Edward Lipski

Published: March, 2015, ZOO MAGAZINE #46

In the cultural surrealism of the British artist Edward Lipski there is no place for linguistic games and institutional vocabulary. Analyzing the human being using discomfort, spirituality and rituals Lipski aims at expressing the essential.

Edward Lipski: I live and work in my studio because I work at random hours during the day and at night. It also helps me not to separate my work from what I’m thinking and doing. One moment I’m playing the piano, the next I’m making a work.

Marta Gnyp: The romantic notion of the artist who doesn’t make a distinction between work and private life?

EL: I think this is the only way. The work has to be about your reality, if it isn’t it’s not worth doing it. This is my belief in a very abstract sense; my work is about making a reality.

MG: You graduated from art school in 1993 at a time when the young London art scene was very much determined by YBA. Your work seemed to be different though; you didn’t apply sensational “killer ideas” as they did.

EL: They were ironically related to the world. I wasn’t. This was the era that people made work that was supposedly shocking and transgressive. Some of my works were to some extent about transgression – although this is a vague word – but I didn’t come to that through public shocking. It was more a process of self-discovery.

MG: Why do you use sculpture as your main medium?

EL: I make three-dimensional work, which is not about depicting imaginary spaces but it is always about the reality without an illusion.

MG: In this reality you give life to the objects?

EL Absolutely. I like this ancient metaphor, which we are by the way no longer allowed to use. The current institutional language is so strictly self-referential and therefore for me very limiting. A friend of mine was speaking about the in-between space. He was confused when I asked him whether he could find a name for it, which feels right for that sensation. We have removed certain words from our interaction with the world but we feel uncomfortable because we can’t use these words anymore. We have no replacement in the constructed universe we live in. That’s why I enjoy dead words like spirit, god, and soul.

MG: How do you make your objects?

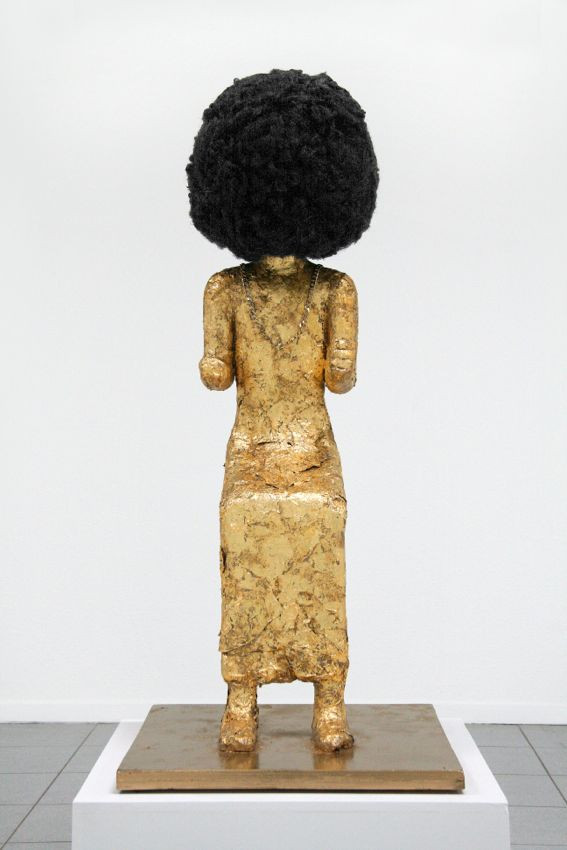

EL: In my work I often use historical objects that retain ideas of spirituality. I also use the iconography that these objects represent. But I destroy the expectations that you might have for the use of objects, which suggest that they were religiously utilized. For example, I’ve used Chinese

sculptures as they are used in Chinese restaurants, displaced but familiar.

MG: Do you often use found objects?

EL: Some African sculptures were found, others I made myself. I found them here, in my own culture, not in exotic places. They were meant for worshipping in their cultural setting but when I bought them they were already disrespected in this function. It is not that I’m reinforcing a traditional institutional version of them but I’m animating them. I have an outsider art approach reality.

MG: Why are you looking for objects that retain certain spiritual or ritualistic values?

EL: The functional use of spirituality gives it a resonance. For example, icing is used for making celebration cakes, and therefore is a visual celebration of something you are going to eat. When I used icing together with the African Fang sculpture it is like a sampling of two cultures to create a new thing. It is cultural surrealism, rather than surrealism based on two objects from the same culture. I find that relationship interesting. Simultaneously, in a bigger picture, I do think that metaphysics has been denied as a means of interaction.

MG: Do you think that metaphysics belongs to art?

EL: As much as much holding a piece of art in your hands belongs to art. You need many vehicles and experiences to interact with the world. If you deny a vehicle of interaction you will not be able to feel the potential experience in something. Holding something, touching, feeling in various ways can open up different relationships.

MG: What kind of connection between the object and the subject do you mean?

EL: A primordial instinctive relationship, which is somehow completely out of fashion also because of linguistics. I take the outsider perspective; it was never my concern to align myself with the current art language. I look to the streets, I look at my environment; that’s where my art culture is being formed. It has to have a relationship to my life in its roughness.

MG: Let’s talk about the spirit of the time, which is another concept that is considered to be worn-out. I had the impression that you were often ahead of your time with your formal language. I saw your sculptures from 2008 and though this is the same primitivism that some young artists are using now.

EL: I look to the peoples of the world, rather than in the art world. I look at raw nature. I listen to a lot of contemporary music to get sense of what time I am in because music is faster than art in the sense of connecting with the times.

MG: What would you call the quintessence of the now, which you also try to put into your works?

EL: A combination of vagueness and particularity. Enjoyment and pleasure that comes out of interfacing things that are disparate in sensation: very technological and very rudimentary, very rough and very sophisticated. There is always a problem in the language when translating processes of visual language into verbal.

MG: We have no other option but to translate it.

EL: I agree. I use a lot of different words to describe what I’m doing because this is the only way of connecting so that it becomes a linguistic game. YBA language was far more consciously aware of itself and what it was trying to achieve. Mine is much softer. It is about the interaction between things; you can read it on different levels because each thing has a quality related to other elements. I’m looking into something that in a way is related to an ancient, primordial experience. The hardest thing is to give it linguistic form.

MG: Did you find one?

EL: That’s what philosophers are trying to work out. I have never met anyone who could give me a simple explanation. I found poetry of much more use than philosophy, because the latter tends to go in circles and the only thing that gets invented is terminology. My era of submitting to terminology is over. What I want now is a resonance in my head, which can come from very simple statements.

MG: Could you give me an example of such a simple statement?

EL: A religious person once told me: “God gives you more that you could imagine.” That sounds incredibly simple and beautiful. Imagination has a limit; a “more” is more than the limit. A simple poetic sentence.

MG: Are you yourself a religious person?

EL: No. Religion is a means of human beings to understand themselves within a system so you can put anything into this box. We still live in a religious culture; we just replaced the religious with new terminologies. I’m a heretic because I don’t trust any institutional framework. I don’t trust the institutionalized vocabulary. Currently the idea of self has become a new religion. This is why people are doing much more research into the inner world, which is why we go through psychoanalyses.

MG: Did you experience psychoanalyses yourself?

EL: A lot, including group therapies. It was just to explore this territory. I was a heretic also in that environment.

MG: Why are you so against institutions?

EL: I think they are limited because every framework has a goal. Still, I enjoyed being part of education, therapy, and many other frameworks.

MG: Have you ever had an experience of the self that radically changed something in your life?

EL: I was in Peru four years ago, in the jungle doing Ayahuasca – it was a profound experience that fundamentally affected my relationship to the world.

MG: Is art an instrument to channel your experiences or is it a goal in itself that uses experiences.

EL: Art is a form of communication. I don’t know why one would need to create this divide. The self, experience, the art, and the art world – I don’t think these things are so separate. I put them in one ball. Pretending that there is a difference, which the academic approach does is madness.

MG: Is this not a matter of which angle of perception you choose?

EL: If you want to perceive art as a social and political act then this is a conscious perception of something that you want to control and you use theory to understand it. I don’t see it as being so directional. For me to be able to have this power to control something is an illusion. I’m participating in art culture. I’m not searching for that elemental person called me. I’m not searching for the elemental code called art.

MG: We can’t speak without categorizing.

EL: Maybe my categories are different and I don’t have hierarchical beliefs. I might go to a museum and like a particular work – everybody will agree that this is an important work but I might disagree with the work next to it. I just trust my eye. Shopping infrastructure is very similar trying to make you believe that you are a part of something that is valuable.

MG: Why don’t you connect with other artists?

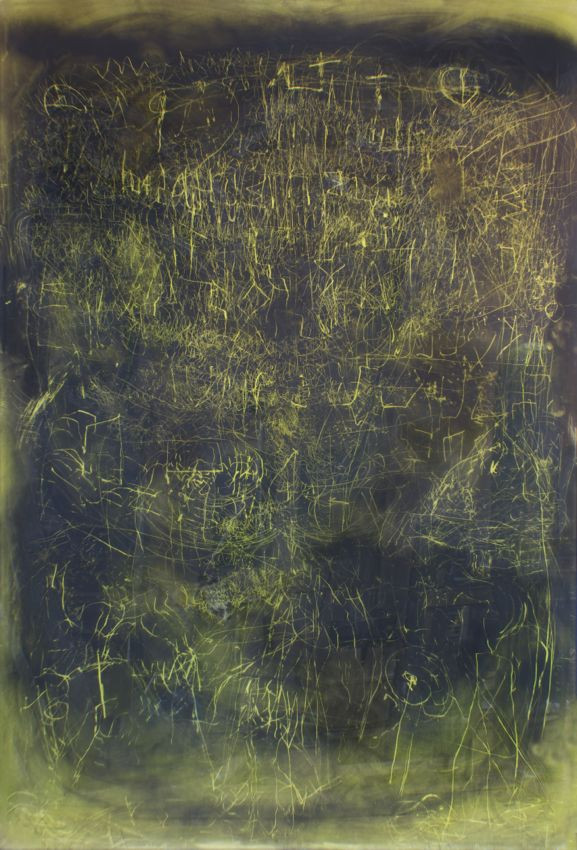

EL: Maybe because I work across time, before and after my time. Right now I’m using the terminology “mystical vandalism.” I’m moving away from cultural terminology now because I think that there is something else more interesting.

MG: How long does it take you to make a work?

EL: About a month, but then I’m making about four works at the same time. I work it over and over and keep it around for quite some time, perhaps destroy and remake it.

MG: Your name is Polish.

EL: My father was born in the Ukraine but he considers himself Polish. I recently went to the Ukrainian village where he was born. He has a very complex history and had a very hard life through the Second World War and the Russian Gulag. My mother was from Paraguay.

MG: What’s your first language?

EL: I was raised listening to Polish, English, Spanish, and Guaraní, which is the indigenous language of Paraguay. My grandparents spoke Ukrainian. There you see the blueprint of my need to deal with layers of culture.

MG: The Paraguayan and Polish cultures are both very spiritual.

EL: My father is totally uninterested in religion. He also sees it as source of corruption. My grandmother, though, was holding the bible all the time. My mother was more the product of syncretism; she kept a lot of pictures of saints, as is the tradition in South America, where they have a tribal approach to Christianity. I went to a Catholic school.

MG: Your parents brought you into interlacing cultural references.

EL: We had a lot of friends from different cultures and there was a constant movement of different influences. My use of Chinese and African objects could be seen as a metaphorical approach because the two continents never had a historical link.

MG: Do you consider your work as a form of a global language?

EL: Depending on which kind of globe you sit in. Even being in one country doesn’t mean that you share the same sensibility. The countryside offers a totally different experience of the world than the urban context does. I would speak about the city instead of the globe.

MG: Ideas of globalization sometimes produce a kind of belief in a togetherness and bright future.

EL: I’d rather deal with the reality than the fantasy. I look for discomfort. In my work I am interested in the idea of what tradition means in opposition to contemporary culture. I take it on board as another avenue. What happened in the Ukraine is not only the division of the country but about the culture, traditionalism versus the liberalization of culture.

MG: Do you attempt to show people how culture functions?

EL: Controversial opinions are very discomforting for some people, especially two subjects: religion and culture on its peripheries. I talk regularly about it because it doesn’t scare me. I speak with people who are religious and I’m not religious and I talk to people who have ideas about culture that are different from mine. I’m interested in zones that are outsides mainstream thinking.

MG: What about the meaning of your work: do you try to impose a reading of it on the viewer?

EL: I don’t think that artists have a choice in the architecture of culture they live in. You are going to be assimilated in the system. You are not able to dictate the meaning of understating; it is beyond everyone. We don’t have a singularity to use as a model so we cannot have an authority, although certain institutions are claiming it.

MG: Does the reception of your work interest you?

EL: I want an experience from the viewer. It can be anybody, from the cleaner to an important collector. I trust the work over a duration of time. It is not about the necessity of it being experienced now, maybe it’s five years or one year from now. It’s about the interaction between a human being and something else. It can happen randomly.

MG: Do you collect objects yourself?

EL: I don’t have things that are valuable around me apart from being alive. Nothing else. I know I can lose it so there is no point in holding on to it. I’m not interested in things but in experiences; things stimulate experiences though.

MG: Are you also interested in magic?

EL: Very much so. A visit to a gallery is a kind of theatrical and magical experience, the way in which something becomes an experience called art. From the opening of the door, through the concept of the white cube, the entire reception of art is ritualistic. I’m inspired by ritualistic cultures in general. Religion is so interesting and relevant because it embodies more rituals than other phenomena. It is also constructed in terms of rarefication of materials. I like African voodoo, Hindu and early Catholic tradition because they use material to translate a symbolic relationship into reality. Also, the interest in money can be seen within this perspective.

MG: As a form of a ritual?

EL: Once you remove religion and tradition as tools, you need to replace them with something else and that’s money. You can mess up your entire life being an artist, so it is not something you choose to do without the intention to get in deep. And that’s what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to make good art and the rest of the infrastructure is secondary, even though I’m aware of it.