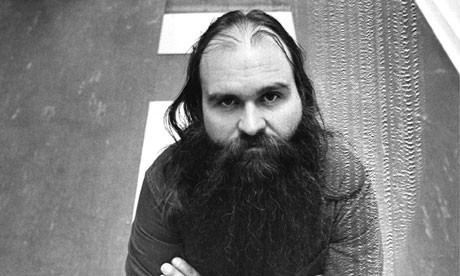

Carl Andre

Published: October, 2015, BLAU #4

Marta Gnyp: You belong to the artists who have not only witnessed but also defined the development of the Western Post-War art history. Where to start with someone who has had a career as yours?

Carl Andre: I was born in Quincy in Massachusetts, a very nice town made famous by revolutionaries like John Quincy, John Adams and John Hancock. Frank Stella who is from Malden, MA, said to me that the only thing he envy about me is the fact that I grew up in Quincy and he grew up in Malden.

MG: You both went to the Phillips academy in Andover.

CA: Yes, there I discovered my vocation as artist.

MG: How did it happen?

CA: It has to be between 1951 and 52. At Phillips academy there is a very serious museum of American art called Addison gallery of American Art: everything from early colonial paintings to Jackson Pollock was there. In the first year I took art as a minor, which meant two hours a week in one of their studios. There I was totally immersed in art.

MG: Which medium did you use at that time?

CA: I can’t draw and I can’t paint. My handicaps have been of a great advantage for me, but it wasn’t until a certain moment that I realized that. I was very lucky to know people like Frank Stella and other artists who helped me understand that I was only a sculptor.

MG: In which way has Frank Stella influenced your way of working?

CA:I never really had a studio. I was living and working in a tiny apartment in the Mulberry Street on the lower east side that I shared with the composer Mark Shapiro and photographer Hollis Trampton. The rent was 19,84 $ a month and there was no hot water. I used to call pretty girls and ask whether I could come over to take a shower. Frank told me that if he was not in his studio I could come there to work. So I did. One day I was working there doing some sculpture when I noticed some scraps of discarded canvas lying around. I got a couple of these patches, used paint from pots standing around and was sort of painting on them when Frank came in. He said: “Carl, if I ever catch you painting again I’m going cut off your hands”. He said it deadly seriously. Frank was a Sicilian – they say what they mean. I asked him why I could not be a good painter? He said: ‘because you are a good sculptor now, go and do your sculpture’. So I did.

MG: You had to listen to the Sicilian.

CA: Frank was and is a very brilliant person. He doesn’t speak often but when he speaks it is gospel.

MG: Were you always using your hands to make things?

CA: I’m not a conceptual artist although I have an inquiring mind.

MG: Why is it for you so important not to be categorized as a conceptual artist?

CA: Because I don’t believe that there is such a thing as a conceptual art. Art is mediation between human beings expressed through a physical object. An idea has no palpability for me. I endorse the comment made by the French physician Joseph Guillotine: all ideas are the same except in execution. I have desires; I don’t have ideas. For me it is a physical desire to find the material and a place to work. Then I can’t do anything unless I place the things together and create the work. I can’t sit and draw a model on a paper.

MG: Do you consider yourself as a Minimal artist then?

CA: I don’t mind being called that because I admire very much the work of Donald Judd, Sol Lewitt, Bob Moris and Dan Flavin who are considered Minimal artists as well. We had a community of artists at Max’s Kansas City, which was a bar in NY on 17th street and Park Av. The proprietor Mickey Ruskin was just in love with artists and their works. Artists and young intellectuals went to this large restaurant with wonderful steaks and lobster, an extremely lively scene and lots of beautiful girls. People talked to each other. All that doesn’t exist any longer. There is no bar scene in New York anymore.

MG: When you came to New York in 1956 a very strong art scene was the one of Abstract Expressionists who came together at the Cedar Tavern.

CA: Yes. I met Bill de Kooning there and shook hands with Franz Kline. They were very nice men and had no pretentions whatsoever. They were as much surprised by their success as anybody was.

MG: How were these communities functioning? You spent time together and drank together; were you jointly developing your ideas about art?

CA: The work wasn’t done collectively in anyway, but good art inspires good art. When Judd, Flavin and Sol did good art I didn’t want to make their art, but I wanted to make art as good as theirs. This is how inspiration really works.

MG: Were you somehow creating together the ideological program of your group?

CA: Sol and Donald never went to the bars. Don was a family man, had a wife and children and he was not a bar crawler as I was. Rob Morris wasn’t very often in the bars either. Bob Smithson was there with Nancy (Holt) – we used to have the most ferocious arguments; we could argue about anything, history, philosophy, science or poetry. People thought that we were terrible enemies but this was the way in which we loved each other. It was an expression of a great affection.

MG: Was your peer group reacting to Abstract Expressionism?

CA: That is a myth that has been propagated. As far as I know all the people that I spoke to were great admirerers of de Kooning, Pollock and Kline and other great artists of that time. But to admire someone’s work doesn’t mean that you want to make that work. Making art was a very private activity to me. Anyway; we were too busy picking up girls.

MG: For whom did you make art?

CA: For myself.

MG: What about your audience?

CA: Two or three times a year I would go back to visit my family in Massachusetts. I remember one night, my mother was sipping on her sherry and I was drinking my wine when she said to me: ‘Carl, I understand from what I hear form my friends that you are a rather well-known artist’. I said: “Yes, I can show you the reviews if you like”. “If you are an artist I would like you to make a work for me’. So I told her that tomorrow morning I would call the gallery and I would have them send her the finest available piece. ‘Not one of those floor pieces, you won’t!’ she cried. It seems my mother wanted me to carve her a seagull, which is a wonderful thing to do but beyond my capacity. My father on the other hand just thought I was playing a conman. I never talked with him about my work. My parents really never accepted my art.

MG: Did you attempt to explain it to them and other people?

CA: When people asked me what is the work about I would say: go and have a look at it. It is there; this is what it is. The only way to explain my work is to tell you the history of my life from my birth to the present time. It would be very boring though. A work of life is a product of a person’s life – the more surprising the life the better the work.

MG: Do you suggest that the personality of the artist matters for the quality of the work?

CA: Its not so much the personality, it is only a part of it. The id, ego and super ego; the whole human apparatus, everything you have done, all the people you met, it is very complicated. I have a greatly deficient imagination. If I had a good working imagination, I wouldn’t need to do my work at all. I make my works because I want to see what they look like. If I knew how they look like I wouldn’t make them. In the beginning I did make drawings but every time I went to a gallery or the space where I was going to work I had to rip up the stuff and start everything again. I realized that I shouldn’t think about the work until I have the material in me hands and the space where I’m going to work.

MG: Do you control what you are doing?

CA: You start laying down things and you don’t think anymore. A good artist is one with the task. There is no difference between the mind and the body.

MG: Do you give instructions how to install the work?

CA: Not really. I want to see what you do with my work. There are configurations and descriptions, to put the work in the corner or off the wall but the parts are not numbered and nothing is precise. It takes some sensitivity and a little understanding to do it.

MG: How radical was your work when you started your floor pieces in the ‘60s?

CA: It wasn’t radical to me but people were asking how can you call that art? Others thought that I was just trying to pull their legs. No, I was doing the best I could. People didn’t want to believe that. People believed that I was a hoax when I said that this is what there is. There used to be a wonderful good satiric comic program on the public radio in San Francisco which was called Radio Unnamable. My art is Art Unnamable.

MG: What about the critical reception of your work at that time?

CA: Some critics were very perceptive and enjoyed the work such as Eugen Goossen, Lucy Lippard and a number of others. I once run into Clement Greenberg very late at night in an artists’ bar where he was just alone and had quite a lot to drink. There he sat: a giant of art in solitude and despair. I came to him and said: “Mr. Greenberg, I’m Carl Andre.” He said: “I know who you are. By the way please call me Clem, everybody calls me Clem”. So then we had a couple of drinks – he liked very much to give tips to artists – he said: “I just got one thing I’d like to tell you. Stick to copper.” To which I responded: “That was what my mother said”. My mother collected copper bottom pans. Clem didn’t like that.

MG: Did you get a lot of angry reviews?

CA: There is no such a thing as bad publicity; any press agent will tell you that. Your success is measured by how many lines and how much space you get. It is exposure that counts.

MG: How important to you and your group was the exhibition Primary Structures in 1966?

CA: That came afterwards. The art was created before the movement got a name and recognition. Usually it takes some time before an artist got recognized. I knew the show was over when my art started to be taught in the art schools. Kids were being told that when they want to be rich and famous you should make a work like Carl Andre. Then it becomes like a trademark. The late ‘50s and ‘60s was a wonderful time. People were doing their own exciting things; there was no money in it. Money is a murderer. There was more freedom because there was no market; market forces are very strong. I have never made a work of art in my life with the idea of selling it.

MG: Did you think about becoming a trademark when you got a retrospective in the Guggenheim Museum in 1970?

CA: To me that was the ultimate privilege. I think that the Guggenheim museum is the greatest work of art in New York. Frank Lloyd Wright was one of my heroes and to work in his space was one of the greatest gifts given to me, especially with Diane Waldman who was the curator. A few days before the opening of the show the director of the Museum Tom Messer arranged an appointment for us. In one of his private offices he said to me: “Carl, you have to understand that I hate your work. I think your work is an insult to our museum”. He said that it was only because Diane wanted the show that he agreed. Diane must have had something on Tom Messer, something like he was molesting boys or worse (he laughs).

MG: Why do you think he told you that?

CA: Messer means knife in German; he wanted me to feel the twist.

MG: How was the reception of the show?

CA: The opening was very crowded; a lot of artists and hipsters were there. People were still asking where is the art while standing on it.

MG: Would you agree that between Primary Structures and your retrospective in the Guggenheim you had become one of the dominant artists in New York?

CA: Not really. The dominant movement was Pop art by far.

MG: How was your relationship to Pop Art?

CA: I loathed Pop Art but Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein were very decent people.

MG: They probably loathed your work.

CA: It really wasn’t an issue. Artists do what they do. You don’t worry what the other artists do. You may envy the fact that they sell and that they have shows. I think this is true when you are a serious artist.

MG: Speaking about the sales: many Pop artists were making careers with Leo Castelli. Did he ever approach you to work with him?

CA: Castelli was a very great dealer and great gentlemen. Frank Stella had a show very early with him. After he became well known, Frank made an appointment for Castelli. I don’t think that Leo ever said ‘no’ to anybody. What he said was: perhaps next year, we will talk. He was a wonderful man. I didn’t mind because I had a very good relationship with the galleries I did show with.

MG: You were very early showing with the gallery Konrad Fischer in Germany.

CA: I had the first show in his gallery in Düsseldorf. Actually he wanted Sol Lewitt but Sol was not travelling. I think Sol might also not have wanted to show in Germany at that time because he was Jewish. This was not a problem for me. I knew the history of Germany as well as anybody else but the people I dealt with were children during WW2. They were as much victims of the war as anybody else.

MG: How did Konrad Fischer find you?

CA: He read Artforum and this is why he knew about what was going on in America and there is where he saw my work. Then Kasper König recommended me to him. As Konrad didn’t travel, Kasper was his agent in America. When I agreed Fischer told me: “you are not my first choice, Carl”. Everybody always told me: you are not my first choice Carl. Well, I’m here, as we say in baseball: I’m ready to hit the ball.

MG: How did you experience Düsseldorf at that time?

CA: Dusseldorf had a more lively art scene than NY at that time. Everybody knew everybody else. Joseph Beuys and the galleries of Fischer and Schmela were very active. I was very lucky to be there. If you have a choice in life between being good and being lucky – be lucky. There were a few wealthy collectors but money wasn’t an issue at all.

MG: You had to live on something though.

CA: I sold enough work. I have always lived very simply. I could never drive for example. A lot of things that other people consider as necessity I don’t have any need for at all. I never felt particularly deprived. I just was interested in having good time.

MG: What do you think about all the theories on Minimal art referring to the integration of the viewer in art or lack of historical references in the works?

CA: They are all bullshit. It is completely false. Think of Brancusi or Stonehenge. Neolithic art is all abstract. People who say that just don’t know history. Neither do they see the pleasure. Americans have a problem with pleasure.

MG: Not only Americans.

CA: I know only Americans. Art by the dead people is all right with them; art by living people is suspect. The pilgrim founders of America were puritans, people who denied the flesh. To me pleasure is contrary to every puritanical principle. You can spend your life indulging in pleasure. You are an artist because it is a pleasure to do it.

MG: Do you associate your art with pleasure?

CA: Completely!

MG: The experience of your art is very rigorous.

CA: No to me. I like what Henry Moore said when he was asked how he gets his brilliant ideas for works, which are so advanced, so powerful and unique. He said: ‘I just continue to do as an adult to do the things that I was doing when I was a child.’ I do that as well. Kids do the blocks, and little kids are great artists until they learn to read.

MG: What about the idea of development or progress in your work? In 2010 you were making works that are comparable with works from ‘80s and ‘90s.

CA: What is worth doing is worth doing again and again and again and again; as long as it is worth doing. Worth doing means gratifying to me – if it ceases I would do something else. Of course nothing surprises me more than finding the people who are willing to pay money for it.

MG: A lot of money nowadays. The work I saw yesterday in your gallery Paula Cooper cost more than 700.000 US$.

CA: That’s the resale and auction market; it has nothing to do with me.

MG: You don’t make new works?

CA: I formally announced that I have retired.

Melissa Kretschmer: Last month we discovered two boxes of small material that Paula Cooper gallery was storing for years. The gallery was always hoping that Carl would come over and make new pieces in the gallery. Carl keeps working with this material during the day at home. He made 19 small pieces in the late 2014 and early 2015. I will come home and he will show them to me, I take measurements and photograph them. What is nice that he doesn’t have the pressure from anybody.

MG: At this moment Dia Beacon is showing a large retrospective of your work. However, during the last 20 years there were not many institutional exhibitions in the USA of your work as your artistic stature might require. Did the accusations of your role in the death of your 3rd wife, the artist Ana Mendieta, block partially your institutional career in America?

CA: It blocked me for a while. It was a great shock and a great tragedy.

MK: Over the years I’ve got emails from complete strangers saying how can you possible live with this man. There was a demonstration in front of Dia’s offices right after the opening of Carl’s show; it was small but disturbing.

CA: I find that people who dislike me most are the people who have never met me.

MG: Ana Mendieta has defined a big part of your life. You were both artists but you were making totally different art. I also heard that you were both of totally different characters.

CA: Absolutely. Ana was a fantastic artist and a fantastic human being; she was a very high-spirited personality. She was very outspoken and would tell you or anybody exactly what was on her mind. Some people didn’t like her at all because of this. She was not an obnoxious person but some people were afraid of her. But we had some wonderful times together.

MG: You came from different cultural backgrounds.

CA: Ana descended from a very distinguished family from Cuba on both sides. Her grandfather was a president of Cuba so they left the country because they objected to Castro. They were not Battista people at all, but they did not agree with the Castro regime; they were prominent not among the contras but in the non-Castro community.

MG: Could you understand the nuances on Cuban relations and culture?

CA: We travelled together to Cuba. Ana loved Cuba and everything about it. She spoke Spanish even more elegant than she spoke English. I liked Cuban people very much and didn’t feel that I was in a totalitarian country. I understood of course that the model of behavior was simple. If you are against the revolution you have nothing, if you accepted the revolution you were a free person, at least in the 70s.

MG: I’m surprised that you could travel there as American.

CA: You went to Mexico and then you put your passport away so there was never any stamp in your passport showing that you visited Cuba. It was the time of embargo, Cuba had a lot of difficulties but they kept going because Venezuela was very sympathetic towards them and delivered a lot of oil. They flourished under restricted circumstances. Ana and I had wonderful time in Cuba.

MG: You still live in the same apartment in which you were living together when she died by falling down from the window. Do you have any memory of this?

CA: No. I was asleep when it happened. All I hear was just ‘no, no, no!’ Ana was trying to close the window. The temperature dropped by 20 degrees at night; there had been like 85 degrees and it went down to 60 in a very short time. She was very sensitive to the cold when I was not, so she got up at night without waking me up. Ana was 5 ft. tall so she had to get up on a window bench. She was trying to pull the window close and lost her balance. I heard her saying “no, no”. It was terrible.

MG: How could you put yourself together and continue working after such a tragedy?

CA: Well, you have to go on. There are disasters in our lifes but you have to go on. I had the support of friends; I found out that I had friends I didn’t even know about. Of course for the most militant feminists to this day I’m the monster. And I will always be.

MK: People have this really weird picture of what kind of person he is. Many years ago we had a dinner with a friend who I had known for years. He called me the next day and said: oh my god such a wonderful evening and Carl is so different than I thought! So I asked him where he got his impressions from when this was the first time he met him?

MG: Melissa, you are now the fourth wife of Carl.

MK: And the last one!

MG: No doubt about it. Nobody speaks about the first two; were they also artists?

CA: Rosemary Castoro was the number two and Barbara Brown was number one.

MG: Why did you always like to marry your girl friends?

CA: It was a time in America when girls felt more secure when they were married.

MK: We have been together since 1995 and we finally got married in 1999. We realized that firstly we will always be together and secondly that this would be easier to protect the art works.

CA: There are good legal reasons to be married such as the estate questions. With husband and wife if one dies there are no problems of inheritance because all goes automatically and you don’t pay a tax.

MK: If we wouldn’t be married and something would happen everything would go to the family of Carl, who would have no idea what to do with it.

MG: How did you two meet?

MK: When I went to NY I exhibited in the Julian Pretto gallery. Julian was a great person; he had no money and lived under the radar as far as the government was concerned. He had a little space in the Sullivan Street, where he had a two little programs going on: he was showing artists like Carl, Sol and Allan McCollum and he gave people like me first shows. People wanted to show with Julian because he had a great eye, was a very good person and very lively company.

He also always paid his artists first. The first thing he ever sold of mine he called me and asked me to come to the gallery right now. It was always cash. He said: if you don’t come to get it now I might spend it. He put it in two piles and asked me to put one in my bag and one in a back pocket, in case something would happen.

MG: You had a show together at Pretto?

MK: We had met each other on and off but we never got to know each other until after Julian closed his gallery in 1994 because he was suffering from AIDS. Sometime after I was having a show in another gallery, Carl sent a postcard and invited me for dinner but for four months after that I didn’t hear anything.

CA: I didn’t know how to get in touch with her.

MK: He was leaving messages in the gallery but they wouldn’t pass them to me.

Finally I ran into Carl during an opening in Tribeca. He invited me to a dinner with friends and that’s how it started.

CA: That was the best thing that happened to me in my adult life. I’m still alive because of Melissa. When we met I was more or less drinking myself to death. It is not that she said anything about my behavior at all, but here was this person sober and here I was making the fool out of myself. If I hadn’t had Melissa in my life I wouldn’t have very long.

MG: What do you think is the importance of your art in the perspective of time?

CA: I have no idea. It is important to me.

MG: Why do you think your art landed in art history books?

CA: You have to be in a right place in the right time. I wasn’t the only one; there were Judd, Morris, Lewitt, Flavin. I was very much attracted to Taoism, which is a sort of Chinese philosophy; there is a thing in Taoism about the uncarved block. The uncarved block is wiser than the carved block because the uncarved block can be many things and the carved block’s destiny has already been determined.

MG: The rumors have it that it was Frank Stella who pointed out for you at the possibilities of the uncarved block.

CA: I was carving in Frank’s studio when Frank came in and said: “that is very good”. He ran his hand down the uncarved side of the block and said “but that is sculpture too”. I took that to mean that the uncarved block could be as much sculpture as the carved.

MK: Years later when Carl was recalling the story Frank started to laugh. When Carl asked him whether it is not true he said: “You still don’t understand: I wanted you to carve the other side.” That is a nice story but it shows the shift in the ideology of thinking about sculpture that made you important for art. I believe that you are one of the people who changed sculpture.

CA: No, I added to it, not changed. Things change all the time. On the other hand somebody said: the more things change the more they remain the same, which to a certain degree is true as well. There is this wonderful woman who lives in our building and who wakes me up in the morning around 10 am. She makes sure that I’m up and that I function; she gets me the New York Times, she gets herself a coffee and a donut and comes back. She would sit here and talk; she is a very good friend. This morning I wanted to express my gratitude so I made a little sculpture for her. She was delighted and I was delighted. That for me is why my art is made.