Gina Beavers

Published: September, 2016, ZOO MAGAZINE #52

MG: Despite having been declared dead dozens of time, painting is more alive than ever and it still elicits a lot of emotions. Recently two big shows – one at MOMA and one in Munich/Vienna – attempted to define contemporary painting. Do you think it is at all possible to define what painting is today?

GB: Well, painting today exists in so many different forms. For example, there is a whole world of paintings that happens on social media. When I was making paintings fifteen years ago, before everyone had a website, I would make something in my studio and think, “Oh my God, it’s a breakthrough!” I was the only person who saw it. Now you got onto Instagram and in ten minutes you’ll find a hundred people who are doing work that is similar to yours or on the edge of what you are doing. You immediately connect to all kinds of people.

MG: Are you connected or are you intimidated?

GB: It is more like a conversation. Making a painting is a conversation with other painters. The pace of the conversation has sped up so immensely though, that you don’t feel that it is possible to make anything that has not been made before. You might be only slightly original. We see each other’s works constantly and immediately. That sense of scale and that kind of organic proliferation defines the painting community now. How do you capture this?

MG: So you see a painting as a process of a permanent exchange with others and the final result as the sum of all that has been happening until the moment of fixing it?

GB: Absolutely, this part of it is insane. Every day there are so many artists followed on Instagram in the world. If I post something, it will be looked at; that pollination is crazy.

MG: This means that the originality concept has assumed a totally different meaning.

GB: It is much harder now to pursue “originality” than it used to be, for example during the fifties or sixties. The abstract expressionists were making a distinct innovation every few years, which functioned like a brand; Newman had his zip, Pollock his distinctive dripping style, etcetera. But now, every five minutes somebody is making an innovation that is cool, and then, five months later, hundreds of people are using it. I feel like the idea of innovation as an end in itself is sort of dying or maybe had to die in terms of art making.

MG: Is that the reason why you make paintings that look extremely solid? As the opposite to the whole process of thinking and exchanging that is so fast?

GB: Maybe, the imagery could be based on a kind of funny, rapid conversation, but the actual medium is a very solid, concrete thing.

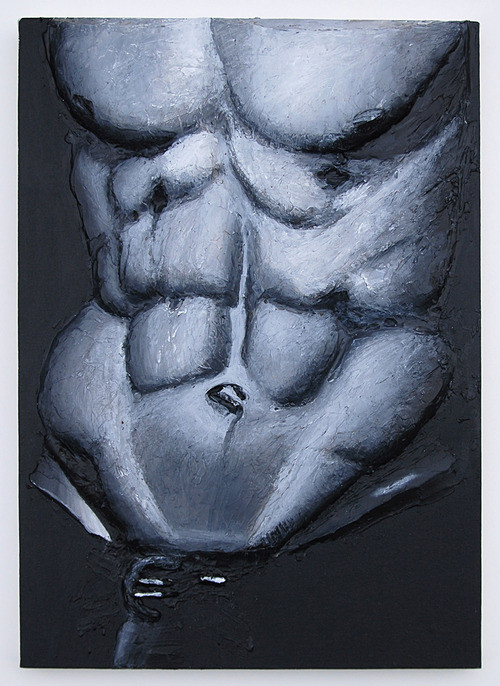

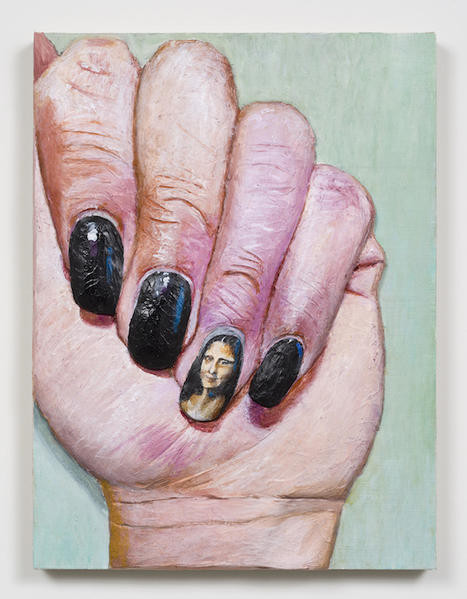

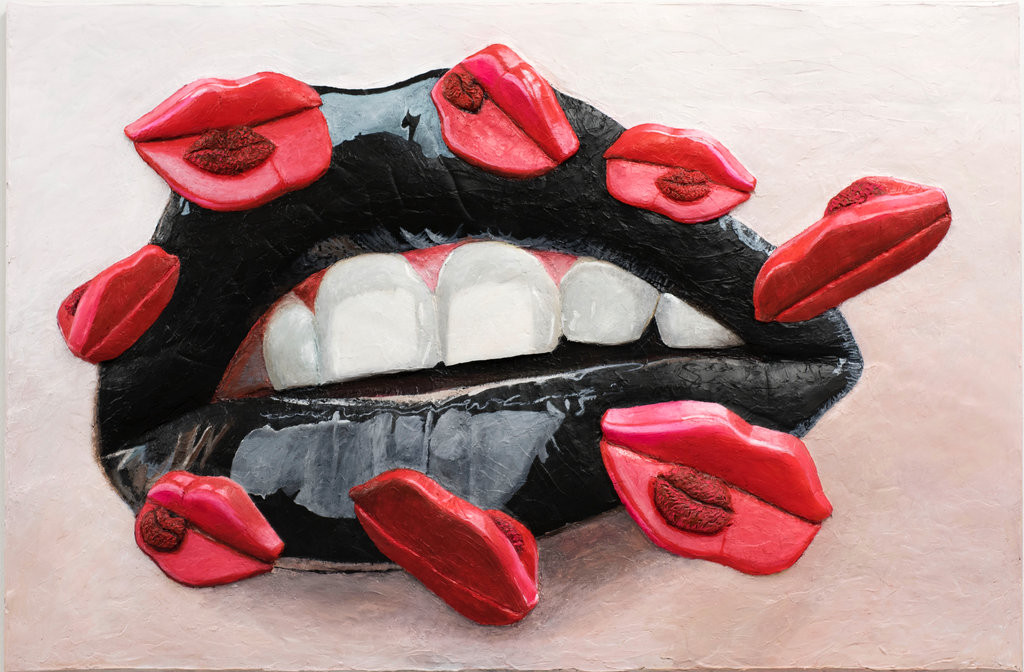

MG: Your work has certainly an element of innovation, which is your sculptural use of paint as material.

GB: It’s interesting because I didn’t really go looking for it. I developed that way of working through struggling with the heavy paint I use; it interferes with my skill. I’m taking photographs when I’m working on it; I’m stepping back and forth. It is a kind of a battle with the medium, which is challenging but also really satisfying. If I was painting flat with oil I could paint very realistically but it wouldn’t have this presence.

MG: I’m reading a book about the rivalry between Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, who had initially been good friends. In quite a nasty comment, Bacon said of Freud’s paintings that they were realistic but not real. I would apply this comment to your paintings but the other way round: they have this strange presence of realness but they are not realistic.

GB: They play that weird line; it could be that their language is more cartoonish. I used to be influenced by and make underground comics. There is something that satisfies me in pushing through to this photorealism, which becomes a bit creepier when rendered in 3D.

MG: Have you mastered the technique now?

GB: As I have gotten more into it and as I have wanted the layers to be thicker, it takes longer because of some engineering issues. Usually I have several works drying. It might sounds cheesy, but it becomes a very intuitive “dance” between the different paintings: this one needs this and that needs that. I have to be disciplined in giving them equal time though, or I could spend all my time on perfecting one.

MG: Does it need to dry for long?

GB: There are different layers of paint in each work. It takes about six weeks for the thickest areas of paint to dry to the point where I can stand the paintings up vertically.

MG: If we speak about the subject matter of your works, one common denominator for me would be human obsessions. I understand that you studied anthropology – that probably explains your focus on human cultural behavior, especially in relation to the body.

GB: Absolutely. When I first went to the college, I wanted to be a doctor. Because my whole family are educators and artistic people, they were so excited about my choice, that they would finally have a doctor in the family! I studied for a year and then decided that this is not for me, instead it became anthropology and art. I can’t help but think that some of my interest in the body reflects that early interest in medicine. The rest is the study of culture, that strange thing we are doing, looked at by an outsider.

MG: There is also a very strong relation in your work to social media.

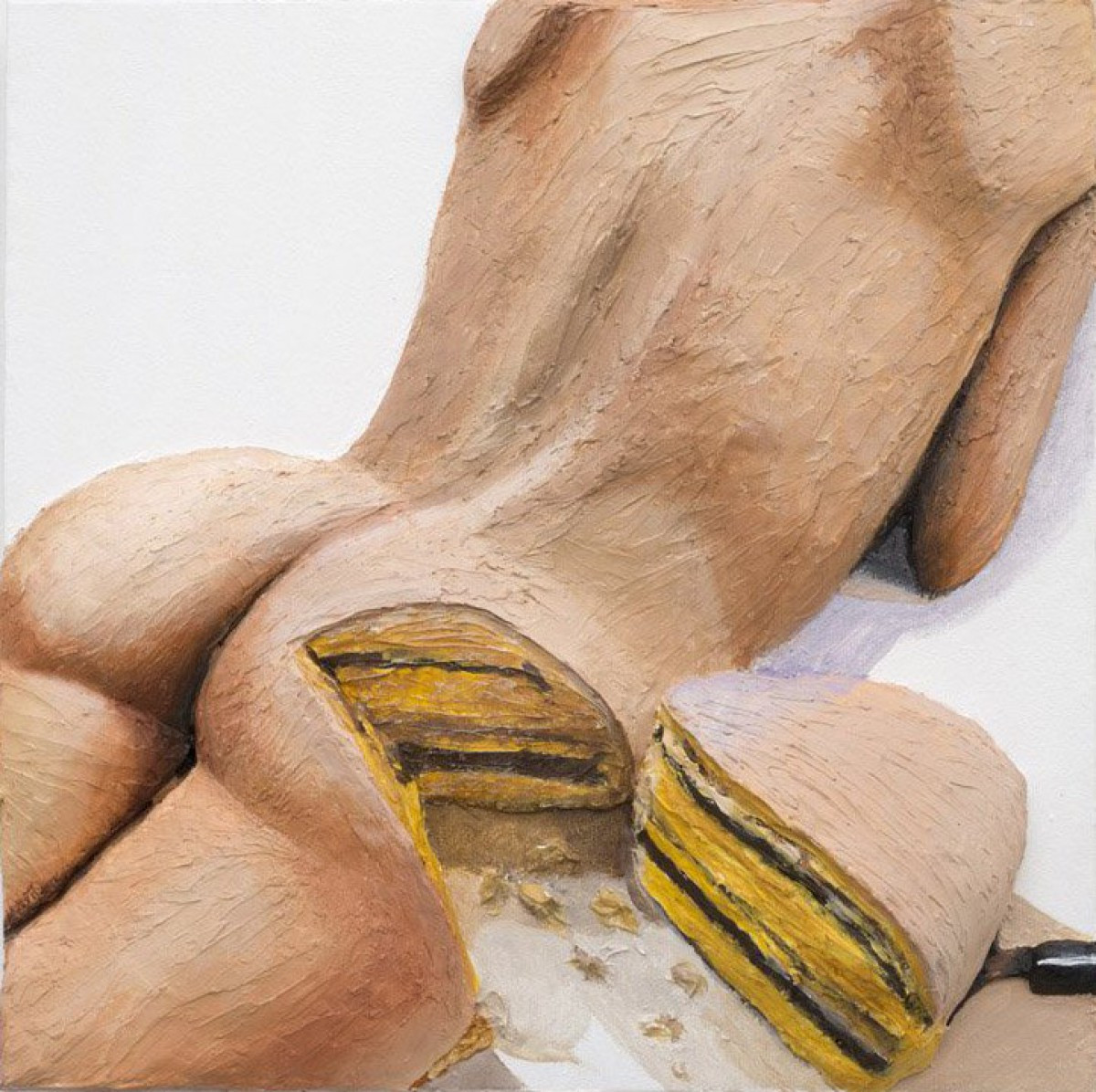

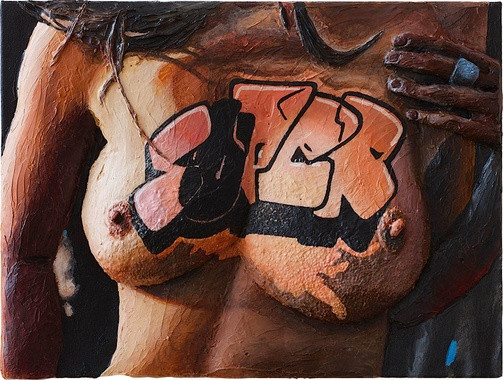

GB: Different series that I’ve done, such as the food paintings, were based on images from social media shared by people connecting through what they were consuming. More recently, I’ve been using images of make-up tutorials that users share and I also make work based on memes that are basically visual jokes. You can’t tell what is real and what is photoshopped and the images of bodies are often grotesque, interesting, and funny.

MG: You never paint yourself – you always paint other people.

GB: My work is autobiographical, but through others. It is a way through which I consume things but they say a lot about me: what I’m looking at, what I’m doing, what I’m collecting, what I’m thinking about. I have like 10,000 photos on my phone that I permanently keep.

MG: It is addictive.

GB: Before living this ongoing engagement with social media, I would walk through the city, see something interesting on the side of a building and make a painting from life. Then in 2010 I got my iPhone and all of my looking went into my phone. I guess it’s kind of sad but it’s just reality. There is more narrative in my work though, there is more text and conversation; it is more specific because all we do on social media is talk and argue!

MG: The year 2010 marked the turning point in your work.

GB: I moved away from abstraction. I discovered images of the body and food photography for myself. But in a certain sense I have remained a very traditional painter because I paint what I see. What I’m seeing now is on my phone so I’m painting that world.

MG: What did you paint before?

GB: My father has two paintings of mine in his study: one before I went to grad school and one after I graduated. The work before I went is a very cartoonish kind of narrative, not so different from what I’m doing now. The work after is a purely abstract painting – I used tape for the edges! In grad school I got heavily into abstraction. It was an important phase, but it wasn’t totally me.

MG: Do you think that in your case the artistic education pushed you in the wrong direction?

GB: If you’re interested in a subject, whichever field you are in, you should learn more about it. You don’t get that many opportunities in the real world to talk about your work in as in-depth a way as you do in grad school. Three hours a week to talk to really knowledgeable artists about your work is pretty amazing. As far as your actual work is concerned, it can be confusing because you are being exposed to many different people who are very smart, sometimes telling you completely opposite things.

MG: Has the study created an awareness of being an artist and being a part of a long tradition?

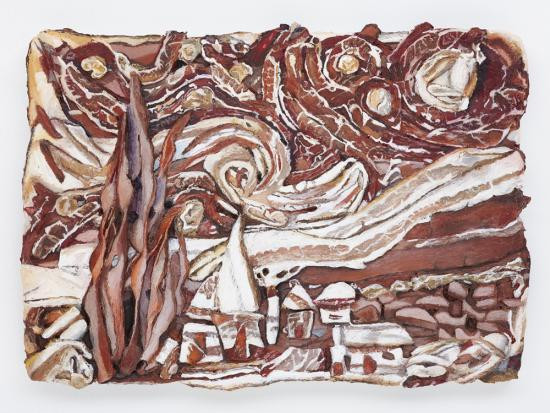

GB: When you are a painter you are trying to find a lineage or a place where you can insert yourself, you’re looking for something that is missing in the history of art, a different way of making a painting that is relevant, and it’s important to know that history. But, I have also been influenced, as many of us have, by outsiders. It’s like you are always asking: “Could this be a painting?” “How come that painting is considered good and this one is not?”

MG: I had the impression that with your paintings you are not necessarily mocking the academic tradition, but that you question the hierarchy of academia that is not necessarily right.

GB: Even when I was making abstract paintings I was making caricatures of abstract paintings; I think that came from my early love of underground comics. Even if you love and revere art, as I do – I grew up with art, I went to art museums when I was a kid, I love Starry Night! – I do think that when I began to study art more formally, I had a visceral, negative reaction to the kind of academic painting that is promoted in art schools and I felt I had to reject it and react to it.

MG: In 2010 you discovered the iPhone as a source of your imagery. Was it also around this time that you started to paint with the thick layers?

GB: This guy who makes this very heavy acrylic was working in my studio building. He’s an artist and he has a paint company. He was bringing me all his extra stuff for free and let me experiment with it. So I did, and it got me hooked on it. It’s a very high quality acrylic and very adhesive. Acrylic is a very experimental medium with many possibilities. Jack Whitten’s work and his exploration of the medium is a great example of this. Acrylic dries quickly. I could never ever make the paintings that I make in oil; the drying time would be insane. I went through many stages of experiments with it, cutting it, pouring it, mixing things into it.

MG: When you found your own language, you also started to get attention from the art world; you got exhibitions and important reviews. How did you experience the time before? You mentioned once that it is not easy to survive in New York.

GB: I had a full-time job most of the time. I worked as an art teacher at a school in Brooklyn for twelve years and I only quit in 2015. I should have left earlier but as a full-time art teacher in New York I was earning a very good salary and it’s hard to just let the security blanket go. I was working like a maniac though. Teaching children is demanding; sometimes when I showed up at school after three hours of sleep because I had an art deadline, these very New York thirteen-year-olds would tell me, “Ms. Beavers, you look really bad.” For years I worked full time. I would go out to openings, I was social, AND I had my studio practice.

MG: It sounds impressively exhausting. Why did you work so hard?

GB: When I got out of grad school, I didn’t know what I was doing; I was a mess. I had to find a job, pay my bills, and find a studio, but I was kind of like Sunday painter, and very intimidated. I wasn’t working seriously on my art. Then around 2006/07, I said to myself: “You know Gina, you have to do it, this is it.” And then I started to get more serious and it became very intense, partly I think I felt I had to make up for those lost years.

MG: What did you dislike the most?

GB: Teaching was so hard. It is very motivating now because I will do anything not to have to go back to teaching! I have to say though, I learned a lot during this period. You learn to deal with very difficult people, you learn how to be incredibly patient and everyday life exists like sort of an emergency room situation, where everything that can go wrong, will go wrong, so you’re prepared for anything.

MG: The exhibition Greater New York in 2015 at MoMA PS1 seems to be one of the game changers for you.

GB: I was very honored to be included in that show. The curators put me in a room with Collier Shorr, an amazing photographer, and they chose to show her editorial work. I was very happy with this photographical context. Sometimes people try to include my works in shows about funky painting aesthetics, and it doesn’t always work, my work doesn’t always connect. Photography was a nice change.

MG: Your work looks very different depending on whether you see it photographed or in person.

GB: I’ve seen some comments when people post my work on social media: like “What the hell is that” – people can’t figure out what they are looking at. I like that there are two forms of experience for my work, the existence online and in reality. That’s how many of us exist now as well. I like the fact that in photographs, the images look somehow animated because of the shadows they cast, but that they appear completely different when you show up in the gallery and see them in person. I work with photography a lot in the process of making them.

MG: There must be something that particularly interests you in these human obsessions.

GB: I personally never take photos of my food. I remember when I was growing up in the nineties Japanese tourists were taking pictures of their food with their cameras. I had a Japanese friend who used to do it as well, and I thought that it was the most hysterical, unique thing – why would you do that? Now 45 million photographs of food from around the world circulate on Instagram under the hashtag #foodporn.

MG: How did you get interested in these photos?

GB: My husband is a wine educator and he had a restaurant for a long time. So a lot of his friends were posting food photos from different restaurants and I was following them. They kind of operate the way art people do, going to art shows and posting photos of the artworks, except they’re documenting the food. I guess it’s strange but when I was making these paintings (depicting meat, hamburgers, and all different kinds of indulgent food) I was vegan. It’s interesting to pursue these subjects that don’t personally obsess you. I think that’s the anthropological view, to be curious but removed.

MG: Do you have the same attitude regarding the make-up series?

GB: Here I’m more interested in the educational aspect of it; the idea of learning how to paint step by step. The grid also serves to animate the separate images. I like how the painting is painting itself while looking at the viewer, in the eye tutorials. I don’t judge the things I’m drawn to paint, I’m really functioning more like a documentarian, documenting these corners of aesthetic experience on social media.

MG: How do you think your paintings function for the public?

GB: My paintings are often like one-liners. They reflect where we are in our cultural moment – where we don’t have time to read an entire article, we will often just react to the image. We have become really focused on reading images and their subtexts. The actual article may offer a completely different content but a lot of us don’t even get further than the headline. I’m looking at the image and the image is telling me the story, and the fact that you have chosen this image for your story is essential. This reading of images happens instantly, whether it’s a political statement, a news story, or gossip. What fascinates me is the images that cut through everything to motivate you.

MG: This is a central idea of your work – to find images that grab you.

GB: Sometimes I am unsure of how their narrative will operate in the painting. I find really good images in terrible articles with tons of ads. Often if you go to the bottom of click-bait articles, if you can wade past the pop-up ads, you will find the weirdest and most disturbing photos and photoshops. They are seemingly one-line narratives, and I never know how they will function on the wall in a gallery. Sometimes I’m very nervous because I’m just letting this thing out of the bag and I have no idea how people will react to it. There is anxiety, will people hate me for making this or laugh at me? Some of that is definitely the anxiety of the artist in any era, but some is tied to the reality of posting on social media.

MG: Speaking about politics, you mentioned that you are involved in Hillary’s campaign.

GB: Yes, I have been phone banking from her headquarters in Brooklyn, although I had to take a break recently because of more deadlines. It is very exciting, over the summer there were many high school kids working with me. They are too young to vote, but they were really great at cold-calling people, also lots of retired people. I’ve been trying to do whatever I can! I think that having a President who is a woman is important for American women and women across the world. I feel that a lot of women don’t even realize how this will impact them. The image of that is very important.

MG: Or the ultimate headline…You were born in Greece into a diplomat family, you’ve lived in several countries around the world – does that have any impact on your work?

GB: It’s funny because my European friends say that my work is very American. There is probably a part of my work that is trying very hard to be American – when you grow up outside, I feel like a little part of me is always trying to fit in. Then again, people who have lived here their whole life can also feel alienated. Living abroad, going to international schools, gave me a broad perspective of the world, which certainly brought me to New York. I could never live anywhere outside an international city in the US.

MG: How is this perspective reflected in your work?

GB: It has to do with me feeling like an outsider or a loner, which is one of the risks of moving every few years as I did. I also kind of had to learn the American culture. At the same time, my dad’s brother is an American cultural historian and my dad is an amateur historian, so I definitely have a curiosity about culture in my genes. There is that element of studying American life too, although food photography, make-up – these things are global. I think growing up among varied cultures and languages has contributed to the diversity of subjects I approach in my work – this kind of bubbling, broad dialogue of cultures.

MG: What is your next subject?

GB: I’m experimenting more with installations for my paintings. Last year at the Frieze art fair in New York, I hung my works on the insides of a cube. I’m trying different formations, to change the structure a bit. The installations operate like sculptures, but the paintings become their own entities when you remove them from the cube. It is partly a reaction to endless images hanging on walls in the gallery and online. How can I show images differently? I started with this at an art fair because I anticipated that feeling of exhaustion of seeing endless images hanging on endless walls. As an artist I’m trying to find out how I can react to this.