Miraculous Resurrections: the contemporary art market of older and deceased women artists

Published: April, 2017, LECTURE AT THE ANNUAL ART HISTORIAN CONFERENCE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF LOUGHBOROUGH

During the Venice Biennale 2015, out of curiosity I went to see the Azerbaijan Pavilion. The exhibition turned out to have been curated by the British curator trio Artwise who included works by several international artists, one of which I found striking. It was a large, colorful painting with the title sentence written in childlike writing. The text was over-painted, as if corrected, propped in between naively painted birds, a crocodile, and a lion. Minimum means and maximum effect: you could see the unprimed canvas, dirt on a few spots, scarcely used paint, the narrative if any, complicated by the clearly visible construction of the painting. It was a highly energetic work: not only hilariously mocking our good human intentions, but also playing with everything we know about good and bad painting. I fell in love with this work and discovered Rose Wylie. To my big surprise, Wylie turned out to be an eighty-one-year-old woman. I immediately got the full story from the curator: Wylie was said to be the art darling of Nicolas Serota who had apparently started writing letters to her recently and paying visits to her little country house outside London; Wylie was “discovered” in 2010 after her participation in the exhibition Women to Watch at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington DC when the writer Germaine Greer declared Wylie the hottest artist of the Brittain in an article in the Guardian. The curator told me that Nicolas Serota had already bought a painting for the Tate. It took the world however a few more years to get to know the artist better. In the meantime, Wylie had several institutional and gallery shows in different parts of the world, including at Douglas Hyde in Dublin, Städtische Galerie in Wolfsburg, Turner Contemporary in Margate, Chapter in Cardiff, and Space K in Seoul. She won the John Moores Painting Prize in 2014, the Prize of the Royal Academy in 2015 and in the same year she was also elected a Senior Royal Academician. The demand for her works from collectors has been rapidly growing. Her last gallery exhibition was at one of the most powerful galleries in the world, David Zwirner in London, which might represent her in the future. All the artworks were sold out on opening night.

The story of Rose Wylie starts in the 1950s. She attended the Dover School of Art, where she met Roy Oxlade, whom she married, and stopped painting to take care of their three children, one of whom required a lot of attention. Oxlade carried on painting while Wylie dedicated her life to their family. Interestingly enough, despite their bohemian and unorthodox lifestyle, they assumed traditional gender roles when it came to this. It was only after their children had left home that Wylie took up art again, completing her studies at the Royal College of Art in London in 1981 and embarking on her artistic career: although “career” is not the right word to use. As a woman in her fifties she was not really welcomed into the art market, to put it mildly. Wylie continued painting, though: big canvasses, the scale limited only by the size of her studio at home in Kent, engaging with stories taken from mass media, fascinated by celebrities, and observing nature. She has developed her own language of signs and marks, a sparse use of paint and brush (sometimes working with her hands), which was also forced upon her by her limited financial situation. She was noticed here and there, invited once by Neo Rauch to participate in a group show that brought her a gallery, Union, but not a lot happened, really, until 2010. Rose is a phenomenon, but not an exception. As I will show you, we can speak about a category of older or dead women artists who have recently been warmly embraced by the contemporary art market. In the last six years, we have seen a surge of older or dead women artists joining important galleries and being shown at important institutions. A few examples are: Mira Schendel (1919–1988) represented by Hauser & Wirth since 2014, Carmen Herrera (born 1915) with Lisson 102 since 2012, Phyllida Barlow (born 1944) with Hauser & Wirth since 2010, Senga Nengudi (born 1943) with Dominique Levy since 2015 (now Levy Gorvy), Dora Maurer (born 1943) showed by White Cube in 2016, Alina Szapocznikow (1926–1973) with Andrea Rosen since 2015, Geta Bratescu (born 1926) with Gallerie Barbara Weiss since 2013, Joan Semmel (born 1932) with Alexander Gray Associates since 2011, Betty Woodman (born 1930) with Isabella Bortolozzi since 2013, Pat Steir (born 1940) with Dominique Levy since 2016, Etel Adnan (born 1925) with Gallerie Sfeir-Saimler since 2010, with Continua since 2013, and with White Cube and Galerie Lelong since 2014, Inge Mahn (born 1943) with Max Hetzler since 2015 and Ruth Asawa (1926–2016) with David Zwirner since 2017. The list is much longer and will probably be growing. Why?

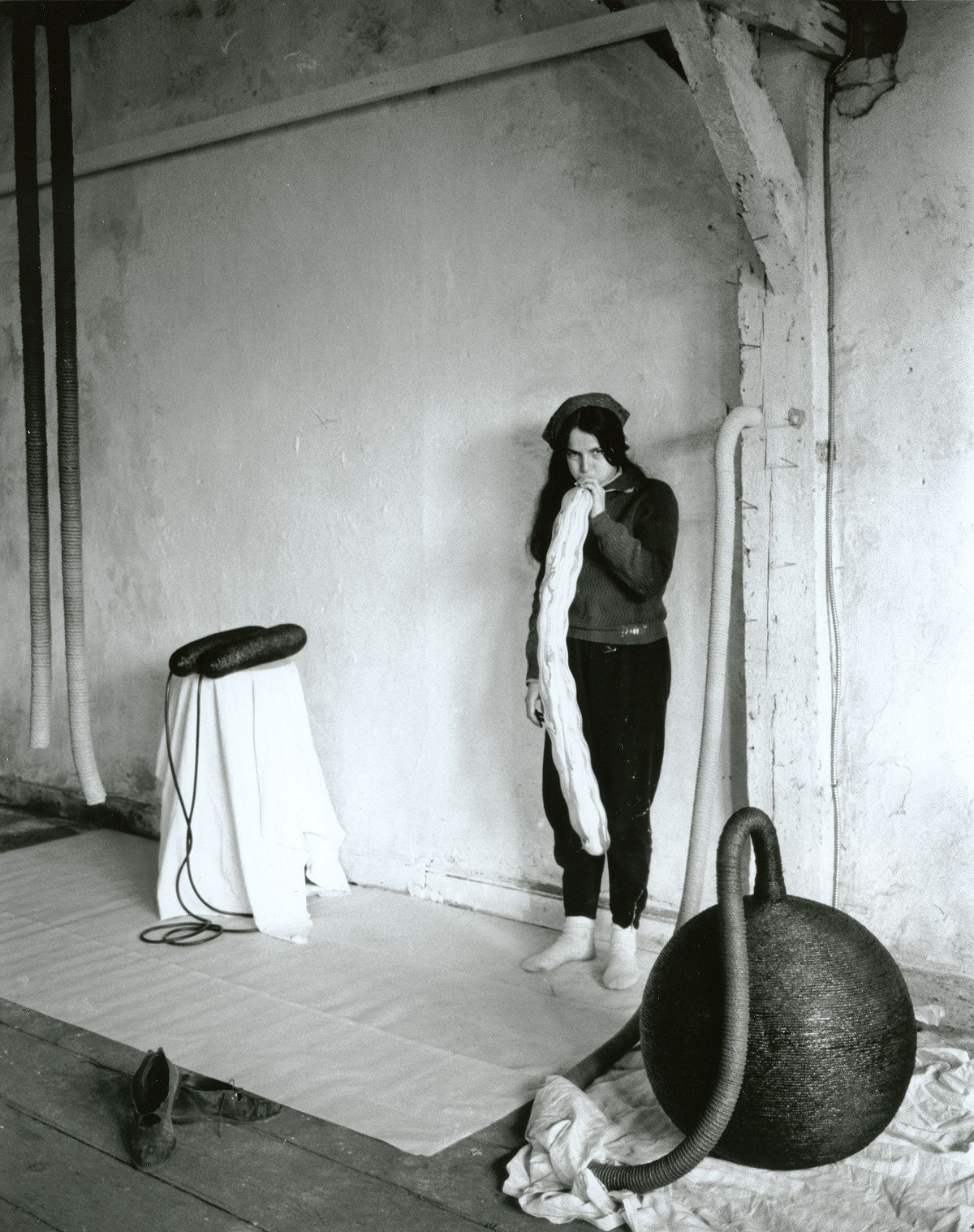

Let me explain this sudden interest using the example of British artist Phyllida Barlow who has been engaged in redefining the medium of sculpture since the 1960s. She graduated in 1966 from the Slade School of Fine Arts in London and, since she could not earn a living from her artistic work, she worked as a teacher at art institutions and continued doing artistic work in her spare time. She was raising her five children and, according to the artist herself, she had so little money that she was forced to recycle the materials she used for her works, so there is hardly any sculptural work by her from the period before 2010. Her works often interact with the space; they look raw, unfinished or quickly made, as if the traces of the creative process are still palpable. Barlow has always used cheap materials, such as packing materials, cement, plaster, textiles, polystyrene, and paint.

Her breakthrough came in 2010 when the gallery Hauser & Wirth included Barlow in their stable of artists, and, from that moment onward, at the age of sixty-six, her career accelerated. All of a sudden, the artist was invited to produce solo exhibitions at the Henry Moore Foundation in Leeds, she got the Aachen Art Prize in 2012, the solo show Siege, at the New Museum in New York (2012); she was invited for the Kiev Biennale and the exhibition Before the Law, organized by the museum director Kasper König at the Ludwig Museum in Cologne, that also acquired her few existing works. The curator Massimiliano Gioni included Barlow’s works in the 2013 Venice Biennale, in 2014 she received the prestigious annual Tate Britain Commission, and since 2011 she has had several shows at Hauser & Wirth. The gallery prices have increased more than five-fold; they were low at the very when they started the cooperation. As we all know, Barlow is going to represent the Britain in Venice this year.

As of 2010, a radical shift occurred in the institutional and market attitude toward Barlow, who, despite having been active for forty years as an artist and teacher, was largely ignored until then. This shift was mainly caused by the fact that she was taken up by one of the leading galleries in the world, which had an extensive network among collectors and institutions. Consequently, the question should not be why this radical change in visibility occurred, but why Hauser & Wirth chose her at the age of sixty-six.

The explanation should be sought in growing collectors’ demand. As their numbers increase, leading galleries need to expand their programs with new artists in order to serve their clients. Barlow, who built up her autonomous oeuvre and was part of the postwar artistic scene in the UK, is an artist whose art could be presented as a discovery and, at the same time, as a high-quality safe buy, more than that, a work that carries a financial potential, proved by price increases already. Her oeuvre reflects various phases of the art history of the second half of the twentieth century, including the formalistic break in sculpture, but her being a woman justifies her lack of visibility in the older system, which can be corrected now.

The first reason, thus, for the sudden interest in the older women artists is the market’s big appetite for new, whereby new doesn’t necessary mean young. Collectors, who are the driving force in the current art market, are permanently in search of new artists who will fulfill their expectations of artistic creativity, deliver high quality works, and, preferably, gain importance in the history of art. At the same time, they often seek artists who promise growth not only in terms of artistic value but also in price. Barlow and other women artists fulfill these criteria, as the below examples show. Mira Schendel could be seen as an important voice of her generation connecting Europe and South-America, working across continents, countries, and languages. The Swiss-born Schendel immigrated to Brazil in 1949 where she became an important avant-garde figure, not only a visual artist, but also a poet and cultural driving force. In her drawings, installations, and sculptures she incorporated many elements that had informed her life: raised catholic but of Jewish origin, she was open for an undefined religious spirituality; as immigrant she knew the power of a language and sign systems. Her conceptual works connected with the concretist and neo-concretist movements in Brazil but have never belonged to them strictly. In case of the late Schendel, her oeuvre is complete, her institutional presence justified, so the task of the gallery is to shine their spotlight on the works and convince collectors of her art-historical relevance and big potential to grow.

Carmen Herrera is known for her rigidly geometric abstract paintings in which she experiments with the simplest pictorial arrangements. She uses contrasting colors, mostly a combination of two that are organized in geometrical forms painted with barely visible brush strokes. Born in Havana in 1915 Herrera studied architecture in Cuba (1938–39) and art at the Art Students’ League, New York (1942–43). She exhibited alongside the great names of twentieth century modernism such as Theo van Doesburg, Piet Mondrian, and a younger generation of Latin American artists, such as Brazilian concretists. In 1954 she settled in New York; she was the friend and neighbor of Barnett Newman, but up until the beginning of this millennium she had apparently not sold a single painting and her work was virtually unknown in the art market; her first work was sold in 2003 by the dealer Frederico Sève in the context of South American art. At that time, nobody could have imagined that the Gallery Lisson would open their New York space in 2016 with a solo show of Herrera’s work, followed by a large-scale survey at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. The price of her work has risen vastly during the last three years.

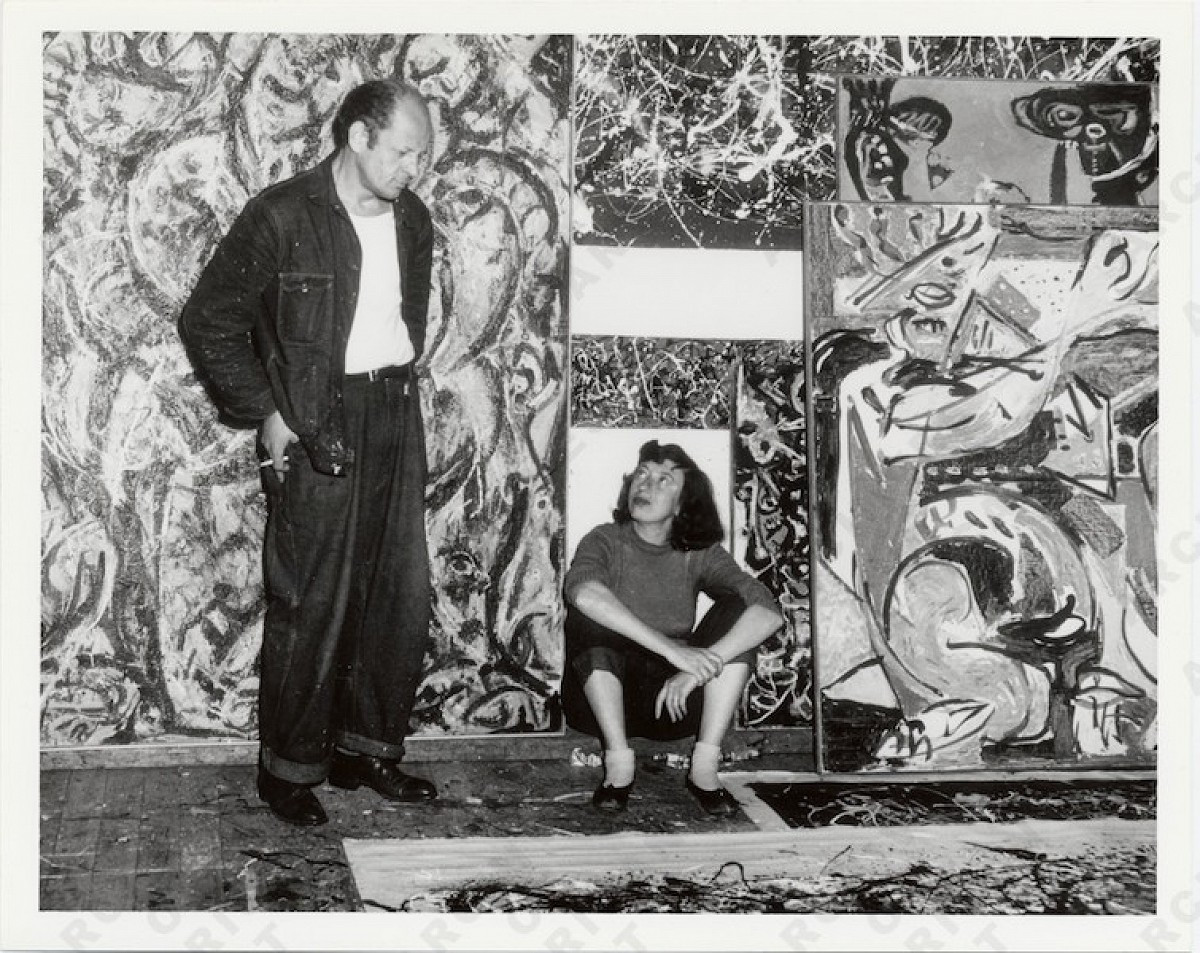

These artists offer mature material and strong connections to already recognized artists and movements, which in the broad network of experienced gatekeepers can be turned into artistic and market significance. This is of course not limited to women artists, but women artists also offer another important story, the story of vindication. This is the 2nd important reason of the strong interest in older women artists. These women were previously unrecognized by an art system favoring men. The gallerist Rose Fried told Herrera in the 1950s that she may be better than her fellow male artists but that she would not show her work because Herrera was a woman. In 2016, on the occasion of her solo show at the Whitney, she was called a key player in any history of postwar art. Lee Krasner, who has been slowly recognized as one of the most significant abstract expressionists and whose estate has been represented by the Paul Kasmin Gallery since 2015, heard from her teacher Hans Hofmann about her work: “this is so good, you would not believe it was done by a woman.” This women’s fatal attraction is based to a certain extent on the idea of social justice. As the examples show, many or most women artists went unnoticed in the postwar era. Buying or showing works by previously overlooked women artists is a way to apply social justice and correct the wrongly written art history. For collectors it offers the idea of social engagement and a redress of social inequality that can add to their good reputation and prestige. For galleries, representing older women artists creates a political position and adds to their progressive profile, which in turn helps differentiate them from other galleries. Today, despite the Internet revolution, the art market system hasn’t changed a lot, so the main area of invention is not the gallery model but the gallery program. Therefore, women artists form a solid foundation for the galleries to be recognized as serious, socially engaged, and politically correct.

These last aspects also appeal to institutional actors who have been trying to impose gender and identity discourses upon the curricula of art institutions. There are many curators who came into power in the last ten years who positively discriminate women and previously marginalized groups, offering them visibility in public spaces. Rectifying the inequality and injustice in art history has become a beloved element in museum exhibitions. The Turner Prize had just abandoned any age limitations acknowledging that artists can have a breakthrough in any phase of their life. Although the women’s presence in art institutions remains a problematic issue, we have seen several corrections recently: in 2016, for example, the New Museum organized seventeen solo shows out of which fourteen were given to women. Tate Modern’s new director Frances Morris has criticized the art world’s “bias” against women, calling it “a boys’ club.” Consequently, Tate Modern opened the Switch house in 2016, showing Louise Bourgeois, Ana Lupac, Roni Horn, Phyllida Barlow, Marisa Merz, and other female artists. The Ludwig Museum invited the Guerilla Girls to come to its celebration of forty years of existence in 2016, which the latter took as an opportunity to criticize the museum for its dearth of exhibitions showing work by women artists. The 4 finalists of 2017 Prize der Nationalgalerie are all women, in this specific case young women. Various articles appear digging into art history to find the forgotten women artists. The fertile ground of social justice and political correctness that is pervasive in the art world today helps create circumstances in which the work of women artists can be exhibited in institutions, which make them highly attractive and irresistible to the art market.

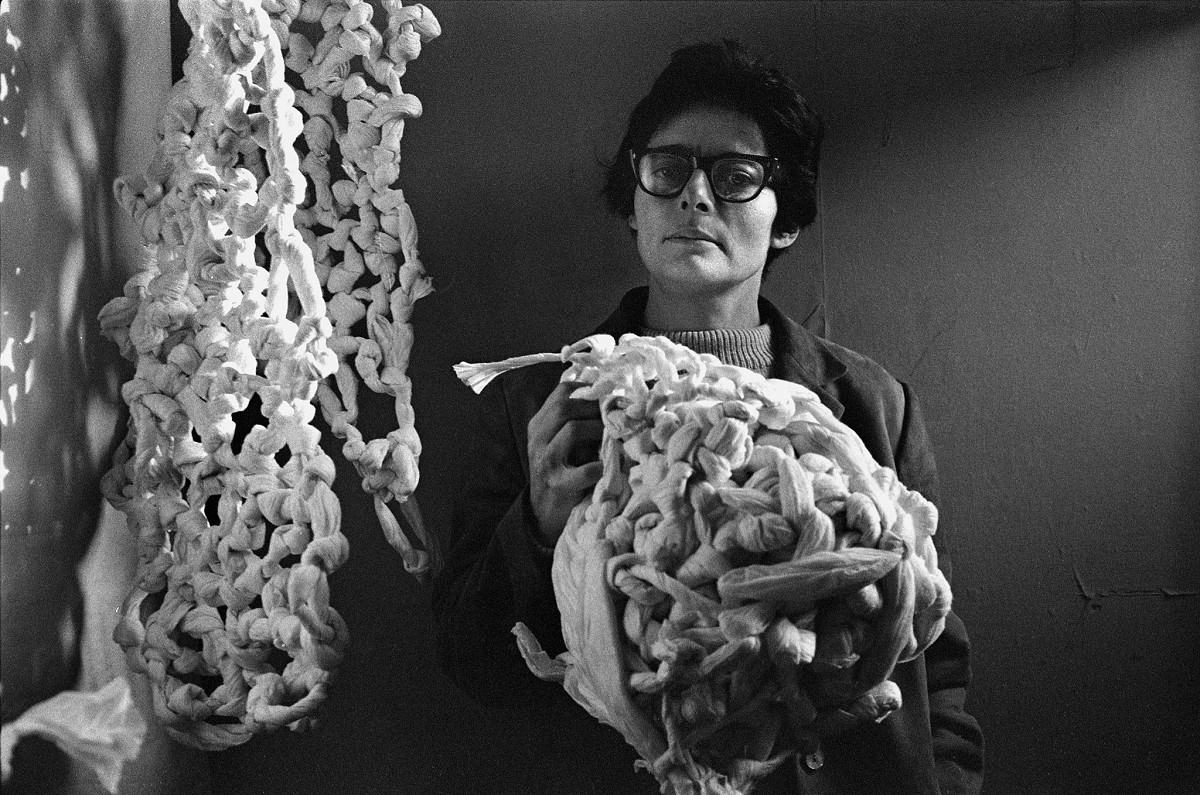

The next 3rd reason for the growing popularity of the women artists forms their personal and emotional narratives. The narratives appeal to the public imagination and help in constructing the artistic identity of the given artist, which is so essential in order to sell in today’s market with huge numbers of artists and galleries. There is for example a special aura surrounding Barlow’s art since her early works simply don’t exist any longer, or only as traces of material in her other works. This aura of the fragility could be combined with the personal myth of the woman artist who, against all odds, has continued to make art and believe in her work. Her previous lack of commercial success makes her a non-conformist; an artist pur sang who finally managed to gain visibility without making compromises. Rose Wylie is the beautiful talented artist who was prepared to offer all her talent for her family, but like a phoenix regained her strength and her place in the art world. Her lack of compromises, her coolness and nonchalance also makes her a role model for younger artists. How often have I heard, “I want to be like her when I’m eighty.” The female identity offers plenty of possibilities for making stories and playing around with notions of beauty and liberation. A woman artist can be a mother, a wife, a lover or a victim; in both way confirming and challenging. In the past, oeuvres of women artists tended to be interpreted as female; also in this regard there is a room for corrections. The work of Eva Hesse (1936-1970) has mostly been interpreted as beautiful, intuitive, personal and connected to her life as a woman, and later on as an ill woman (described as fragile, tortured, talented and wounded). Now you can use both; you can add to this female interpretation a more ‘neutral’ art historical reading, but the personal life story still hovers in the background. Hesse who died early, will forever be remembered as a beautiful and sensitive but since recently, also as a groundbreaking artist. These personal narratives of women artists create emotions through which collectors can identify with the personal or social standpoints embodied by or attributed to the artist, and add to their desirability.

Also, and this form another emotional element so important for the art world, they represent the classic model of art as a calling. This model grabs people’s imagination much stronger than today’s model of art as a profession. Their life stories are not only romantic and heroic; they also confirm the miracle of art, casting the art world as a place where the impossible can happen and where the reward for hard work can be earned against all odds. Older women artists are the art world’s Cinderellas, preserving its magic and allure. These characteristics are extremely important to make the art system function properly.

The last aspect that could add to the increasing importance of women artists could be the possibly growing base of female collectors, some of who seek the identification with other women. I don’t have any figures that could support this assumption, though.

Summery: The interest in older women artists is driven by the quest of collectors for new, high-quality work with a strong potential for growth. The mature oeuvre offers social, cultural, and very likely economic capital to collectors and galleries. The personal narratives are appealing and easy to identity with. They also support the art world as the extraordinary place where miracle can happen. The ideas of social justice and the rectification of inequality find broad support not only among collectors but also among institutions that add to the artistic value of given artists.