Lubaina essentially provided me with a studio and that allowed me to make new work for the show. Carte de Visite was followed by a solo show at Hollybush Gardens and that led to the show at Modern Art Oxford. The rest is history, as they say!

MG: It’s quite amazing, you had a very long break, and now you’re back.

CJ: it’s a bit shocking to say that [laughs] but I really think, had Lubaina not approached, encouraged and supported me in the she did at that specific moment, I wouldn’t be making the work that I am making now. I don’t think of it as a long break. I believe work was germinating throughout that period – when Lubaina appeared, I was ready.

MG: That’s a beautiful story. We should all be grateful to Lubaina. You have been working mostly on paper. Why this medium?

CJ: Well, initially when I started working as a student I did work for a short period in oiI, which was okay, but I worked on paper not canvas. I like drawing; and I drew primarily in pastels as the mark they gave was so strong and immediate. I liked the way that working on large scale drawing involves my entire body. I worked quite a lot in monochrome in those early drawings but later brought in colour using gouache for its opacity.

MG: Have you always used pastels?

CJ: Almost always. I started working with acrylics about a year ago. I have been using oil pastels and I have been exploring oil paint very recently again, working on bark and other materials. I generally work on large sheets of heavy watercolour paper. Initially, I like to manipulate the paper to change the texture by, for example, scarifying the paper or scratching it with sandpaper, sometimes allowing it to tear. I try to disrupt the surface so that it doesn’t seem so perfect. An impeccable white expanse of paper can be a very intimidating thing!

MG: What about the line? If I think about your work, there’s this wonderful play of lines in it, mark making using line.

CJ: Yes, line is very important to me. It’s my entire raison d’être. I am drawn to earth colours: burnt umber, raw umber; deep tones. People often think they are charcoal drawings, but I could never get a strong enough mark with charcoal. Pastels give an immediate almost indelible mark as soon as you start working with them. You have to commit.

MG: What about another specific element of your work, the sitters? This is quite unusual because the vast majority of artists today work with photographs. I spoke recently also with Jenny Saville, who told me that she couldn’t work with sitters because they require attention from you, and when you work you need the attention for the drawing or for the painting. Don’t you mind having a living person in your studio sitting there and being a part of your environment when you work?

CJ: No, I prefer it because it’s always a challenge to draw from life and it’s much more rewarding. When I work with a sitter on a drawing, I feel as if I’m sculpting the form, as if I’m pulling the form out of the paper. Pastels are very responsive to this approach. Also, through the process I am getting to know the sitter in a different way.

MG: Sculpting the paper?

CJ: In a way, yes. I work on heavy grade 100% cotton rag paper that has a very textured surface which holds pastel well. As the surface is raised and uneven, it feels as if I am working over, around and through the textures of the paper when making a drawing.

MG: Sculpting the paper and then interacting with the sitter which gives unexpected moments – there seems to be a lot of interaction and chance in the process of working.

CJ: That’s right. It’s a much more dynamic process for me. I can really understand what Jenny Saville was saying about wanting the time and the kind of intense focus that you can get when working with photographs and I also work from photographs. However, I prefer working from life. I can be quite shy when I first start working with a new sitter, and even when I am working with familiar sitters there can be an awkward period at the beginning because it’s a long and sometimes difficult process. Once I start drawing, I’m not the same. I’m not looking at them in the same way. I’m not interacting with them in the same way because they become something different to me.

MG: Do you need a lot of time to make it work?

CJ: Yes. I always find it difficult to work out exactly how long a given piece takes. Sitters may to do six sittings or more, and each sitting might be three to six hours long. Sometimes I work from photographs when the sitter can’t attend as often as I would like. I take photos and I work with found images from newspapers and other places. Those works might take a couple of months to be completed. At the moment I work on around three pieces at a time, and that allows me space to form each piece, and time to consider where the work is going and whether I’m happy with the way it’s developing.

MG: It is probably more difficult to rework on paper than repaint something on canvas, isn’t it? You have probably less margin for mistakes.

CJ: Yes, that’s true but then I liked that. When I was teaching drawing, I used to say to my students that the point of my sessions was about trying to begin to trust your mark. I’ve had to learn to trust my mark. That doesn’t mean that my mark always does what I want it to do, but I trust that, if I observe and I follow it whilst I am trying to be as honest as I can, I’ll arrive at some things that at least I find interesting and dynamic.

MG: What do you mean by trying to be as honest as you can?

CJ: Just trying not to get distracted into making something that is just pretty or getting too concerned with exactly replicating the sitter’s appearance. It’s more about what they represent or symbolize for me. That aspiration drives the work and keeps me exploring the way I make marks as well as what I represent. Everything that keeps that process fresh and alive is what I’m interested in.

MG: You said once that you are not interested in portraiture, but you are interested in giving a black person a presence.

CJ: Yes, I am interested in black presence as I am working in a context of absence. Absence for me includes the narrowness of the fields where black people are allowed to thrive, as well as all the areas where we are not.

MG: Portraiture could be seen as a part of art historical tradition. What is your relationship to art history? Do you see yourself as a part of a specific narrative?

CJ: I always loved Rembrandt, Toulouse-Lautrec and Suzanne Valadon; Egon Schiele’s line. I love the drama in historical painting because I still get energy from that. I feel that I am somehow linked to Expressionism; that there’s something about the way that I approach work that is Expressionist, essentially.

MG: You are mostly working with black people, which is of course a very conscious decision, but would you expand it in the future? Would you consider leaving this subject?

CJ: As an art student in Wolverhampton, I needed to see images of black women just to assert my reality. As these images didn’t seem to exist, I had to make them. As I’ve said, black women were virtually invisible. To see a black woman on television outside of the fields of sport and music was a major event in the 1970s and ’80s! Although things are changing, images of black women are still just a drop in the ocean of Western art history.

MG: Things have changed for you. In 2011 you were shown at Tate Modern, you have exhibitions now, you were showing in online Art Basel special project this year – you are getting more and more attention. Can you imagine that your work will be placed outside the context of blackness and women? How strict are you about your own subjects?

CJ: I believe that what I do is make British art. I feel that I am part of the British Art movement and I’m part of British art history, so I hope and expect to be part of those conversations because this is where this work is coming from, black British experience is where this work is rooted. I was really encouraged during the show last year at Modern Art Oxford. Many approached me to talk about the work and their response to it. They seemed to have quite a visceral response to the work, to this encounter with these images of black women and men. I’ve always assumed that the work would speak most directly to black women, but I don’t know now, if that is the case. It wasn’t solely black women who found something of value in the work, though certainly many approached me and said they felt validated by the work. However, it also seemed to speak much more universally. I think that’s where we need to get to. We’re all human beings on this planet who have all these shared experiences and we have to get past the “othering” of black experience. The feedback I received suggests that we are moving in the right direction and that, perhaps, this work can reach very widely.

MG: That’s very beautifully said. Thank you.