Adrian Ghenie

Published: April, 2022

Adrian Ghenie belongs to the most brilliant and sought-after artists of his generation. In his studio in Berlin he talks with me about his art, luck and our distorted relationship to art history.

Marta Gnyp: Do you feel at home in Berlin?

Adrian Ghenie: I’m a Romanian living in Berlin. I still think in Romanian – I never learned German.

MG: I think you like to keep a distance.

AG: I do. The idea of integration has been an alien concept to me. Integrate into what? I was never integrated into anything. I have always felt like an outsider. It is a feeling you are born with

MG: Do you also feel like an outsider while in Cluj?

AG: Coming from Berlin makes you different. Being internationally successful isolates you more than anything and more than you want, to the point where it becomes very weird.

MG: Because people treat you like a god?

AG: It activates a whole spectrum of irrational feelings towards you. Jealousy, love, fantasies and conspiracy theories – people are creating a distorted image about you.

MG: Do you try to explain yourself?

AG: After a certain point, I realized that you cannot change anything. No matter how hard you try, it will only add more to irrational explanations. They consider everything but honest, altruistic purposes.

MG: I assume these projections and feelings are not limited to just Romania?

AG: Depending on the group, they will project what they need onto you. I read a random article written by a guy named Kenny Schachter – whom I don’t know – who was reporting about an auction. He mentioned that I was supposedly calling the auction house to say that they put the starting price on a piece too low. There is a moment after a certain level of notoriety when people start to put words in your mouth.

MG: Does this somehow influence your work? Your work shows the dark side of human beings and of the history.

AG: My work is more like a Jungian dream, which is not necessarily bad or good – it simply is. I’m not investigating the dark side of the history. I’m interested in paradoxes within the history that is there. So, I dive into a collective subconsciousness that already exists and is weird and paradoxical, without a clear direction.

ALPINE RETREAT, 2017

MG: So the viewers have to make sense of it themselves.

AG: I found a correlation in my own approach with the method of director David Lynch. When you watch his films for the first time, they are dark and creepy. It is hard to point out exactly what is going on – it’s like a dream. The only thing you know is that you want to watch it, which is more important than clarifying whether it is a good or bad movie. With my paintings, I don’t really care if people give them a verdict of good or bad. For me, it matters that they are interested to look at them

MG: The image never ends in your paintings.

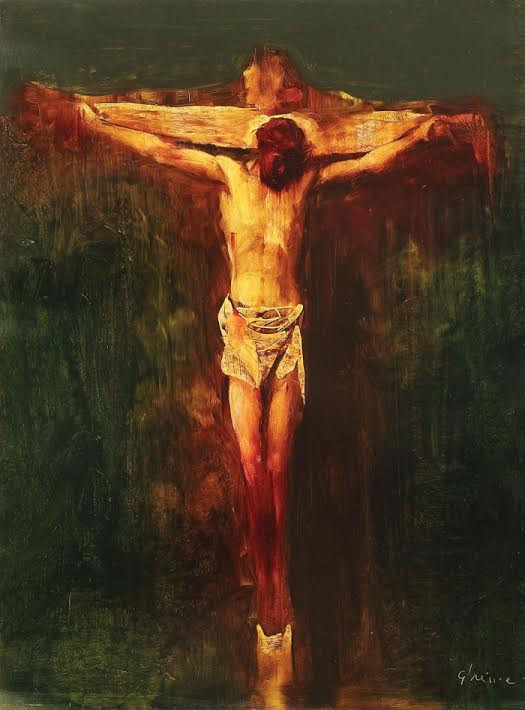

AG: One of the artists I was always inspired by was Titian, during the Renaissance in Venice. He painted semi-transparent layers, one upon the other, so each layer functions as a light box for the next. If you want to have a very special red, you will put a red yellow under it. Or if you want the red to be cold, you would use blue. Imagine how abstract you are required to think! You start a composition that, in the end, has to be a crucifixion, with spots of color that are completely different from the final image. This sense of anticipation fascinates me. You work with this painting in an in-between phase for months, and all the layers are created to get to the final one.

MG: Is this the way in which you paint?

AG: The surface of my paintings is built in layers too but differently, and that creates their richness. I hope that people will respond to that quality, even in an unconscious way. You look at the image first, but the image is not actually relevant. There are thousands of images of crucifixions from Titian’s time, and they are boring. The complexity of the optic juxtaposition of so many layers gives it its quality in the end.

MG: Do you start with a clear image in your head?

AG: Sixty percent of it.

MG: Did you acquire knowledge about Old Masters like Titian at the Academy, or did you discover them on your own?

AG: I applied to art academy in Cluj, but failed. I don’t blame them because I was nothing special at that time, and the academy was sponsored by the state with only 16 places available a year. The competition was vicious. I started to think about how to get there, and asked an academy teacher to coach me, which was common. They would teach you what to do in order to fulfill the academy’s expectations. At the same time at home, however, I did a lot of copies of Rembrandt and Titian, mostly from books. But I also looked at originals in a museum in Sibiu that has a fantastic collection. I read about the technicalities of each period – how to paint on wood and on canvas, how to paint a fresco, and also how to prepare the canvasses.

MG: You were a classical painter when you entered the Academy.

AG: People imagine that an art academy in Romania is very academic. It’s actually to the contrary. My teachers were more abstract painters – figuration was not done.

MG: Because they wanted to escape the politics?

AG: My teachers were of Generation 68, most of whom painted or wanted to paint like the Americans – Rauschenberg or Pollock. The worst thing one could say in this climate was that they wanted to do a copy of Rembrandt, so I kept that to myself.

MG: Did you learn a lot during the copying process?

AG: Copying is an attempt to reconstruct, like what police do when they re-enact a crime. In my case, this period got a special unexpected dimension, which is embarrassing right now. During the 90s, my financial situation was dreadful. I was very poor, so I painted a lot of trashy paintings for people and sometimes for hotel lobbies.

MG: Are they now putting them up at auctions?

AG: Yes. [laughs]

MG: What did you paint?

AG: My mother’s neighbours would ask me to paint a nice landscape, and would give me 50 DM. Back then, I never expected that the Internet would be invented, and all this stuff would appear online. Sometimes I would make a copy of a Pissarro or a Renoir. Most commissions were based on a religious theme, such as Christ or a crucifixion, which I knew exactly how to paint because I had inexhaustible resources for this type of imagery, such as Velazquez. These works are artistically irrelevant to my CV, but at the same time they played a role in my learning process.

CHRIST, 2000

MG: Did you need to make loads of irrelevant art to find your own voice?

AG: There is a funny bias in the thinking of gallerists, curators and critics. They expect you to come out of nowhere and suddenly paint something brilliant. Nobody wants to understand that there is a point in your career where you are making shit. Normally, most of the material from this stage would disappear, but now it all stays online.

MG: How did you experience your Academy time during the 90s?

AG: In the 90s, everybody was poor and everything was cheap. Somehow, we survived with very little. That Pissarro landscape gave me a lot of freedom because with 50 DM, I could go out and have drinks with my friends for many times over a few months.

MG: How did you cope with the absurdities of the system?

AG: There was a factory in Bucharest supplying paint, brushes and stretches for artists, but only to artists’ union stores. I remember, as a 16 year old, going to a store wanting to buy colours to paint. Since I was not a member of the artists’ union, the lady in the shop couldn’t sell me white, black or red – the only color she could give me was violet because nobody wanted violet.

MG: Did you ever convince her to sell you the other colours?

AG: I did. In the end, we became good friends, so she would sell me more material. I never convinced her to sell me white though.

MG: What about brushes?

AG: I shaved my cat to make brushes. We made frames using beams from fences.

MG: What happened when you finished at the Academy and real life began?

AG: I graduated in 2001. At that time, Romania was kind of an outcast from the rest of the world. Only since 2005, the EU has become more relaxed about Romanians traveling to the West. I managed to travel for a short amount of time to the West because my friend’s father sent us invitations and declared to pay the expenses.

MG: Were you fascinated by the West?

AG: Of course.

MG: Is your art infused with history because you witnessed all of these historical transformations?

AG: My family is more to blame. My grandmother was Tatar Russian – a dramatic case. Born in 1911, she lost 11 brothers, as well as her mother and father during the civil war in just one winter. My great-grandfathers were rich shepherds who left Romania in the 19th century, heading to the East looking for large areas to feed their herds of animals. My father was born in 1933 in Crimea. My Russian grandmother, who never really spoke Romanian well, would tell me all the stories. I was fascinated.

MG: Your early works from around 2008 were called Basement Feelings. Was that your feeling of the time?

AG: They were made in relation to my father and the last years of his life. I knew my father as a depressed dentist who was too bored to go to work, and who was sick and tired of his patients. My mother and father gradually began to live separate, parallel lives. He withdrew from all his responsibilities and started collecting junk, rubbish and objects that he placed in his garage and the basement next to it. It was like a jungle.

BASEMENT FEELING, 2004

MG: Did he go mad?

AG: He was kind of a maniac. He had thousands of empty bottles. He drank half of them by himself. Also car wheels, 2 guns that he owned legally because he was a hunter – all kind of objects. He had this idea that one day he would repair all of these things, and we would need them. He slowly created this amazing atmospheric installation. My mother would tell me to go downstairs to get him for lunch, so I would go there and sometimes we would talk a bit, and he would show me something. This environment was unique. Our neighbors had impeccable garages, where they kept their pickles and cars. When my father died, I had to clean the space, which was an incredible journey throughout the family history.

MG: Was it magic?

AG: It was. And it was scary at the same time, because it was so dirty and full of weird objects that you could barely find your way around.

MG: So, your first series of paintings was about going into yourself.

AG: Yes. I was thinking about that space in most of those paintings. The space suggests ‘basement’, so you can see a concrete texture, but then there is always an abandoned piece of furniture with the texture of rotting wood.

MG: Would you consider this series to be the very beginning of what you are doing now?

AG: It happened before. When I left Romania in 2001 after my graduation, I was confused: I didn’t know what to do, so I immigrated to Austria where I decided to quit painting because I had this idea that I didn’t understand anything and that contemporary art was too complicated.

MG: Why?

AG: Maybe I was too much into classical art. I thought that maybe I should have a normal life. In 2001, having a career in art looked simply impossible. I didn’t know where to start. It was like a big mystery to me that completely overwhelmed me.

MG: But you were aware of your skills?

AG: Yes, but I thought maybe those skills could be better pushed in a different direction. I thought that I should restore paintings. I didn’t feel that I knew the codes of the art world, so I quit painting and lived in Vienna like a normal immigrant trying to survive. This ended up being a complete disaster, so I later returned to Romania to live with my mother, which was really depressing. I said to my good friend and then artist Mihai Pop, “I’m not an artist anymore, but art is the only thing I know a bit. Maybe we can do something that is related to art, but doesn’t imply that I have to do it.” So, we opened the gallery PLAN B with a few other friends who shared similar experiences.

MG: Did you enjoy being a gallerist?

AG: After one year, it became extremely stressful to me. I had to deal with artists and I had to deal with collectors, which meant that I had to be social, paying attention to and listening to them. I don’t naturally have these qualities, and it became a burden that was killing me.

MG: When did you start painting again?

AG: I remember it very well. I was in my room. There was a TV on my desk, and my mother was in the other room watching a telenovela. I was bored and had no money – it was February and raining outside. I had a beer with friends the day before, so I couldn’t go there again. I thought to myself, “What the hell should I do with this evening?” Then it crossed my mind: I still have that box filled with colors from the previous years. I saw that the red was still fresh, the blue was fresh, and white as well – and I squeezed them. It took only a few moments to ignite my desire again. For the first time in my life, I had absolutely no ambitions, and I painted without thinking that I would show the results to someone.

MG: what did you paint?

AG: A very small urban scene. I took a few voyeuristic pictures with a cheap camera from my room on the sixth floor of the building. I had this panoramic view of a big courtyard, mostly filled with teenagers in weird, communist architecture at dusk. The couples would hide and kiss. I painted these very humble, naive night scenes. I did four or five of them and then I stopped.

MG: Why?

AG: Because I didn’t have any sort of pressure on me, so it went on and off. After a few months, I showed them to my friends who found them very interesting.

MG: Do you still have these paintings?

AG: No. When I started to have a career, they also entered into the big market machine. [laughs]

MG: Why did this breakthrough happen at that particular moment?

AG: Something that is hard to explain is that the best stuff often comes to you when you’re doing it without ambitions or expectations.

MG: Did this moment make you aware of your freedom?

AG: I became aware of its mechanism. When I looked for a subject, I no longer cared about what other people thought. If you want to be a commercial artist, you never start with a small painting that is 99 % gray and full of shadows. I realized that I could completely ignore what people think, want and say, and just look for something that gives someone the feeling that they are connecting with something inside you.

MG: Like the basements.

AG: I started to think about images that were somehow inside me, and until then I wasn’t aware that they were so important. Don’t go to a library and look at Artforum or a catalogue of god knows who. Just try to remember an image that is specific to you, and live in that thing until you know exactly what the temperature and atmosphere of the image is.

MG. Did people start to appreciate your art all of a sudden?

AG: I don’t think my work would have been noticed if it hadn’t coincided with Europe’s opening up to Eastern countries. I only understood later on that the West had a programmatic interest in the East. I came up with this very specific subject and Eastern European atmosphere that perfectly matched their expectations. They didn’t want a second-hand abstract expressionist piece made by an Eastern European guy – they wanted that basement feeling. For them, that was the feeling of Romania and dictatorship.

MG: You have gradually used more colors came into your work.

AG: At the Art Academy, I painted almost like a fauve – the monochromatic phase of my early paintings after 2006 was very specific for that time, and never happened before or after that that time. When you are confused and you don’t know what to do, you tend to reduce your palette. Think of Picasso’s blue and pink periods. It is a sign of the economy you impose on yourself, which helps you navigate inside yourself. When you do something that is based on your own archive, and investigate what is in your head, you can’t use all the colours – it would be confusing.

MG: Did you paint another series in this limited scale of colours?

AG: I became fascinated by Jungian theories, and was investigating the dream. I tried to remember what the colour of our dreams is, if any.

MG: The international art world noticed you quickly. Did this speedy transition intimidate you?

AG: I don’t want to pretend to be extremely brave, but somehow you play the game and you realize you have to move with it. It’s like when a port opens up, and you have to go through the port because you don’t know when it will be open again.

MG: You grabbed your chance.

AG: I was lucky to get the chance. We will never be able to tell how big the percentage of luck in our success is. One person who played a great role in me being noticed is Jane Neal, a British curator who was interested in Eastern European culture. She’s well connected and associated with the Prague Biennale. I met her at the right time, and the chemistry was right.

PIE FIGHT STUDY, 2012

MG: Coming back to your way of painting: I think that you are one of the few artists who are not afraid to paint lavishly and beautifully. Why is that?

AG: This has to do with the chronological way that the West sees the history of art. Older art is considered a less valuable resource than art that is closer to us in time. For me, chronology doesn’t exist in art. Caravaggio and de Kooning were trying to solve the same problem. Deep inside every painting exists a deep abstract challenge. If you don’t look chronologically at art, every single work of art is a piece of research already done for you – just take it.

MG: Are you not a big fan of the idea of the avant-garde and the modern celebration of progress?

AG: Avant-garde was, for me a liberation and dictatorship in the same time. Modernity created repulsion towards the classical beauty; I don’t have repulsion for that beauty. I had a feeling that modernity was exactly like a Bolshevik revolution: there was a promise, but in the end, they created their own dictatorship. The artistic canon became a new religion. But my fathers are not only Picasso, Malevich or Mondrian, but all artists. Chronology is the disease of the West. Internet and mobile phones have sped this up and made us even more obsessed with chronology.

MG: Why is it so bad?

AG: People are blind to how much they can steal from the past. Most of the artists are stealing from the same pool – 1980 and onwards – constantly remaking and recycling the same thing. This is why painting is a complete disaster today, in my opinion. Old masters are supposed to be in museums in a box, and you are not trained to look at them.

MG: Does the problem have to do with skills? To steal from Velazquez is probably more difficult than to steal from Pollock.

AG: After teaching for three months at an art academy, I concluded that I can teach students to paint in a classical way in just a few months, but that it would take me a lifetime to remove the crap and misguided manipulations that were implanted in their heads at art academies.

MG: What is the crap you are referring to?

AG: The art world today is a gigantic factory of shortcuts. Wherever you go, art students will just look at catalogues and try to steal a formula and reinterpret it – make a shortcut of a shortcut. “Maybe I can fool a gallerist and the gallerist can fool a collector”. At the same time, I’m not suggesting we kill the modernism and go back to Caravaggio.

MG: Instead, you want us to swim in the entire ocean of history of art?

AG: Rethinking the chronological model should come from art theoreticians. The new is not necessarily clean and sustainable. Picasso already showed us how to do it – he was looking back to primitive art, Velazquez, Romanic sculpture, African masks and the Baroque.

MG: What are you looking at?

AG: Everything. I’m stealing from everyone. An incredible place where I can always explore is naïve art. Absolutely everything is a gold mine for me. To imagine that you have to look at ‘quality artists’ to find good ideas is a catastrophe.

MG: How do you search?

AG: You have to have a very cold look, without judgment. There is a nice anecdote about Francis Bacon looking at Rothko. He didn’t look at Rothko in awe – he wanted to figure out whether it would fit as background for his silhouettes. Rothko for him was a background provider.

MG: No hierarchy, no chronology, and a cold eye. What are you working on now?

AG: In the beginning, when people were asking me what I was doing, I was able to offer them, if not an explanation, at least a framework. Now I’ve become so blind towards my subjects that I’m looking for people to explain it to me.

DUCHAMP’S FUNERAL II

MG: You seem to have become fascinated with van Gogh over the last few years. Is this a tribute?

AG: No. It is a very subjective reaction to him. Years ago, when I was in Paris during my first trip in the West, I went to Musée d’Orsay and saw his self-portrait. I was horrified – I found it unbelievably cold. I bought a reproduction of this work and thought about it for a while: why is it so special? I realized that he is not looking out at us, but is looking at himself in a mirror. Most of the time, when you see yourself in a mirror in the morning, it is superficial – you see what you want to see, and you rarely have this cold, lucid eye that, in a glimpse of a second, makes you realize that you saw yourself.

MG: You experienced the painting as cold?

AG: I remember and classify paintings by temperature. Some painters for me are minus 40, like Van Gogh. Rembrandt is on the other side of the scale – the warmest in art history for me. Breughel and most of the Italians from the Renaissance are also very warm. I developed this ability as a kid. I was very small when my mother took me to this museum in Sibiu, I would get closer to paintings that I experienced as warm.

MG: What about the eye of Van Gogh?

AG: That eye for me is one of the coldest places in art history. In most of my Van Gogh heads, the eye is removed and it is a black hole.

MG: Would you like your paintings to be warm or cold?

AG: Impossible to say. It is like not knowing your home’s smell. I cannot judge my paintings in terms of temperature.

MG: Let’s talk about the temperature of the art market.

AG: In the end, it is not so interesting. At the beginning, the financial results were flattering. It would be dishonest to say that I’m not flattered by success. But then I started to feel weird, so it is almost like an anomaly.

MG: Was it influencing your life too much?

AG: The numbers were not in balance. I was too young for those numbers.

MG: They made you serious for a lot of people.

AG: Do you want to be taken so serious at the age of 40? I don’t.

MG: Doesn’t it give you a feeling of independence? You can do whatever you want.

AG: I don’t want to do so much. With most of this money, I finance projects that involve other people. My personal life is a very modest one and that hasn’t changed. Imagine if you gave millions to Giacometti – do you think he would change his studio or habits? Neither would I.

DEGENERATE ART, 2014

MG: Why?

AG: Being a painter implies, without being a burden, a sort austerity that cannot be abandoned or reformed.

MG: You go to clubs.

AG: To preserve my human behavior.

MG: Otherwise you would prefer to stay in the studio?

AG: Painting is a physical process that you have to do with your hands. Your pants are dirty, and you eat with hands covered in paint. Studios are messy and humble environments. If you spend hours in this environment, it keeps you grounded. You cannot do a painting if you are in a clean room, because that kind of cleanliness completely breaks your relationship with materiality. You need to see the materials in their phases when they are accessible and dirty.

MG: In this sense, not a lot has changed if you compare yourself to Rembrandt.

AG: Exactly. The materials that are around you are in a stage of decay, ready to be destroyed. You put a tube of red on a palette, and that is essentially pure red. But in the next second, you mix it with something else, destroying its purity. This is what you do thousands times. It is amazing when you squeeze a full tube of yellow out, and it looks so beautiful and clean. And then the next second, you ruin it.

MG: Is it exciting s to ruin it?

AG: It gives you a feeling of power, and that is the addiction. I act on this purity and change it into something else. You are in charge of the change. This is the moment that makes someone addicted to painting. You cannot be surrounded by money in this case, because that won’t work. Bacon was a millionaire, but he never left his messy studio.

MG: What do you think about painting in our time?

AG: Painting is a time-consuming medium, and is dying out because of this. It is a strange death. More paintings are made and more colours and canvases are bought than ever in history, but the result is very mediocre because it contradicts the speed we live in. Painting is a process based on failure. You learn how to do it by doing it wrong.

MG: Let’s think about something positive for the future: you are supporting a museum in Romania.

AG: It is contemporary art foundation. I bought an historical building in Cluj and consigned it – for free – to the PLAN B Foundation.

MG: What do you want to achieve with the Foundation?

AG: Firstly, it is important to map what has happened in post-war art in Romania. We will do research and publish books. The second task will be to collect and show contemporary Romanian art. Every time I go to Romania, I realize that what has happened there is so interesting. But there are many artists and movements that are completely undocumented. The ideal situation would be that if a visitor came to Cluj in 10 years, they would have an idea what was the Romanian art in the last 50 years after leaving the gallery and the library.

THE COLLECTOR, 2004

MG: Are you giving back to the society as a very successful artist? Or are you genuinely interest in the history and what needs to be done?

AG: Both. It is a kind of detective job. You grow up with the idea that everything was invented in the West and that there was nothing in the place you come from. Then you realize that this is not exactly like that so a lot needs to be done.