Andrei Roiter

Published: July, 2012, L'Officiel Hommes #4

The artist Andrei Roiter divides his time between Amsterdam, New York and to a lesser extent Moscow, the place where he comes from and where his artistic vision and identity has been formed during the time of great historical shifts.

MG: The Dutch public knows you in the first stage as a painter.

AR: This is an illusion like many other illusions about me. One of them is that I’m a serious, disciplined man that I’m not, and another one is that I can paint very well. I don’t know how to paint so this is why I’m trying so hard.

When I entered the space called painting, there were so many things to learn. I got sucked in the learning process and got seduced by the amount of opportunities this medium offers. But in a certain moment you have to step out.

MG: Because you became too much a painter?

AR: I have never wanted to be sucked in or become dependent on one medium, be it sculpture or photography or installation.

MG: Why not?

AR: Because being an artist means being an outsider who is breaking the rules. You need to establish your own rules that fit the best with your perspective, your character and your speed of consumption. There is no recipe; you have to find it yourself. So in a way your life is a research to find out what you do the best.

MG: And this research requires sometimes a change of the direction?

AR: In a certain moment you are going to feel stuck, claustrophobic in the space you work in and you need to experience something else. This is why I travel. This is why I’m spending more time with my notebooks than with canvas and brushes. I paint canvases that are related to my thinking. But it takes me months to decide what to paint.

MG: I have the impression that you don’t want to commit yourself to one medium not only in the field of art but in general, you don’t want to commit yourself to one place or one clear concept. The concept of Andrei Roiter is that he always escapes from one single concept.

AR: Correct. This is a naïve and childish attitude, but a very strong one; it is my friend and enemy at the same time, but you have to become friends with your enemy. If I feel too much pressure I want to escape. I realized some time ago that it is a part of my personality, although you can also explain it as being confused and not focused enough. I have to live with my personality. You can be successful in life only when you are honest with yourself about your strengths and weaknesses.

MG: The self-knowledge and self-awareness are for you the main principle of success?

AR: Yes, together with being open-minded and flexible. That is the principle to which I have committed myself the most.

MG: Do you think that the artist has a very special position in the society?

AR: I don’t give the artist any privileged position. The Artist is a strange sort. People are becoming artists for many different reasons: for example to be on the stage in the spotlight or to be glamorous and famous. In my case it is definitely the issue of self-therapy. As a little child I wanted to live the life of a hermit.

MG: Lets then go back to your Soviet childhood time. When did you decide to become a hermit and when did you decide to become an artist?

AR: We have to talk about my family to understand it. I was born in the family of two young engineers and nature lovers who just finished university in Moscow. Both their fathers were arrested in Stalin’s time and sent to Gulag in Siberia. After spending 15 years in the camp and after the death of Stalin their wives and children were allowed to visit or join them. My parents met there in the local school for children of prisoners. They went later on to Moscow, became students at the university, became a couple and soon after I was born. At that time both my grandparents were still alive, and the whole family – probably as a self-therapy – was involved in nature loving. My parents were working as engineers, but every free moment we would go to the forest. There is a photo of me, sitting in a knapsack behind the neck of my father when he is on the skiis – I couldn’t walk yet. For me being in the forest was more natural than being in the city, although I was living in Moscow the city of 11 million people.

MG: Did you also love the nature that much?

AR: When I was in school in the first grade the teacher asked us to write a text what we wanted to become in the future. I wrote just one sentence: I want to live on an island, alone or maybe with a friend. She crossed out my text and said: you can’t think about such a horror. And that convinced me that I should be quiet about my imagination and not tell anybody what I really think. Also I would dig a hole in the ground behind my parents’ house stealing cans of soup from my mother’s kitchen and trying to prepare myself for the solitaire existence.

MG: When did you connect your solitary existence with the idea of artist?

AR: I spent a lot of time alone with my drawings. And that hobby became serious. But when I said to my parents, as a 14-year old, that I want to become an artist they said “this is not a profession, you should study something real”. So I went to study architecture just to make them quiet but my heart was not there, I already met some other kids and older artists whose lifestyle I wanted to have: you had a visible job because everybody was obliged to have it, for example you worked in a post office or made illustrations. But this was only to support your true “unofficial” interests, making drawings or writing a poem.

MG: You landed in the circle of the Moscow Conceptualists.

AR: Firstly it was the circle of the dissidents. I met people who looked like everybody else but in reality they were living underground: waiting to leave the country or artists who decided not to emigrate but live an invisible life.

MG: This invisibility was exciting for you.

AR: Exactly. I wanted to be invisible as well like a cockroach, to have a freedom to do whatever I want and have friends with the same orientation.

MG: You were reading a lot, drawing a lot?

AR: Yes, we were meeting in the evening and having little parties. I started to participate in underground exhibitions when I was 18; artists with whom I was showing were in their 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s. They were very friendly and supportive.

MG: Being an artist was not a profession but a lifestyle?

AR: Especially in Russia at that time. You made art for yourself and for your friends. Once in a while you sold a drawing to a stranger.

MG: So how did you live?

AR: I had a job in the post office and in a bookshop and my last job was as a night guard of an abandoned kindergarten. It was a gift from life: 25 empty rooms in the heart of Moscow, next to the KGB. With a garden full of apple trees. Together with three other artists we had to guard it during the night. We were sitting in one room sipping on our tea and then of course discovered the amazing big rooms. We started to use them as our studios and to invite our friends during the night, make exhibitions or read poetry. It became an art center. During the day it was quiet, during the night behind these closed windows was magic, Bulgakov.

We didn’t form any organized movement, we didn’t have a lot in common, didn’t have any manifesto, but people started to visit us and call us Kindergarten. We entered history as the Kindergarten group.

MG: The authorities didn’t know that you were making exhibitions there?

AR: When they started to watch us it was the beginning of perestroika, 1985.

The borders went open and all kinds of people started to visit Moscow: collectors, museum curators and journalists. They were firstly going to Kabakov and then asking about young artists and Kabakov was sending them to us.

MG: It must have been crazy, all of the sudden a completely new world opened up.

AR: It went gradually. I was in this underground circle for years at that time already. When foreigners wanted to see something, some people were ready for this some not. Kabakov was very well prepared: he was showing his works, books he made, concepts he had. Other artists were making one work per month since before we didn’t have the art world as such. A lot of them were just drinking tea and vodka. People, who were prepared immediately got the opportunity to show their works abroad.

MG: How did you experience this period?

AR: I was considered the representative of the Kindergarten group. Looking back we were all very naïve and too excited. Most of us didn’t have proper studios and proper materials, we didn’t think about making museum works. But then came the demand, for collectors were coming. Things became different some artists started producing 10 pieces per day.

MG: You were part of these enormous historical shifts in the Soviet Union not only as artist also as an individual.

AR: Sure, and you can analyze me from this perspective. What happened to me is the result of these big shifts and transformations. One moment it was open, then closed, one moment they seduced you then disappointed you.

MG: Did you learn anything from these shifts? That you are an instrument in the hands of the history?

AR: Yes. I always have had the idea that I’m going to survive by myself. I don’t know who put this idea in my head, somehow I knew that in difficult moments nobody is going to help me and that I have to do it on my own.

MG: Is this idea true?

AR: In my life I cannot complain. I met many people who were nice and helpful, I learned a lot from other people. But when it comes to a collective mythology I’m blocked, I have such an aversion against everything collective that I catapult myself from the crowd. When things are becoming collective, I have to go. I have always made my mind on my own in a kind of slow way. As soon as I was able to travel abroad I sensed that this idea of being treated as a Russian artist to represent perestroika art, the unofficial art, seemed to be artificial. I wanted to experience how it is to be on my own. It was not a strategy, it was more a curiosity. Looking back it saved me. The interest for Russian artists went down; people who were interested in Russia became interested in China or India. Since I was not part of this circle alone it didn’t affect me. Collectors were not buying my work because I’m Russian. Even now the Russian collectors don’t particularly like my work because I’m not Russian enough.

MG: Still, there is something Russian about you, what is it?

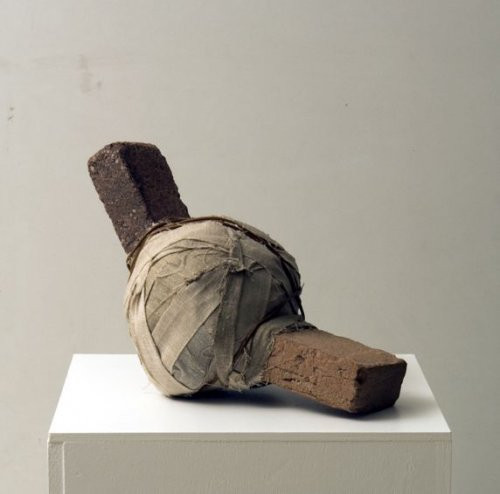

AR: I spent my first 30 years in of my life in Moscow. Most of my ideas, principles, conditions and forms are from there. When I came to Brussels, my first trip abroad, travelling 3 days by train I was 30. You are open-minded, you want to learn, but some part of you is already formed. What I experienced in Russia was the challenge of making art when you don’t have proper materials or even a studio, but you still want to make something beautiful, to experiment. This I did in Russia and I keep doing it even now. Most of my objects are made from recycled materials. It is not an aesthetical choice but more a commitment to the belief that you can do a lot with very little. And how much you can do, how fare you go it varies. Say less, tell more.

MG: Your objects and the spaces that you show in your works are often mysterious and dreamlike.

AR: In real life I’m very attracted to abandoned houses and rooms: you see only a few items on the floor, you ask yourself what happened here? In my works I suggest what kind of life was taking place there.

MG: Is your attraction for abandoned spaces coming from the Kindergarten time?

AR: Abandoned spaces are interesting because you feel the presence of somebody but you know too little to reconstruct what was going here before. You need your imagination.

MG: Abandoned spaces means also loneliness. Is loneliness the existential characteristic of the human being?

AR: I’m attracted to the idea of solitude, which is one of the main characteristics of being an artist; you spend a lot of time on your own. I’m interested in people but I’m interested in seeing beyond them and what they leave behind. If I find an object I’m thinking who made it, in what kind of state of mind? “Show me what you have and I will tell you who you are.” So my objects are like portraits: symbolic, metaphorical representations of certain human issues.

MG: What are the important human issues at this moment?

AR: I believe that we are living in a time of catastrophe.

MG: Which catastrophe we are living in?

AR: Ecological, spiritual, political.

MG: More now than it used to be in the past?

AR: If you zoom in in the history of the human civilization we were living permanently in a catastrophe; it just manifested itself differently. But today’s ecological catastrophe is different and like never been before. We cannot blame only ourselves because the roots of the problem are far away in the history.

But the question is: what is wrong with us? Why are we so self-destructive?

MG: In this sense you are a very classical artist because you are addressing the big questions of what does it mean to be human?

AR: I want to put the questions to the audience – not didactic or simplistic – but I would like you to think about it. And of course there will be different answers and different interpretations of what someone sees according to his or her life style, life experiences, education etc.

MG: Do you care about your visibility for the public?

AR: I want to be visible only through my work. There is a big difference with the young artists whose concept of being visible requires serious work and social skills. You need to go out, make phone calls, meet the right people and connect to the society. I’m aware of it, but it’s not my cup of tea.

MG: Don’t you think that being a celebrity is a part of strategy that is necessary to get recognition for your work?

AR: It looks that way more and more. I’m from another world. I want to put everything we talk about, all my thoughts in one single image. For this you need a focus, you cannot do it between parties.

MG: For your concentrated images you often use symbols: cameras, suitcases or flags. Do you think that it is easier to communicate with the viewer through the archetypes, even if they are very personal?

AR: A certain part will always remain obscure, not that obvious and one-dimensional. There is something very verbal and not verbal, there is a suggestion of a certain narrative but at a closer look it appears as a fragment of something larger.

MG: Are you playing with memory? With nostalgia?

AR: One nostalgia, which we all know, is the nostalgia for our childhood. As for me, I remember only good things; maybe that is where the nostalgia is coming from. Otherwise I have a problem with nostalgia, it suggests that before was better. I don’t want to go back. Naturally, we absorb things the best in our childhood; it becomes our foundation and background. There is plenty of irony, even parody on the idea of nostalgia in my work.

MG: Is irony something Russian?

AR: Sure. If you live life through emotions the world looks very sad, if you live your life through your mind the world looks comic. I feel in-between, I like tragicomic, I like Beckett, and Charms. This is that sad humor and its spirit that I admire and wish to cultivate.

MG: Do you think that the audience understands what you mean?

AR: When people are laughing or smiling at my openings it means good, if they start talking about nostalgia and sadness, that is not what I want people to see. There is sadness in my work but it is not the priority.

MG: Lets talk about your first trip to Brussels.

AR: It was a gift! The fate didn’t send me to New York, Paris, London or Berlin, like most Russian artists, but to Brussels. Brussels is the place of Magritte, Broodthaers, of the surrealist tradition. It is a quiet place.

MG: Did you go there for an opening?

AR: Yes, a show of Russian artists. I had a tourist visa for 3 months. I thought I would come back in 10 days. But at the opening I met a collector who asked me about my plans. He said: “there is an empty apartment here and I can help you to buy materials”. An eight- rooms apartment in the center of Brussels full of books!

MG: Did you speak English at that time?

AR: A little, in Belgium English was not that common at that time so we could speak at the same level. I spent 3 months there making paintings and drawings, by the end of my stay the collector organized an apartment exhibition, something I knew from Moscow. He invited his friends, I knew already some gallerists from there. We sold some works; I made some money and went back to Moscow as a totally different person.

MG: What did change in you?

AR: I realized that I could survive even with a poor language and that I can work totally alone without my family, in a foreign country. It made me optimistic and strong. After that I went to many other openings in Italy, Austria, Germany and in a certain moment I stopped going back to Moscow because my life was outside Russia.

MG: How did you find Amsterdam?

AR: When I was in Brussels I visited a small art fair in Gent and around this time I bought myself a small camera. Excited and confused I wore my father’s heavy winter coat, and at the parking place I discovered that I lost my camera. I went back trying to recall the trajectory. One unshaved skinny guy gave me my camera back. To thank him I made a little drawing for him, signed it and walked away.

A year later when I was in Italy I got a telephone call from Moscow that a Russian lady who came to Amsterdam to promote Russian art was told in one of the galleries that they were not interested in Russian art but they were interested in this man, and they showed her my small drawing.

MG: Which gallery was it?

AR: Aschenbach. So the Russian lady called my wife to tell her that this gallery was looking for me. I thought it was nonsense because I was never in Amsterdam before and didn’t know the gallery but a part of me was curious so I drove with someone to Amsterdam. What happened was the assistant of the gallery, who found my camera explained me that after I left Gent he searched for me in catalogues of Russian artists and became interested in my works. He invited me here; rented me a studio and apartment and invested money in me. My show in Amsterdam went very well. My next show was in Basel during the Venice Biennale opening and the Art Basel Fair. I got a lot of attention and Aschenbach made a petition to the police asking permission for me to stay one year in the Netherlands. He presented me as an international artist who will support himself. In this first year I paid taxes and proved that I can take care of myself.

MG: You were really living a life of a nomad.

AR: It was very easy for me. I could put all my belongings in one suitcase.

MG: Did you like to live this kind of life?

AR: I loved it. When I was a kid I was looking at the hippies among the dissidents and I wanted to become one. I wanted to have long hair, to live without anything and to travel. The idea of living with nothing was not scary.

MG: So you were living your child dream.

AR: Yes, being isolated was not my fear, having little, neither. The only thing I needed was to make art.

MG: What did you find strange in Amsterdam?

AR: Nothing, because I have this very analytical and quiet part in me. I have never been shocked when I was travelling in the west.

MG: What about a visual shock? Moscow was totally different.

AR: Moscow has its own big problem. Russian culture is very intuitive, very emotional, unpredictable and crazy; everything depends on the mood. You cannot make definite plans; this attitude is very poetic but constantly shifting and daily life is very complicated. A part of me is like that. In the west everything appeared to me so understandable and logical. If you apply logic everything makes sense.

MG: Did your relationship to Moscow change?

AR: I go there once per year, I cannot spend more than 10 days there: it is very confusing for me because I’m going to places of my origin like a tourist and stranger. It is a strange feeling to be in a place when you understand the language perfectly but you don’t understand what people are taking about.

I like to discover things that other people don’t see, I like invisible little things, and those things you can find and explore everywhere although there are different accents and different historical patterns. My destiny is to be a permanent stranger.