Mark Bradford

Published: November, 2013, ZOO MAGAZINE #41

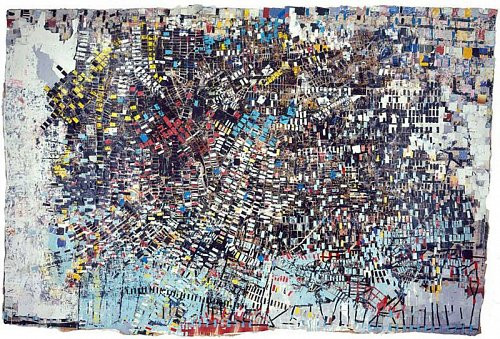

The American artists Mark Bradford is known for his big abstract paintings combining stunning classical beauty with the urban collage technique. His artistic development has been as exciting and uncompromising as his personal life.

Marta Gnyp: There is this amazing story about you working in the hair salon of your mother as a teenager. It must be quite important for you because it is almost the first information you get once you open your website. What did you do there?

Mark Bradford: I was a hairdresser, my mom was a hairdresser; it was a family business.

MG: Were you also interested in fashion?

MB: It was in the eighties and I think I was more interested in club-life and disco. I didn’t go to university, and if you didn’t go to university you go to the streets.

MG: You had no interest in art, no interest in social issues and politics. How did art get your attention?

MB: Well, I was engaged in a certain sort of outsider culture with all these freaks, which my friends and I were, and then I thought what do I want to do with my life? I knew I didn’t want to work in a hair salon. That was my mother’s dream. I didn’t realize it at that time, but people I knew were all kind of performance artists. We would make costumes and dance routines, but there was no name for it in the eighties, not in the black community at least. So I thought, well, the only things I seem to be interested in are creative things. And that naturally led me to going to an art school.

MG: So what you called freak would be called today a performance artist?

MB: Maybe… We were just young and enjoying life. It were the eighties, AIDS was everywhere, so everyone thought we are going to die anyway.

MG: Did this omnipresence of AIDS influence the style of your life?

MB: I think so; it was very Caligula. Well, you grow up, as a child you wonder what the life would be and what world you would inherit. And then you become eighteen and you want to take risks and you want to take drugs, you want to do what every other generation has done. And suddenly this new disease takes that away. And you deal with being young and old at the same time. You are dancing with a friend who has a diaper on because he has diarrhea that won’t stop. It’s both. And you are eighteen or nineteen and you can’t process so much death. My way was to throw myself into this kind of mentality, which was what the doctors were saying, everything is going to die, and it is just a matter of time.

MG: I assume there was also a social disapproval of the way of life that presumably led to AIDS?

MB: It was very much ‘the bad people got this disease’. The people who were bad people, were fringe people, gay people, people who didn’t care about the rules. So I thought, well, that would be me. So I think it just became a very expressive time for me, as the death was always there. The nineties were starting to be more political and the government finally started to acknowledge that, but in the eighties there was none of that.

MG: Would you say that the eighties have formed you? Not least because of the confrontation with the death and excesses?

MB: Absolutely. The nineties were cool. I went to CalArts (California Institute of Art) and discovered reading and learning about ideas. Foucault was an eye opener to me; I started to discover ideas.

MG: You started relatively late your art school at CalArt, it was only 1991. When did you decide that you needed this education?

MB: Well, a girl needs to know when to get off the bar stool, you know. You can’t spend your whole live in the clubs.

MG: What made you decide to go to school?

MB: In the eighties I was hundred percent convinced that everybody would die…I was one of the first hundred people who were invited for an experiment to take an AIDS test when they developed one. At the beginning they didn’t even have a test. They took us to this military bunker, it was crazy. There were no real writings about the mechanisms of AIDS; how saliva or sweat could work… it was more hysteria and propaganda. And all I saw were people dying. I was seventeen and I absolutely believed that we would all die. So when I lived through it I went to school. I think the social part of my work comes from this time before I went to art school. The abstraction gives me room to develop my own ideas around certain issues.

MG: And then during the nineties with some help of the French post-structuralists you managed to conceptualize your thoughts and ideas about social relationships.

MB: Firstly I had lived it and after I found sort of theoretical support for what I already had done. I did it backwards. I lived and then went to school.

MG: Is this the reason that the social aspect is so important in your work?

MB: For me I see the social aspect has to do with the body and it has to do with the ideas of the times that we live in and engage in. For me that is as important as the art world and the ideas that circulate in the art world. I feel that is neither this nor that; I just never choose one side. I engage so much with the politics of my time and some social, cultural and racial ideas. I couldn’t raise it when I went to school, back than it was almost impossible.

MG: You stress the social aspect also as the opposite to the tradition of the sublime painting. You seem to be absolutely against reading or looking at your art through metaphysics.

MB: Oh absolutely, I don’t know what I would be channeling or where it would be coming from. My work is very much grounded in my time and in the ideas that I am thinking about. This is why I use paper because it is a container for information, it has a memory, it’s an unforgiving material and it has to do with labor, and again the performance of the body is very important to me. I find that American abstraction especially the expressiveness of the New York school has totally different motives. For me, being black, should I say that I am channeling this kind of native American narrative or that I am channeling this kind of dark and wild person? If you turn it around, if I am black, what would I channel? It completely falls apart, the white side of my sublime or my unconscious white; it doesn’t work.

MG: You don’t want to be associated with the white abstract narrative at all?

MB: I wanted to engage that narrative. Abstraction historically belonged to certain people, white males most of the time. But I want to push that open a little more and to push it open a little. I don’t think anything exclusively belongs to someone.

MG: From the formal perspective, your work lends itself perfectly to be put in the traditions of abstract expressionism. It is probably unavoidable that art history would put you in this tradition.

MB: And that’s great. I have absolutely no problem with that. Because I think it expands the traditions, of who can participate in that tradition and who can’t participate in the tradition. I think it adds another layer to it.

MG: You stress the social aspect of your work and the communal aspect: do you think that your art can have a role in community? Do you think that your art can change something?

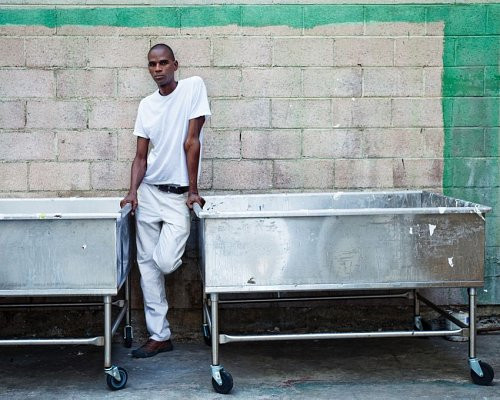

MB: In the community where I live, I don’t know if the art can change anything, I never think of it that way. But I know that the resources from the art can. I have a foundation that I work with, that I started here very near my studio. And I wouldn’t be able to do that if I hadn’t the career that I had.

MG: What kind of foundation is it?

MB: It’s called Art & Practice and basically it connects art with orphans. We use contemporary ideas to create an educational platform for those foster kids, so they can work in the exhibition space, they work in the library, and we developed a program for them.

MG: Why did you choose to work with those kids?

MB: I have a long history with foster kids. It’s something I have always been interested in. It is about them being outsiders, just because of the way that they were born, outside of tradition and because now they don’t have parents. I am just trying to create a kind of conversation and dialogue between the arts and the service side of the community. It’s been very successful. It’s great. We have been talking about the social side of my work and the sort of art side of my work and I wanted to create a physical manifestation of those two ideas.

MG: The social effect of your work is thus created more by using the money you earned with your art in social projects related to art than by creating an experiences by looking art your art or engaging in theoretical discourse. At the same time by doing your work you defy some art historical notions of abstraction.

MB: Exactly. I think that art historically, pushing the can of abstraction open is a thing I wanted to engage in. There are a number of African-American painters or abstract painters who were erased out of the history books and who are now being re-thought and being put back in history like Jack Whitten. The same thing applies to women, where were they? When you read about abstract expressionism, there are only a very few women mentioned. I think history should always be remapped, re-questioned and rewritten. I don’t think that it should be this static thing.

MG: You said that the kids are kind of outsiders. Have you felt being kind of an outsider?

MB: I never felt that I was an outsider, I felt totally fine. I felt that in many areas in school I was coined outsider, I was attacked, ‘this one is the strange kid’, and I was not participating in the center of power. And the sense of having to sort of navigate when you don’t play by the rules so much, that’s something that I was very familiar with, very early. Yes I was worried, yes I had hard days, but I always thought that I was freer. My mother raised me that way.

MG: Do you confront people with their judgments?

MB: I love to make people aware of other things than the large conversation of those who are politically correct and their behavior is correct. You can compare with someone who has got five puppies but has only enough room for four; the last one gets left out. I love to throw light on that one. Because the struggle that that person has to do in order to make it, by itself and not with that much support from society or the neighborhood in what he grew up in, or the schools that he was going to. My story is the one of the little puppy that you drop in the dessert and it comes back. It relates to the foster kids, because they had very difficult lives and lived in very difficult situations, their lives are filled with a lot of sexual abuse, replacement. I think it’s healthy for us to look at it and ask how can we bring it into the conversation? My mother was a foster kid so I grew up with this idea.

MG: People in your area probably look at you as some kind of a miracle.

MB: I don’t think they look at me as a miracle. Nothing has changed; they still think I am strange. My career is just as much a mystery to me as to them…. I never think about…I’ve been on my own so long and had to figure out things so much, I am kind of a one man show.

MG: How does this success feel to you? When did you feel that this success was coming to you, this kind of excessive success?

MB: I won the Whitney Biennale prize in 2007. And I was very surprised, I thought oh..that’s interesting. To say that I don’t really think about it is not a hundred percent true.

I will tell you how I think about it: when I was fifteen, I was a super strange little guy, doing whatever I was doing that day, and then I really grew a lot in one summer, I am over 2 meters, very very tall. I was super shy and a kind of awkward in my own little world at that age. But then I became a super physically standout kind of boy. And I remember how much I disliked it, how much I disliked the attention, because they told me like, oh you should be a basketball player, and I was saying: no, I want to do this, I am interested in this, so it became this two marks: what other people wanted me to be, and what I wanted to be. And this is what it feels like now having the success. For me I am just going to ignore it, if I look like a basketball player for the rest for my life fine but I’m not going to be one. And that’s what fame is for me: oh Mark now you’re famous, you should do this, or you should do that. I do what I want. I have been doing this so long that I just have been in control of my own subjectivity.

MG: So what is it that you want to do?

MB: I am doing the foundation and I want to do some interesting projects in Europe.

MG: Artistic projects?

MB: Yes. I like to do large-scale sculptures. I want to do something really interesting in the Middle East, I haven’t decided yet what. I want to make my own tiles, make my own… I am very curious.

MG: Do you work with assistants?

MB: I have one family that I work with. I have known them since they were little boys, with no art background. I have one assistant that has an art background when things go technical. But the Lopez family helps me, I have trained them up, they don’t know that I am famous, they couldn’t care less, which is perfect, I am just Mark.

MG: You became known for incorporating existing materials from your neighborhood. Do you still do it? Walking through the street to taking found materials to your studio?

MB: No, I walk around a lot and see the billboard but the material I use now is not coming from the streets, I didn’t want it to become some kind of urban myth “Mark” that becomes attractive. I use paper, period. I don’t just use urban material.

MG: And where does your interest in cartographies come from?

MB: I have always been super interested in explorations; I wanted to be an explorer and an archeologist. I traveled a lot, I traveled through Europe in the eighties, and I went everywhere. I love civilizations and the marks that they leave behind. I love to visit ruins, when you dig down there’s another culture on top of it, and another culture on top of that. I have always been attracted to this cultural memory. I like digging in memory. I have always liked cities and urban myths. My favorite thing is to walk on the street, any street, in Berlin, in the middle of the night though, always in the middle of the night. And I never like to go inside anywhere.

MG: But you don’t see a lot in the middle of the night.

MB: You do, you see little things. I like when things are closed up and I like the outside of the buildings, I don’t like the insides of homes. I never have the desire to go in. In a city like Amsterdam for example, I can walk on canals but I never like to look inside what is behind these big windows. I love industrial areas. I have always like public places where people have private conversations. I never like private homes.

MG: This is interesting. I just saw your painting in Centre Pompidou, and it was so full of light. I can’t imagine that you prefer a city in the night because I associate your paintings with light.

MB: Isn’t that funny? It is very difficult to differentiate the color at night. I like that; when I am in the studio and I am working really deeply with colors, I’m trying to see the difference between a black and a black, it’s very hard when you are using paper, so the way shadows hit a very dark building at night feels very much the way papers responds to each other. It’s very hard to have translucency, to have depths, to have movement. It is easy to do it in the daytime, but really to have paper look like it is paint, you have to see it in the dark. Strange.

MG: Does the success in the art market influence your work? I can imagine that there is a famous waiting list for your work.

MB: What am I supposed to do with that? There’s nothing I can do with that information, it is not going to influence what I do in the studio, one way or another. You have to have good dealers whom you trust.

MG: How do you feel when you see your painting at an auction?

MB: I hate it, who wouldn’t? It’s like your love-letters that you wrote to somebody would be on the auction block, it is so personal and so private. I don’t mind that people sell my work. You do what you need to do but I hate the publicness of an auction. I wish the seller would do it through the gallery. And that is mainly the way that has been done a lot, just, through the gallery; this is respectful of the work and of the relationship. I always find it a bit funny, the auction house respects the person that is selling it, but the artist is on the block, we have no privacy. So selling at auction always makes me really uncomfortable; not because they are selling the work, but because it’s so public.

MG: So do you have a conflict with the collectors who are selling your work in this way?

MB: No, I don’t have any problems… it’s just uncomfortable. Works are like relationships; they are super private. We black people have the saying: putting your business on the streets. Nobody wants to have his business out on the street. Like when you are having a bad time in a relationship, not everyone needs to know. And that is how it feels like, you flip through the catalogue and there you are.

MG: Do you have personal contact with the collectors?

MB: Not too many but I do know some. Over the years you get to know a few.

MG: If you speak with the collectors, do you feel they treat you like a trophy because you are producing these great works of art? Do you just think there’s the possibility of having a normal relationship with the buyers of your works?

MB: I think the possibility of having a normal relationship is there because I treat everybody the same. I really do. As a rule I don’t accept the hierarchy in the art world. I come from a service background. I worked in my mom’s hairdressing salon when I was eleven, I was the little boy that put you under the dryer and go to the store and buy you a soda. So I am very used to sort of treating people kind and respectful, all people, so I think that this part I have carried with me. If someone whispers in my ear that is this person is this or that, I don’t care. If they are an asshole, they are an asshole; if they are decent, they are decent. It’s much easier to just treat everybody decent.

MG: Do you think that the fact that you are this tall African-American and gay help create a kind of myth around your person that also contributes to your success as an artist?

MB: I don’t know. I am sure all those parts make up me. So if I wasn’t me, I guess I wouldn’t be who I am.

MG: You have been living in Los Angeles your whole life more or less. How is Los Angeles now? Is it becoming a more artistic city?

MB: I like it because the paintings dry pretty quickly. I can pull my paintings out into the sun and they dry really fast, it’s true.

MG: That’s the mystery of LA.

MB: It takes forever to dry in other parts of the world. I think it’s the last frontier. LA has the history of no history. No matter how serious the city wants to take itself, it is really young. The city is so young that it can’t help to be just a little bit tacky, just a little bit vulgar. Which I kind of like. I think there is a lot of space in LA. You can live here in your studio and be completely isolated and do your work, or you can go out and see people. It doesn’t have a center, a real center. It’s almost like one big abstract painting.

MG: Is the abstract quality of LA what connects the city with your art?

MB: My mother always showed me things that I would draw, and I would always draw abstract, even at school when drawing a pony, the pony was always abstract. I never got this figurative moment. LA is in a way like my paintings: people would stand in front of my painting and they would say: I think that this is Cairo and I see a face there. And I look and I would say, I don’t see any of that. So I think that’s kind of LA, people always try to find the face and the fork and the pony. But they are not there, there is no center, and you have to be just okay with that.