Anthony D’Offay

Published: March, 2016, MONOPOL

The legendary English art dealer Anthony d’Offay set up one of the world’s most important art galleries in 1980 representing artists such as Lucian Freud, Gerhard Richter, Joseph Beuys and Andy Warhol. In 2008 he donated 725 works of art in the form of 50 ARTIST ROOMS jointly to Tate Modern, and the National Galleries of Scotland. Since then another 20 ARTIST ROOMS have been created, the latest is a room of sculpture by Phyllida Barlow, the fortieth artist to join the collection. Since 2009, there have been some 40 million visitors in nearly 150 venues across UK, with 600,000 young people taking part in learning programmes. A good moment to speak with Anthony about the artists he worked closely with, his ideas on art, and the changing taste of our time.

Marta Gnyp: How did you start your gallery?

Anthony d’Offay: I started dealing in books when I was seventeen. When I was 21 I got a small sum of money as compensation after an accident. I was able to buy a very interesting poetry library and became so fascinated by its books that I produced a catalogue which was a big success. When you are studying at university and you manage to do something successful outside your area of study, that tells you in which direction you should go. I became a full-time dealer in rare books and drawings. I moved to London at the age of 23, and opened a tiny gallery when I was 25.

MG: I read that it was very successful from the start. Why?

AdO: I think because we were producing very good exhibitions. I put together shows such as The Influence of Whistler on English Painting; The English Friends of Paul Gauguin; Dream and Fantasy in Victorian Painting. But when we made an exhibition of Drawings by Hokusai, for the first time we got great reviews.

MG: Where did you get the drawings?

AdO: I worked on it intensely for 2 to 3 years. I believe in proper research. I worked with Jack Hillier, a great friend, who had written the standard monograph on Hokusai. It was a very exciting thing to do. There was a show at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1951 with drawings by Rembrandt, Van Gogh, and Hokusai, three of the greatest draftsmen of all time. It is rather difficult to do a selling show of Rembrandt or Van Gogh so I wanted to see what we could do with Hokusai. It was a beautiful show. People came from Japan to buy works.

MG: So at the age of 28 you became a specialist in Japanese art?

AdO: We did a show entitled Actors and Courtesans, The Japanese Print 1770–1800, with very rare prints in it. I remember a collector who flew from Japan to see the show. Then in a very non-European way he said “I need time with you” so we sat down for three hours and talked. Then he stood up, bowed, and said: “It is an honor to buy these prints from you.” A wonderful idea, trusting the dealer rather than the work of art.

MG: You were building your reputation?

AdO: As time went on I felt that we should try to open a big contemporary gallery.

MG: Why did you want to switch when you were doing so well?

AdO: Because London needed it. I was friends with several artists. I started representing Lucian Freud in 1970. Through him I also made friends with Francis Bacon whom I saw often. I was beginning to realise it was my duty to try to bring the best artists in the world to London.

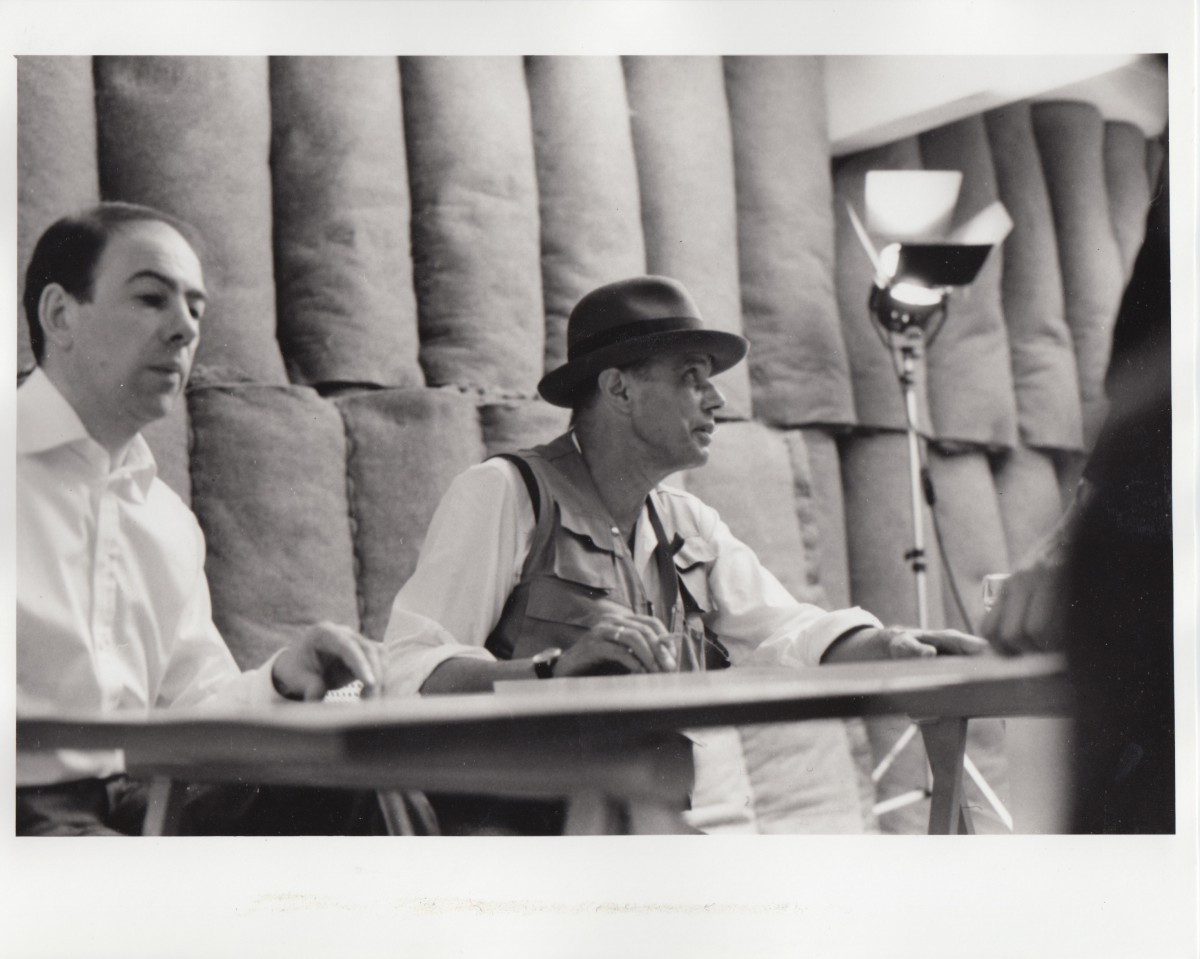

MG: How did you find Beuys?

AdO: He had a big show in Rotterdam of drawings belonging to his friend Heiner Bastian. I went to the show and met Beuys for the first time.

MG: Why do you think Beuys was such an important artist?

AdO: If you think of the history of modern art, we had Abstract Expressionism, then we had Pop Art, followed by Minimal art and then Conceptual art. Then in 1981 the exhibition New Spirit in Painting in London pointed everyone in a new direction. But it was Beuys’s retrospective at the Guggenheim in 1979 that was the real moment of change. It said categorically to New York that there was more in the world than just American art.

MG: How did Beuys convey this message?

AdO: Through a 1977 sculpture called Tallow – 22 tons of fat brought into the museum by removing one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic windows. His sculptures of fat and felt had something shamanistic about them and were often connected to performance. Beuys had a very profound preoccupation with the education of young people and the development of their creativity. He strongly believed that we have a real obligation to empower each other. Beuys was also one of the initiators of the Green Party. He had an unforgettable presence; you were very conscious when he was in the room. I remember Richard Hamilton telling me that he had an exhibition opening somewhere in Germany, and it was a big success. Then Beuys, who was his friend, arrived. “God, I wish he hadn’t come,” Hamilton told me. All the cameras, all the attention turned to Beuys.

MG: How come he was so charismatic? Was he manipulating people?

AdO: He was like Andy Warhol; both of them were almost killed. Both of them had a near-death experience: Beuys when his plane crashed, Warhol when he was shot. If you die and you come back from the dead, very often you change as a person.

MG: Do you believe Beuys’s story about the plane crash and his being saved by the Tatars?

AdO: If you didn’t believe it you could ask him to take off his hat and look at the scars on his head. It wasn’t a comfortable sight. If you fall on your head from an airplane in the Crimea you are lucky if some Tatars pick you up and nurse you back to life.

MG: And after he recovered he felt he had a mission in the world.

AdO: A lot of his ideas had to do with healing: he dreamed of healing the world. Think of PLIGHT [a big installation by Beuys first exhibited in the gallery in 1985 and now owned by the Centre Pompidou]. The word ‘plight’ means three things: a promise as in “I plight my troth”; a plight is also a difficult situation; thirdly, there is the French word ‘plier’ to fold, just as the felt in the installation was folded. However, the promise was the most important aspect. The sculpture had to do with the healing of the gallery, which had been suffering from noisy building work. Beuys saw it as a muffling sculpture. As a visitor you were immediately taken aback at the silence, the smell of felt, hearing your heart beating, listening to your body.

MG: Would you say that Beuys was the most charismatic artist you worked with?

AdO: All artists unique and extraordinary, you only have to think of Freud, Beuys and Andy Warhol. They were all so different, so brilliant, and so strange that you could truly say that there was nobody like them.

MG: All three of them lived their lives through art.

AdO: They considered art as the most important activity which could change the world.

MG: How did it work in daily life?

AdO: Beuys said to people: everybody is an artist, meaning everybody has to develop the creativity of an artist.

MG: On the other hand his charismatic appearance made people think differently, that they could never be like him.

AdO: When he went to the openings of his exhibitions, he would always immediately talk to the shyest, youngest person in the room. He was trying to make the world a better place, especially the world recovering from the Second World War. I could understand it because I was born in 1940 and I remember the war. I remember the bombs falling, I remember seeing a German aeroplane which had crashed at the end of our street.

MG: How did you experience the war?

AdO: For a young child the sound of sirens – warning for a bombing raid – was very exciting. I didn’t feel fear, but a big adventure. We all ran to the air-raid shelters which were at the bottom of the garden. We sat there, made a cup of tea in a concrete box, and listened to aeroplanes bombing until it was over. Immediately after the war, my father was a surgeon in the British Army on the Rhine. I expect he was putting people back together after air-raids or people who had houses collapsing on them. I noticed, however, that the war had a very good effect on my parents. When my father came back home for a weekend, my parents were extremely loving to each other and to us. I thought the war was wonderful.

MG: What about the idea of Germany as the enemy?

AdO: We had prisoner-of-war camp within walking distance of our house. Through barbed wire I could see rather unhappy looking men on the other side. At the end of the war all the reckoning with Germany started: the Holocaust, war criminals, Eichmann and all those things. It deeply affected Baselitz, Kiefer, Richter and Polke. They all felt strongly the experience they lived through and always felt influenced by it. Being German affected all of them, but none more than Beuys. He actually took part in the war.

MG: Did Beuys speak about his experience with you?

AdO: He was a POW of the Coldstream Guards Regiment. So I mentioned to him once that probably everybody had looked after him very properly. He said: “They were fantastic. Really wonderful. There was only one problem.” When I asked what that was he replied, “No food. I used to have a pair of scissors, and cut grass with the scissors and try to cook it; not so much fun.” I don’t think he would ever have said anything about it if I hadn’t asked him. Nobody was tortured, nobody was shot, they were just not given any food, only just enough to survive.

MG: Did the war play a part for other artists as well?

AdO: I remember Lucian Freud saying to me that he had great fun going around Berlin painting swastikas on the walls. Lucian was always a bad boy. If you made a rule he was going to break it as quickly as he could.

MG: Did this attitude get him into trouble?

AdO: When he was taken on by the Acquavella Gallery in New York he had racing debts of 2.8 million pounds. But then he said to me: “You know what is more exciting than winning? Losing. Because then you need to mobilize your energy and be creative.”

MG: Beuys wasn’t afraid to get into trouble either.

AdO: Beuys was dismissed from the Düsseldorf Academy because he wanted to allow all students who wanted to come to his classes. You can imagine how annoying it was for the art school and for other professors. Then he said: “After World War One there was a young German who wanted to join the art college in Munich but was refused. If Hitler had been accepted by professors like me, the history of the twentieth century would be somewhat different.” Beuys really knew how to reach the heart.

MG: How was the relationship between Richter and Beuys?

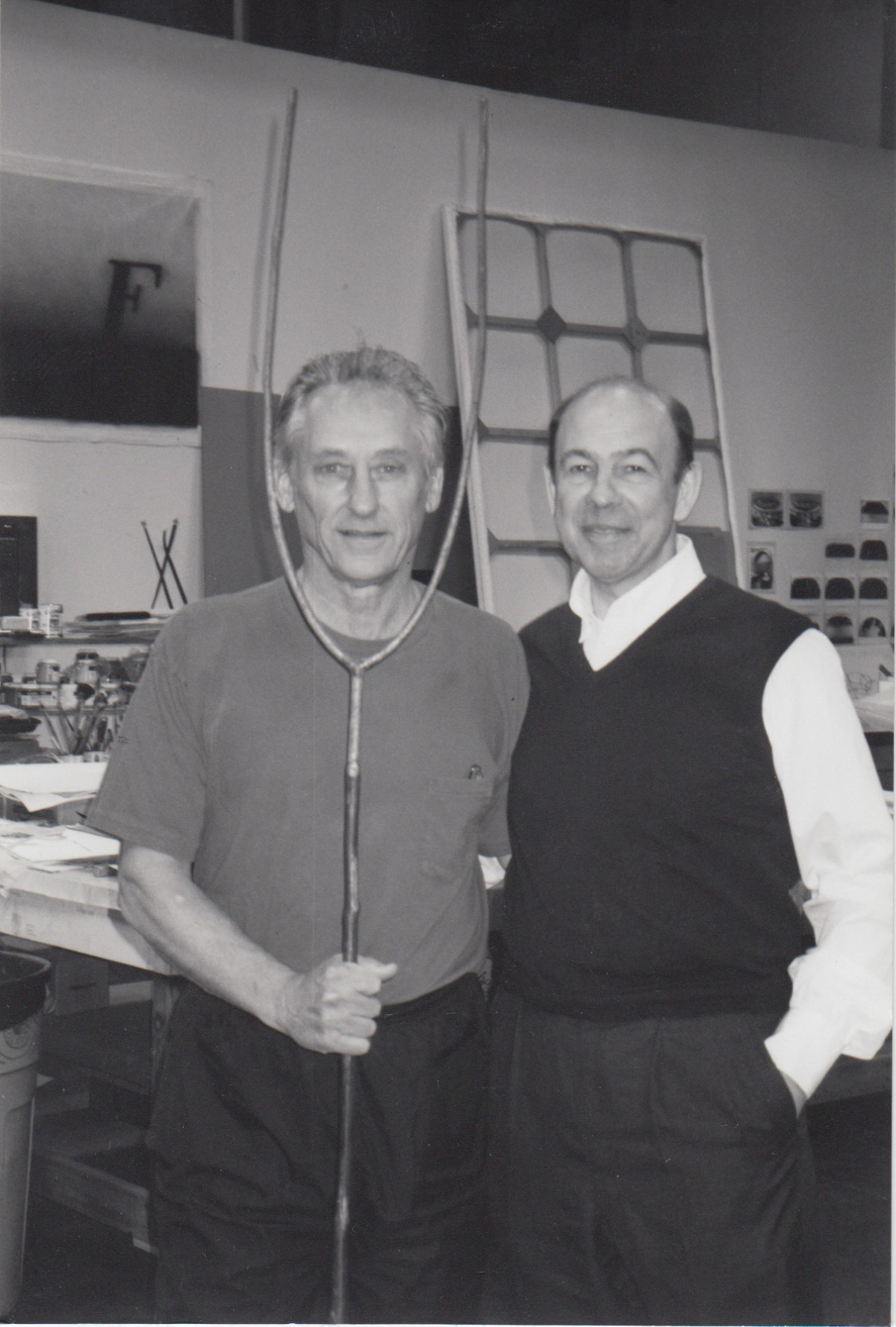

AdO: Lord Snowden took a very beautiful photograph of Beuys’s face with some felt fibres from the PLIGHT installation stuck to his hat. Years later I was in the Richter studio and saw this image framed. I told him that I didn’t know that he was close to Beuys and cared so much. Richter said an incredibly interesting thing: “No, I had to take care, because you could start to believe his theories, change your mind and become a follower of Beuys. I didn’t want to change where I was going. I always had to keep a distance.” That speaks very much about the power of Beuys and his personal presence. People in some sense, men, women, young and old, fell in love with him. Kiefer came closest to knowing him well.

MG: What about Beuys and Warhol? Warhol’s idea about art was completely different.

AdO: They saw that each of them had a great power but that power was completely different from their own. They were slightly amused with each other, but they also knew that the other was the real thing, a great artist. They respected each other.

MG: What did you think about Warhol’s fascination with commerce and “business art”?

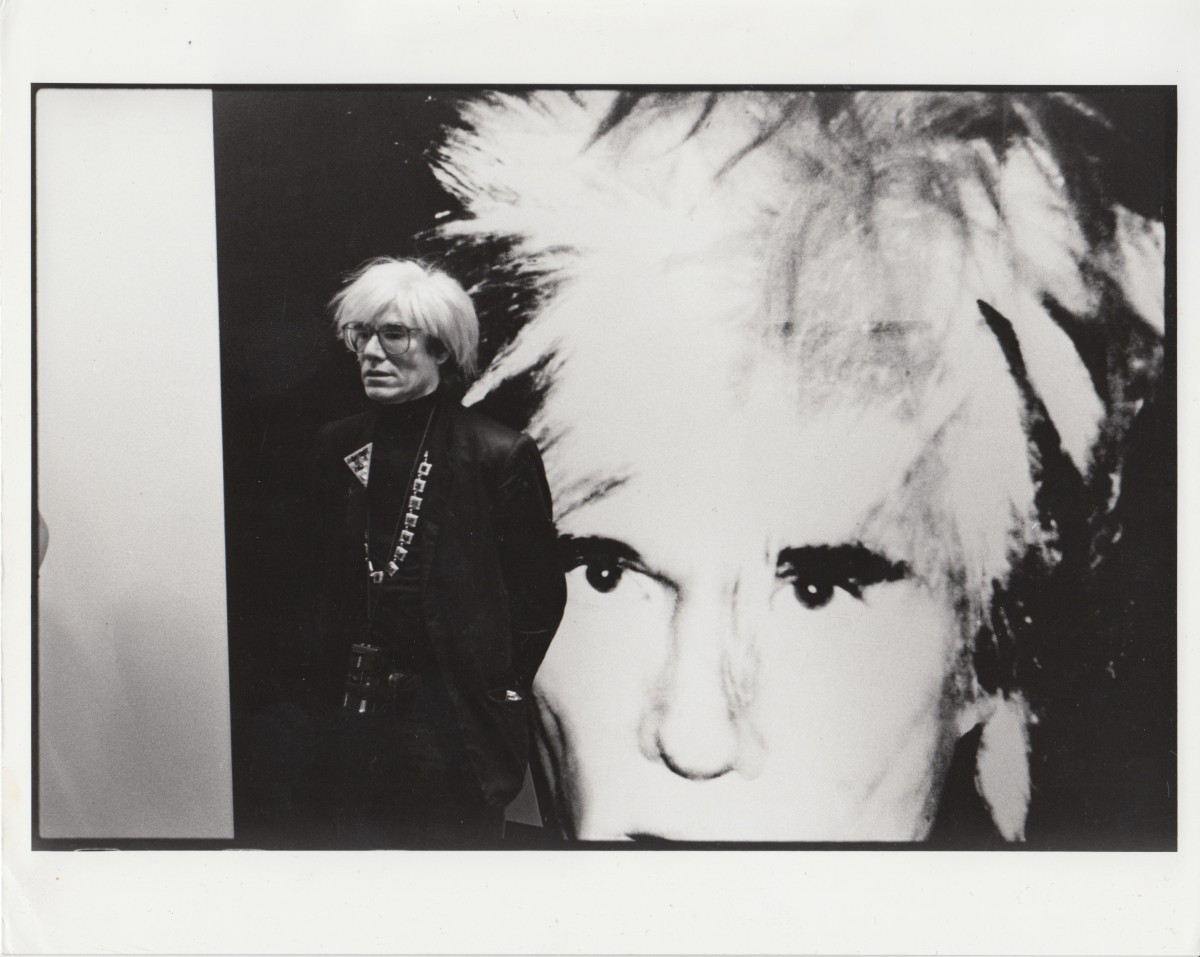

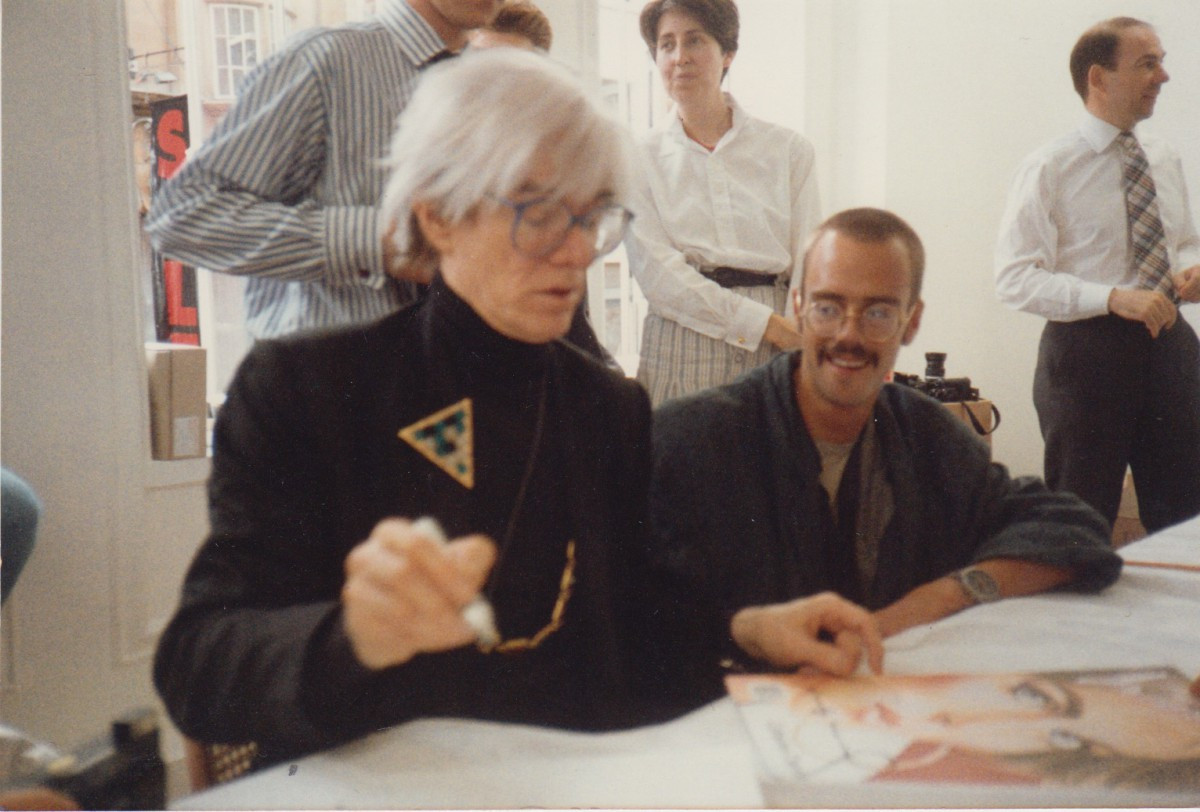

AdO: Warhol liked to say things in a provocative way. He always wanted to give the worst possible answers and say the worst possible things. Normally, we do the opposite. People hated it when he started to paint money but it kept Andy amused. He liked to watch how people reacted. When we wanted to do an exhibition in London with him and I asked him what he would like to show, he answered: “Whatever you want. You tell me and I will do it.” No other artist in history would say that.

MG: Was he testing you?

AdO: He was trying to make me come up with a good idea. I suggested a self-portrait and that was what we did. I thought that it was very important that he got a show with good reviews because around 1980 he was not popular with art critics; everybody hated those guns, knives, and dollar signs. I wanted people to say that here is the great artist at the height of his power.

MG: Did you achieve it?

AdO: Yes. We sold many from this show immediately to museums, including a large self portrait with camouflage. The idea “you tell me, I’ll do it” was an extraordinary one.

MG: Around this time you also started to work with Kiefer.

AdO: Our first show with him was in 1982/83. We were already working with Beuys who was extremely important to him. Kiefer said that the time that he spent alone with Beuys in Düsseldorf was the most important in his life. Thus Kiefer and I had something very strong in common: we both admired Beuys. When we did the show Anselm was delighted because works of art went to museums. He has always been very conscious of the importance of museums. He is also an extraordinarily generous person; he donated great works to ARTIST ROOMS.

MG: Kiefer seems to be gaining momentum now. His importance and place in art history seem to be not only generally accepted but also growing. Was it not difficult for him in the past to be in the shadow of other artists, like for example Richter?

AdO: I don’t think that Kiefer has ever been in the shadows. Richter was rightly recognized as one of the greatest painters of the twentieth century and his prices doubled, tripled, quadrupled, whatever it was. Taste changes all the time; artists’ reputations and the relevance of their work change all the time. It is a very interesting phenomenon. Another example is Bruce Nauman who has suddenly appeared as a giant of the twentieth century; not just a very interesting or extraordinary artist, but a modern master.

MG: Do you have an explanation for these sudden changes in taste?

AdO: Part of it is politics, what happens in the world and how people feel. For example Louise Bourgeois has with time become a great twentieth-century figure. She was able to do things that no man had ever attempted, like the giant spiders and the cells. Her ideas were liberating and beyond male thinking.

MG: You mean that we needed to go through the 1980s, and shifts in thinking about gender and identity thinking, to be able to recognize her greatness?

AdO: That’s right. And then you need great exhibitions. Frances Morris did a magnificent job with curating the retrospective of Bourgeois in Tate Modern in 2007. I saw works there that I had never seen before, which I found incredibly moving. That was the first time I appreciated what a genius Louise Bourgeois was. It was then that we met the wonderful Jerry Gorovoy who looked after her during the last twenty years of her life, working with her every day, calming her down, cheering her up, making sure that the bronzes arrived, and that everything was done properly.

MG: Do you think in terms of male and female when looking at art?

AdO: What I really care about is that artists like Louise gave confidence to many women. This empowerment seems to be very important. Think what a different world it would be if half of the world’s leaders were women. Couldn’t we do with some women in North Korea, with some women in the Middle East or in Russia?

MG: You never represented Louise in your gallery.

AdO: I’m told that she wanted us to represent her, but at that time we were representing thirty of the world’s greatest artists. It is always very difficult to take on more artists. However, we now have quite a lot of women in our ARTIST ROOMS: Agnes Martin, Vija Celmins, Ellen Gallagher, Jenny Holzer, Diane Arbus, Louise Bourgeois, and Phyllida Barlow and Francesca Woodman.

MG: Have you observed the relationship between the artists and their public?

AdO: In a way there are two sorts of artists: the artists who want powerful, rich, and important people to see their work, and the other sort of artists who want the public to see their work.

MG: So who would be in the first category?

AdO: [laughs] You know how to answer that question.

MG: I would love to hear it from you.

AdO: I think that artists have a special relationship to money and power. Making works of art is a sort of generosity in itself. That is to say creation can be a painful process for many artists. Giving birth, with all its problems, is exhausting: you give away a part of yourself, it is often painful and can take a long time. And then comes the question how will you present the work to the world.

MG: One needs courage to be a great artist. During the 1990s painting went out of fashion and was declared dead. How was it for your artists, many of whom were painters, to go through this period?

AdO: They were all great artists and great painters. Kiefer said about Koons with whom we organized a show in 1992: “I don’t like his work but I think it is a great idea to do the show.” What he meant was that he understood that this is art from now, from this time. You can have seven years basking in the light of success and then things change in the history of art. That doesn’t mean that an artist stops being an artist but rather that he or she very often has to spend fifteen years being that same artist and waiting… Like Kiefer, who has waited for years for his great retrospective happening now at Centre Pompidou.

MG: Do you think they had a difficult time?

AdO: Absolutely. You have to paint, when everybody is looking at the YBAs and Koons.

MG: What was the strength of Koons?

AdO: To put it simply, he sees the good in everything. He picked up ‘banality’ where Warhol left off. He gave people what they wanted in the same way that Warhol did. We started to work with Jeff Koons shortly after his Banality exhibition in 1988. On the occasion of our 1992 show we published the Jeff Koons Handbook and sold over 50,000 copies in a year. His works and statements were something nobody had ever heard before [opens the book and reads]: “In the Large Vase of Flowers there are 140 flowers. They are very sexual and fertile, and at the same time there are 140 assholes.” How about that?

MG: What did you think about the YBAs?

AdO: We were proud to show Ron Mueck and Rachel Whiteread. We did a lot to place Rachel’s work in museums. Damien, who worked for us painting walls and installing sculpture when he was a student, is today well represented in ARTIST ROOMS.

MG: Many important players in the art world once worked with you. Why was it so interesting for them?

AdO: They could earn a bit of money and spend time with Twombly, Warhol, or Koons. We were very much a team. We had a lot of meetings and I didn’t allow anybody to attend who did not come up with ideas. I wanted everyone to be creative. I was over 50 and wanted to hear what people in their twenties had to say. Sadie Coles, Gavin Brown, Matthew Marks and Lorcan O’Neill worked all in the gallery. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York kindly invited me some years ago to give the Stieglitz lecture. The director, Tom Campbell, very kindly introduced me by telling the audience that his very first job was as an intern with us in the early eighties.

MG: Did you go to visit collectors?

AdO: For me artists and museums were of essential importance. For collectors I had an excellent sales team. You can’t do everything yourself. I travelled a lot. I would go to New York, Los Angeles, Sydney, Tokyo, and then back to London. If you visit Australian museums you will find masterpieces by the artists we represented.

MG: Your strategy was to go to countries that were not completely included in the Western art network.

AdO: It seemed to me that we were providing a service, which kept us in touch with the rest of the world. I was asked to organise the German part of the Sydney Biennale one year; we focused on Beuys, Polke, Richter and Kiefer. In Australia they have wonderful museums and they are very happy to collaborate.

MG: This is a slightly different approach to, for example, Leo Castelli who seemed to be giving a lot of attention to collectors.

AdO: Castelli was a great friend and it was an honour to work with him. He had a very special approach to communication. I remember an occasion when we were sitting in his office in New York and he said, “Jasper Johns hasn’t had a show in London yet. By the way he is coming for coffee in ten minutes.” And then the show was fixed.

MG: If you would start a gallery today, would it be possible to do it in the same way?

AdO: Impossible. I don’t think that the gallery that we had could exist in the world today. The idea that you spend all your time trying to sell works to museums is probably completely outdated. In 2001, the last year of our gallery, fifty-five percent of our sales went to museums, which wouldn’t be thinkable today. Museums are slow payers. The idea of different countries is gone – today everything is international. We had a mission: to have a great gallery, to get people to come to London to see contemporary art, and to change people’s feelings about what they saw. All the young artists grew up seeing the shows we produced. They realised that they were witnessing art history.

MG: Do you think that the omnipresence of the fairs has changed a lot?

AdO: In the old days the artists didn’t want to be at fairs. What is also very strange is that in the old days at the openings of shows you could barely get in through the front door, now nobody comes any more. Collectors are all waiting for Frieze, Basel, and other fairs.

MG: You had excellent contact with museums, what about auction houses? Were you supporting artists when there was a work at auction?

AdO: Yes, we bought works at auctions if that seemed like a good thing to do.

MG: Have you been following works that came from your gallery at auctions?

AdO: Of course. The most expensive contemporary work that sold for 57 million dollars was the Balloon Dog by Jeff Koons that we sold to Peter Brant.

MG: It was Peter Brant who bought it from you?

AdO: He also has Koons’ Puppy in a field in Connecticut. It would be very nice if he would give it to the Met. Peter Brant could do something wonderful for the city of New York. The A/P of Jeff Koons Puppy, which we sold to the Guggenheim in Bilbao, is a national treasure!

MG: You are very much in favor of cooperating with public museums and donating works.

AdO: Public institutions have always been of great importance to me. When you think for example of Berlin and Hamburger Bahnhof – the Marx Collection is a great treasure and, God willing, it will stay in Berlin. Marx has masterpieces by Warhol, Twombly, Lichtenstein, and Beuys, which are of the greatest importance to Germany and belong in that country. The same is true about the UK. Very often we have great museums but they don’t have the necessary acquisition funds. How is the Tate going to make great exhibitions without gifts? With ARTIST ROOMS, we were trying to think what is important for this country.

MG: What about private museums?

AdO: Private museums can add greatly to the cultural landscape of the world. It was a tragedy for France and for Paris that François Pinault decided to set up his museum in Venice instead of the Île Seguin in Paris, as he had originally planned. It would have been so good for the Centre Pompidou to have another big institution for contemporary art in Paris. I remember the moment when I read this, I was in New York – I burst into tears. I think it would have changed Paris in a very positive and exciting new way.

MG: Do you think that competition between museums works positively?

AdO: Look at the New York museums: there is a lot of competition between the Metropolitan, the Guggenheim, the Whitney, the MoMA, the New Museum – a lot of cooperation as well, but it is competition that keeps everybody on their toes.