Wojciech Fangor

Published: March, 2014, ZOO MAGAZINE #43

The rich artistic oeuvre and the astonishing personal experiences of the Polish artist Wojciech Fangor have been orchestrated by the grand historical shifts of the twentieth century, as much as by his courage to follow his own path.

Marta Gnyp: We cannot discuss your life and art without talking about the turbulent twentieth century. Let’s start from the very beginning: when did you discover that you wanted to be an artist?

Wojciech Fangor: I was already drawing as a child, as all children do. My mother collected my drawings, so I was able to look at them later on as an adult. I discovered that I was already using perspective at the age of three. It was remarkable. My mother told me about a drawing contest for children which was held in Warsaw in the twenties. Since she was convinced that I had great talent she sent my drawings there but they were all rejected as they said a child couldn’t have made them.

MG: Did you later join an art academy?

WF: When I was nine years old I went to France for several months with my mother, who loved art. There I got a box with oil paint, canvasses, and an easel. I loved the smell of the oil paint and I was desperate to paint. After our return, my mother showed my work to Professor Tadeusz Pruszkowski from the Warsaw Academy of Art and he agreed to take me on. It didn’t last long, however, because soon thereafter the Second World War broke out.

MG: What did you do when the war started?

WF: On September 6, 1939 all men able to carry weapons were called to leave Warsaw and sign up for the military service. My father, who couldn’t drive himself, asked me to escape with him. So I drove him to the Rumanian border. Many people were waiting there to watch how the situation would develop, including many members of the government. On September 17, the Soviet Army invaded Poland in the east so we drove even further south, to Bucharest and later to Budapest. There I went to the French consulate and asked them to draft me into an army in France but since I was only sixteen at the time they rejected me as too young for military service. So I went back to Poland.

MG: With your father?

WF: Alone. Actually I ran away from him when he was having dinner with someone. I got on a train and somehow I reached Warsaw and Klarysew, a little village where my mother and sister lived and where I could paint in my studio.

MG: Could you think about painting in such a situation?

WF: Art was extremely important to me, even in this situation. Of course I realized that there was a war. But at first the terror was directed against the Jews. Then, when the underground Polish Home Army initiated attacks on Germans they also started to use brutal violence against Poles. For each German killed they would kill a hundred Poles. But in Klarysew, where I was mostly living, nothing was happening.

MG: Did you continue your art education?

WF: I applied to Pruszkowski to give me private lessons once per week. Pruszkowski was a personality. A France-oriented erudite, he had an excellent knowledge of French literature and encouraged me to read it as well; he played the violin, sang, and was extremely popular with women. He built a castle in the south of Poland, set up the guild of St Lucas for painters, and he was very enthusiastic about me.

MG: Sounds like an inspiring teacher?

WF: It lasted only one and a half years. The Germans were looking to arrest someone who was living in his apartment building. They asked the concierge to give them a list of all the people living in the building who had an academic title such as doctor or professor. Since Pruszkowski was a professor at the Academy he stood on the list. The Germans took them all and shot them dead.

MG: How did you live surrounded by such terror?

WF: I was following all the news, official and illegal, and was waiting for the end of the war. It came in 1944. My young cousin who was a member of the underground Home Army told me that in a few days an uprising would take place. The Germans were already withdrawing; the Russian front was close to Warsaw. I asked my cousin whether they had coordinated the uprising with the Russians. He was upset, saying: “We don’t talk with the Russians.” I told him that I would be leaving Warsaw and asked him to come with me. He refused. I left and he was killed on the first day of the uprising. They jumped with a few revolvers onto the rows of German machine guns.

MG: Where did you go?

WF: To Rabka, a small town in the south of Poland in the beautiful mountains. The Germans were using the pre-war sanatoria as

field hospitals. A few days after my arrival, the Germans surrounded the town and took all men and women to dig ditches against tanks. We were digging ditches from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. After a month my girlfriend and I managed to escape.

MG: Were you aware that the war was coming to its end?

WF: Yes. It was clear that the Germans were leaving, but at the same time the front was still there. I applied for a job at one of the hospitals to have an official document and to become legal. I got the work, disposing the garbage from the hospital, which was not the nicest job you could imagine. Another task was to take off the clothes of the dead soldiers because they buried them naked, all in a wooden case. I don’t know why.

MG: How could you keep on going with this happening?

WF: I was lucky. One day a German officer who was supervising us told me, “I can see that you don’t like what you are doing.” I confirmed. He asked me what my profession was and I told him I was a painter. He said, “We need a painter.” So I got a cellar as a studio and was painting inventory numbers and the name of the hospital on boxes and furniture. I was very happy because I had my own place and moreover it was warm.

MG: Till the Russians arrived?

WF: I was surprised. The Germans had helmets, knapsacks, uniforms, gas masks, and machine guns. You could see that they were soldiers. The Russians were like sparrows. Shabby coats, a piece of rope instead of a belt, bullets in the pockets, simple guns. I thought, whom are the Germans running away from? I was summoned to get to the army but luckily the doctor who was checking me, I don’t know why, exempted me from the front.

MG: You were lucky.

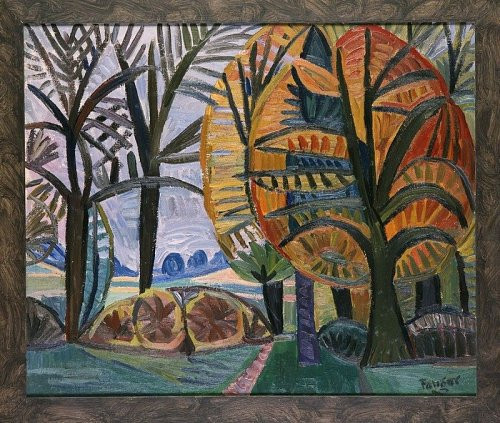

WF: I had a lot of luck during the war. I decided to return to Warsaw, which didn’t exist any longer but Klarysow did. When I arrived there, I earned my living driving people around in a German truck. And I was painting landscapes and portraits. 1948 was a breakthrough year for me. I was educated in the academic tradition. Pruszkowski was fascinated by seventeenth century Dutch painting and Felicjan Kowarski, who became my tutor after the death of Pruszkowski, admired romantic painting, like Delacroix, in combination with the Byzantine tradition. Both of them were very classically-oriented. In 1947 I coincidentally got my hands on a certain book in French. It was the letters of Vincent van Gogh to his brother Theo. I was fascinated. Van Gogh said that museums are worth nothing and that an artist needs to work with what is today. Neither Pruszkowki nor Kowarski mentioned van Gogh or any other avant-garde artists, sporadically impressionists. Van Gogh wrote so suggestively about his experiences and thoughts that I got on my bicycle and went to paint en plein air and in my way. He woke me up. I made maybe a hundred paintings at that time. It was a very important moment.

MG: Because you left academia behind you?

WF: Yes. I already possessed the technical skills, including drawing, but it was about a different approach to the role of color and form. If was not about the representation of reality but an interpretation of reality, and shifting reality into the construction of images. A painting is something other than the appearance of reality, although there are connections between them.

MG: Van Gogh helped you to discover yourself?

WF: Yes. More through his words than his paintings, though. When I look at reproductions of works by someone else I always have the feeling: this is not mine. But I can identify with someone else’s emotions through words.

MG: It was also a time of political change in Poland.

WF: Because of the war, the German terror, and the Russian victory I started to read newspapers and journals and got involved in the discussions about art and Marxism. I bought myself Marx’s Capital and The History of the Russian Revolution. I read The Communist Manifesto, which is very poetic and suggestive. I became an enthusiast, privately, because I was living in a village. Later I took to visiting Warsaw. The Café Lajkonik became a meeting place for artists, architects, and journalists. There I met people like Henryk Tomaszewski, who later became one of the most important graphic artists of Poland, and the architects Zamecznik. I got in contact to my social artistic field.

MG: Did they accept what you did artistically?

WF: My modernistic paintings were problematic. My landscapes, my portraits of Chopin or even of Lenin were not understood. In 1948 I had an exhibition in the Club of Young Artists and Scientists but I didn’t get much positive response. What made the situation even more complicated than my artistic approach was the problem with my father.

MG: What happened to your father?

WF: He got arrested in 1948. Before the war my father was a wealthy industrialist. After the war, the young socialistic regime had allowed private initiatives if the number of employees was to be limited to fifty people. My father set up a company that traded in scrap nonferrous metals. He collected and sent it to a foundry for melting. Sometimes, however, there were also half-products between the scrap and he sold them to other factories. He was getting more money, but on the other hand the factories were getting products, which they needed and he saved these products from being used wrongly. He was denounced and accused of economic sabotage and causing losses to the state. The state organized a show trial in Katowice, which 5,000 workers were forced to attend. The military tribunal sentenced him to death.

MG: A nightmare.

WF: Neither my father nor me treated this seriously at first. It was a show trial to intimidate the bourgeoisie. But they put him in the death cell. My mother found a famous lawyer whose friend was the chief of the presidential office. He simply placed a document in which the death penalty was changed to a life sentence between other documents that the president, Bierut at that time, signed.

MG: A life sentence in a Polish jail at that time doesn’t sound very promising either.

WF: At least he was alive. He was in jail and I was making a socialist career. I painted a work that became very popular: Korean Mother.

MG: Were you truly ideologically motivated when you painted it?

WF: Totally. At that time the anti-war propaganda was very strong. Many believed that America wanted a war with the Soviet Union. When the Korean War started the danger that the Cold War would become hot was real. I wanted peace, so I wanted to contribute to this process.

MG: Didn’t you have an inner conflict having a socialist career while your father was so badly treated by the same system?

WF: This was very complicated because I was always fighting with my father. I didn’t like him. I felt uneasy in his presence. He was an outstanding businessman and saw me as his heir. He expected me to be good at school, especially with regard to economics and bookkeeping. But I didn’t have any predisposition for it, nor did I like it. To my father being a painter was like being an alcoholic. But our conflict started much earlier. He was the son of an officer; he was an officer himself and raised his children in a militaristic way. So when he was put in jail I had mixed feelings: on the one hand I was happy that I was no longer exposed to him, on the other I was fully aware of the injustice done to him.

MG: How did you cope with this situation?

WF: When I became a well-known social-realist artist I got acquainted with the Vice Minister of Culture who liked to spend his time with artists. He was friendly with Prime Minister Cyrankiewicz. Through him I got to see Cyrankiewicz and asked him to set my father free. One week later they opened the door of the cell and let him go on convalescent leave.

MG: Was your father grateful to you?

WF: He had changed and become softer. It was only after his time in jail that we started to address each other informally. He still had a lot of energy and wanted to work but he didn’t have any civil rights. In 1958 he asked for a revision of the sentence of 1948, when the political thaw made it possible. The High Court changed the sabotage accusation into a criminal case because it gave him his civil rights back but the state didn’t need to return the confiscated assets and land. Later, when Poland became a democratic country, this revision was precisely the reason why my family couldn’t get anything back. The sabotage against the state was seen as a communist affair, which could be undone but a criminal case could not.

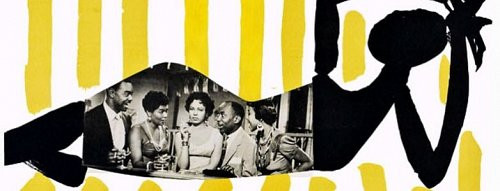

MG: At that time you also got involved in making posters.

WF: I started to make posters because I needed money. Nobody was buying paintings. Sometimes the Ministry did but not on a regular basis. I worked as a lecturer at the Art Academy for an income and insurance, so I could use the poster work to make some extra money.

MG: The Polish Poster School has become a name in the world. How did it start?

WF: The idea came from the director of film propaganda at the Center of Film Distribution. She was importing films from the whole world. There was no need whatsoever to advertise for these films since there were only ten cinemas in Warsaw and there were always long queues to get there. Still, she invited a few artists such as Henryk Tomaszewski and myself to help her design posters and to choose other artists. I have never studied graphics but thanks to modernist techniques I knew I could do it.

MG: You lived outside Poland for a long time.

WF: The first time I traveled abroad was in 1956 when my father left jail. Only then was I allowed to move from Poland. I went to Brussels when an exhibition of young Polish art was organized. We were discovered during the Youth Festival in 1955 when left-wing youth came to Warsaw en masse from the whole world. I also had a sister in Vienna who had married an Austrian before the war. She was able to arrange an invitation to Austria and to guarantee financial security for me there, which was necessary to get a passport and $5 for travel. I was investigating the possibility of staying there but I came back.

MG: You wanted to emigrate because of the political system?

WF: Yes. From 1954 onwards I knew that the system was a utopia, a beautiful ideology, which produced the opposite in reality. The economic situation was absurd. I wanted to leave for the USA, which had always attracted me. Immediately after the war I visited the American embassy in Warsaw and asked for emigration documents. I heard that there was a waiting list — there was a quota for 6,000 Poles per year — and that if I apply they would be able to react to my request in ten years.

MG: Did you have contact with foreign artists or institutions?

WF: In 1958 I exhibited my paintings in a show called The Study of Space, which was the world’s first environment. After this exhibition the director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, Willem Sandberg, came to visit me and invited me to make a similar work in Amsterdam. The gallery owner Beatrice Perry from Washington came and was thrilled by my abstract works and wanted me to show them in the USA.

MG: When did you start to make abstractions?

WF: In 1957. Nobody understood nor liked my abstractions; the majority of the Academy didn’t consider it to be art.

MG: Where did your ideas on abstraction originate from?

WF: Firstly, there was a universal crisis of figuration. This was in the air everywhere in the world. Secondly, I was personally connected to architects. Even in my realism there was always a solid construction and the architects could sense it. If they wanted to work with an artist they thought of me. I did some project with the architect Jerzy Soltan. With Stanislaw Zamecznik I discussed space. They thought that I had a spatial intuition, which is not functional.

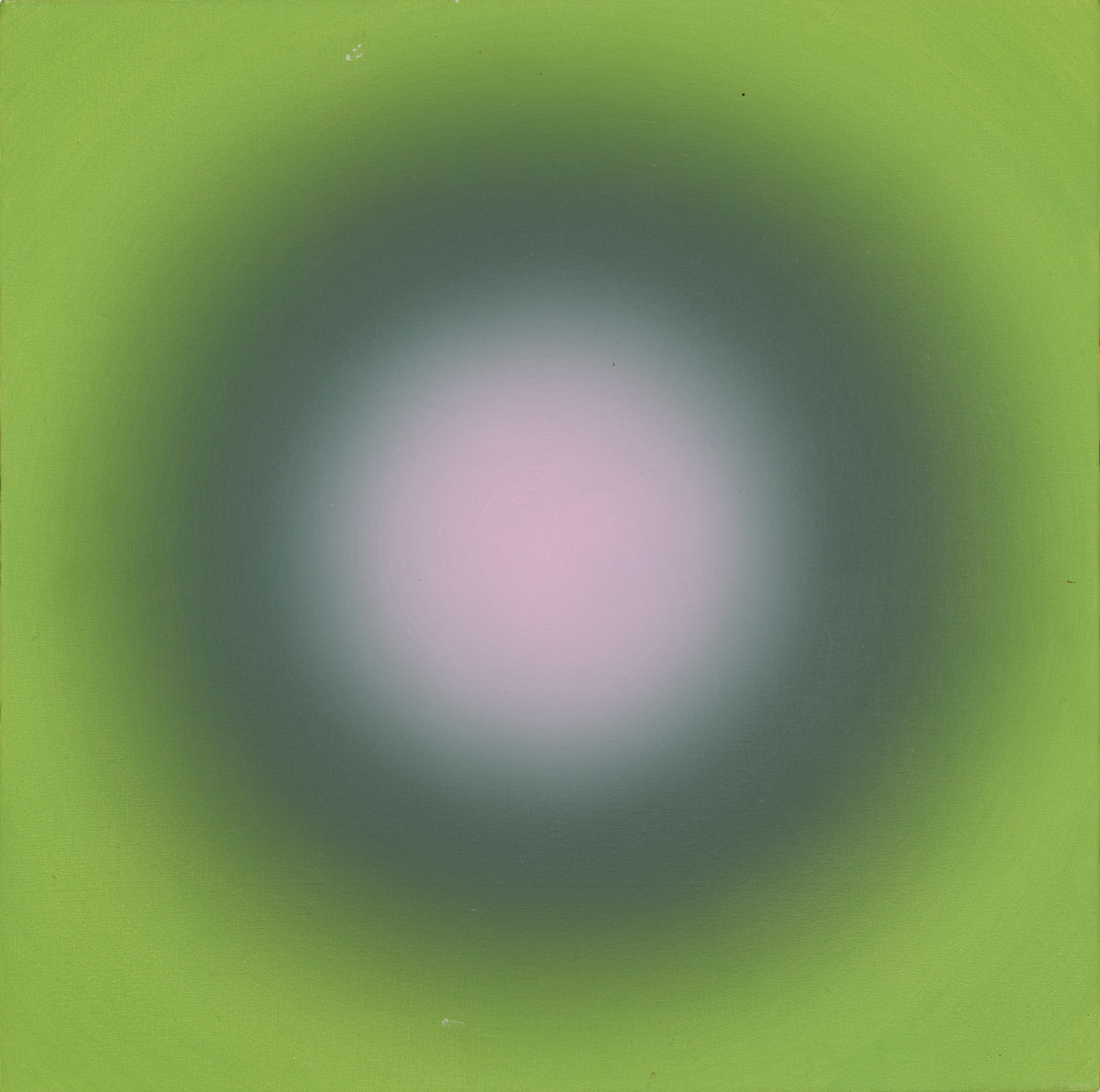

MG: How did you treat space then?

WF: Space as a material to construct independent art and not only as a material to build functional architecture. Three-dimensional space as a material to express emotions and a worldview just like the paint on a two-dimensional surface does. Later I discovered that my paintings with diffused edges of color and shape create a spatial illusion, which is not directed to the inside of the surface (like perspective), but extends in the opposite direction toward the outside of the surface into the real space between the painter and the viewer. A new kind of spatial illusion. This discovery might have originated from my interest

in astronomy and my fascination with optical instruments, with the effects of shifting the image in or out of focus. But it took some time to find the rational theory of this phenomenon. All important discoveries originate from unconscious intuition.

MG: Did you have contact with abstract expressionists in the USA?

WF: None. The first time I saw a Rothko was in 1962. I was surprised that he was painting in such a similar way. I liked him very much. At that time there were two camps: abstract expressionists and Pop Art. I had contact with Anuszkiewicz, Richard Artschwager, Stanczak. Josef Albers visited my show in 1967 at Chalette Gallery in New York and said, “chapeau bas!” He was very positive about me. He invited me to his house in New England. As rational and constructed as he was in his paintings as childish he was in his life. He pointed to the blue sky and clouds and said to me: “They have the same value but differ in color, the same as in my paintings.” He was maybe forty years older than me but treated me as an equal.

MG: Was it relevant for the Americans that you were a Polish artist?

WF: Sure. In 1956 Poland was very popular in the USA because Americans treat culture in a political way. If something happens somewhere that they consider politically correct, they tend to reward the culture of this country. Thanks to the anti-communist movement in Poland in 1956, Polish art got a chance in the USA.

MG: How did you like living in America?

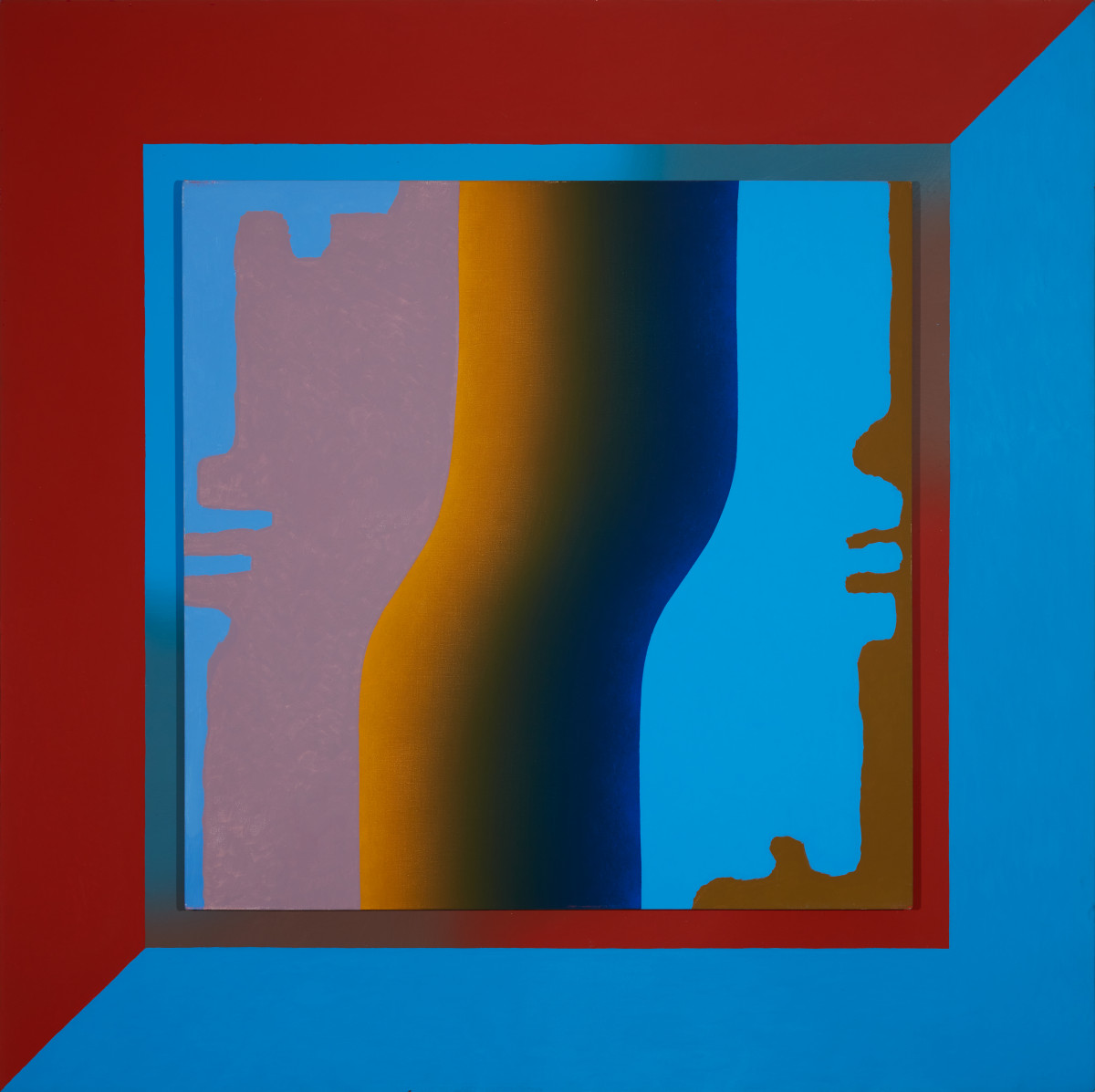

WF: It depends. I got a job as professor in the art department at the Fairleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey about fifty kilometers north of Manhattan. Very well kept buildings, beautiful parks, I found myself a great studio situated in the attic of what used to be a theater in the nineteenth century. I hired students to help me and employed them in the carpentry workshop. I worked with large canvasses. I painted many circles and waves at the time.

MG: Did you have collectors who were buying your works?

WF: Gallery Chalette in New York represented me. The gallery was set up by the Polish biochemist Lejwa, who was caught in the USA when the war broke out in Poland and stayed. Together with his wife, who had the ambition and looks of Helena Rubinstein, they started the gallery that represented artists such as Viktor Vassarely. I visited the gallery for the first time in 1962 and showed Lejwa a few photos of my work. We had lunch together but Lejwa told me, “What you make is unsellable.” Three years later, the son of Vassarely Yvaral, who saw my work during a symposium at the university, brought him to me. Lejwa saw my abstract circles, took my hand, and asked me to immediately join his gallery.

MG: Were you happy with the gallery?

WF: He was selling a lot. The price was about $1,500 per work, of which I was getting half. I could live well thanks to my art; he may have sold more than a hundred artworks in the period between 1966 and 1973. He also helped organize my solo show at the Guggenheim Museum in 1970. It still makes a big impression in Poland because I am the only Polish artist so far to have a solo exhibition there. For the American public the exhibition was too late to generate enough attention. Op Art was en vogue in 1965, not in 1970.

MG: You mean that the exhibition went unnoticed?

WF: Before the exhibition started, I got a big article in The New York Times. The important art critic Canaday wrote an enthusiastic article about my art, although I think that it was more a part of the conflict between Op Art and Abstract Expressionism as proposed by the art critic Greenberg.

MG: Did you ever meet Greenberg?

WF: In 1962, during a private dinner. Greenberg said, “It is interesting what you are doing, it connects with our young American painting school, but you should paint on raw canvasses. A painting is not a lollypop.” I tried to explain my idea about space to him but he was totally uninterested. Canaday found Greenberg very dogmatic and to provoke him he wrote a whole page about me, and my great art.

MG: Why did you finally decide to go back to Poland?

WF: A French communist who dreamed about living in the USSR emigrated there but came back to Paris within a month. His French comrades asked him, “Why did you return?” He answered, “Because they let me out.” I decided to go back because Poland let me in.

MG: America wasn’t the country you dreamed of?

WF: In the ‘80s my artistic career had come to an end. I went on pension from the university by the way, I have never enjoyed teaching. You cannot teach art, you can only teach technical skills. There are very good art teachers, but they are not good artists — if you give too much of yourself to students you create by teaching. I have never liked schools, never attended an art academy; never liked to be a part of an organization. Even when I was fascinated with Marxism, I was never a party member. I moved 150 kilometers north into a beautiful small village with a great view over the mountains, sixty hectares of land with wonderful lakes. In winter the snow was sometimes three meters high and the temperature minus thirty degrees Celsius. I had to clear the snow myself and at a certain point in time it became too much. I decided to move to a better place and chose Santa Fe in New Mexico, 300 sunny days a year. My wife and I loaded a big truck, and together with our four cats we moved southward.

MG: And did you find what you were looking for?

WF: The nature was amazing, the architecture beautiful: a combination between Spain, the Baroque, and Indians. I found a very good house to work in. But it was a cultural desert. Or, if it had at least been a desert it would have been better; it was a pseudo-culture for tourists. Fake Indian artifacts. I was painting landscapes, still lifes, and my surroundings, but nobody was interested in what I was doing. When democracy came about in Poland the return became an option.

MG: Had you stayed in touch with the Polish art scene?

WF: Some people visited me. I thought that if I could buy an old monument and reconstruct it, make a studio there, then I could live in Poland. And indeed I made a career in Poland at the end of my life. There has been a lot of interest in my work.

MG: How do you explain this huge interest?

WF: People understood that art could be a good investment. Some five rich collectors bought my works and sold to another fi ve rich people and doubled their investment. Obviously, I’m not getting anything from the price increase.

MG: I can imagine that it gives you a good feeling that your works have become worth a lot.

WF: Pity that this came when I was ninety and not when I was forty. I was also thinking about a private museum but because of the nonchalance of Polish institutions this idea didn’t materialize. I did get a very good retrospective in the National Museum in Krakow and Warsaw.

MG: Do you enjoy your position now?

WF: I still paint. I need to sit, however, because my spine doesn’t work. I paint what I like to paint. Maybe later my current ideas will get a cultural or formal meaning.