Boris Mikhailov

Published: January, 2012, Zoo Magazine / Made in Mind

Boris Mikhailov is one of the leading and most celebrated artists to have emerged from the former Soviet Union. Through his rebellious nudes and formally and ideologically disturbing photo series, the Ukrainian photographer has observed and analyzed the political and social mechanisms of Soviet society from the inside. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, he shocked the world with his photo series Case History, in which he mercilessly showed the invisible tragic spectrum of post-Soviet society and its individual victims.

Marta Gnyp: Lets start from the very beginning. You got interested in photography while you were working as a young engineer in Kharkov in the Ukraine, at that time one of the republics of the Soviet Union. Where did you work?

Boris Mikhailov: I started to work for a military factory that produced equipment and machinery for the space technology industry. At that time I didn’t understand quite well what the factory was doing. It was a closed enterprise and specially monitored. Already then, I was attracted more by art than by anything else.

MG: Did you get a chance to get into contact with something more artistic?

BM: I was encouraged to make a film about the factory. It happened that that place was connected to [Ukrainian and Soviet educator and writer] Anton Makarenko. In the 1920s, he collected homeless children and set up a labor colony in Kharkov where the FED camera was produced. All this happened in and around the factory. While making this film, I understood that I couldn’t show this material to anybody, because it was not in accordance to the Soviet propaganda. And then by coincidence, I got involved in photography. I was 28-years-old when I took my first photo, and it felt good. This was a picture of a girl on the street with a cigarette in her mouth. At that time the girls were not smoking on the street, it was not done. I was amazed. I was attracted by this other, not official, reality.

MG: You have never had any photographic education?

BG: Nothing. And then I started to take different kind of photos; the naked body fascinated me.

MG: Was the nudity a taboo?

BG: Absolutely. In the Soviet time, there were no nudes, naked bodies were never shown, the nudity simply didn’t exist. There was no pornography.

MG: So you didn’t have any material to relate to?

BM: Sometimes we got Czechoslovakian and German magazines with some naked pictures. But in general, there was nothing so I started to take the pictures myself. We had a group of a few people doing it.

MG: At that moment you were still working officially at the enterprise.

BG: Yes, but quickly after I became a victim of a provocation—first in the factory laboratory and then at home. KGB searched through my flat and found photographs with half-naked women: you could see a bit of the back, a bit of something else, and I was fired from the factory in a very shameful way. They spread bad rumors about the women I photographed. Shortly speaking, I was out, dismissed, fired.

MG: What was the reason for the provocation?

BM: One man wanted to get rid of me, but it is a long old story. When I tried to defend my right to make nudes they said, `you don’t have any rights.’ I said, ‘look there are naked photos in official magazines.’ They said, ‘you are allowed to look at them but you are not allowed to make them yourself.’ I stopped discussing it. After that incident, there was the Prague Spring and thereafter the situation even worsened. The Czech magazines were forbidden. I was under enormous pressure but I continued to take those photographs.

MG: You were permanently under control of the authorities?

BM: I showed these photographs in a club, where different people were coming, and which the KGB also infiltrated. Sometimes they asked me to come to them and interrogated me.

MG: It was only because of the nudes?

BM: At that time I was already doing ‘sandwiches’ (photographs that consist of several layers on top of each other). I found this new method. Since I have never learned the photography I didn’t have any holy respect attitude to the photography. So I took the film prints—they had just appeared on the market—and coincidentally they were put together on each other. I looked at that image against the light and then saw many different variants, wild possibilities of an image. And that was the moment that I decided to dedicate myself only to photography.

MG: Were you not scared that you would not earn any money?

BM: I could work as a ‘normal’ photographer with a dark room in Kharkov. I was printing different photos and in the meantime, was engaged with my own photography. There were no exhibitions, but I could show the photographs to my friends and their friends. At a certain moment, the series appeared; I travelled to Moscow and to Lithuania to show them to those who were interested.

MG: You mean your RED series?

BG: RED series and Black Archives.

MG: How were they received?

BM: It was stunning; they were completely new. A model for this kind of images has already existed since we are used to layered images in the movies— when one cadre replaces the other and we see the face of a woman and then a departing ship, flowing into each other. In photography, the dominant idea was that you should firstly conceive an idea of an image and then make it. It was such a stubborn concept that nobody thought about the other possibility. I didn’t want to think about the image first, but to coincidentally find it. This appeared to be much more creative than this constructed approach. There came several series for which I only collected elements, but the images connected themselves, so to speak— as if it were against the artistic consciousness.

MG: Did you consider yourself as an artist or a photographer?

BM: I’m a photographer and I like this practical approach. I need to see, and to be able to see, I need to take pictures of 1000 variants. To print 1000 variants would be very difficult, so this method was very fruitful.

MG: The series you made in this period were very interesting for you from the formal point of view; did you also consider this as a political or social critique?

BM: Absolutely. I did suffer under the Soviet system; I didn’t really want to fight but was fed up with the system. Everything was red, red and red. When I was taking pictures I was always scared. KGBvisited regularly my studio and searched through my photos. I felt threatened. Taking pictures was complicated; I was not allowed to photograph on the street. Only during the holidays I could relax a bit.

MG: How did you find other rebellious artists, the Moscow Conceptualists, or did they find you?

BM: I was always interested in sharing my photos with others, that is, when filmmakers came to Kharkov, I showed them my photographs. I showed even my photos to Andrei Tarkovski, who then replied, ‘I have no glasses with me, I can’t tell.’ But the cameraman with Tarkovski was amazed because he had never seen images like this. I felt myself like a rock star; people who saw my images were shocked in amazement and awe. Except the conceptualists, they had another approach. Through my photos I became known, and was invited for a show in Moscow.

MG: Was it an underground exhibition?

BM: In Moscow, these kinds of exhibitions were no longer underground. In Kharkov, yes. They invited a few Russian artists and myself. I put the photos from the Black Archive and Red Series on a table. And then Kabakov came to me and invited me to his studio. He sensed closeness in the attitude.

MG: The way in which you both react to your social and political environment?

BM: Exactly. How you react to the poor, red, ill, how you become aware of things in another conscious way. I got acquainted with him and other members of the group but Kharkov and Moscow stayed completely different. Each time I made a new series, I came to Moscow to show it. It was in the 70s. It was very important for me to understand how others were thinking about the world. The people who influence you most are the people who are close to you, not the ones far away. These close people were till that moment the people from the photography field, so this is why I was relating mostly to the photography. But once my close friends appeared to be artists, I started to think differently.

MG: What has changed in your approach?

BM: I saw my photos as a development of the photography. I started to consider the sandwiches like new possibilities of the photography because they were analytical from inside. Although they were made pure in a photographic way, coincidentally and at random, which is not typical for the artistic process. The artists think they are very smart.

MG: How was the relationship between art and photography at that time?

BM: The artists were very important and photo-graphy only started to play a role. The artists had more power, formed a bigger group and they were intelligent; they were ahead of photography. Only later in the 90s did they lose their social position. Then photography appeared more suitable to catch the moment. The artists were very important for the Soviet time, but when the Perestroika started, they didn’t digest it as properly as photography.

MG: Why did photography become so important? Because it was quick enough to react to many historically-loaded changes in Europe? After the fall of the Soviet Union, nobody has had a ready program, not just artists.

BM: Their reaction to what was happening was blocked. There were some actions and new works, but generally speaking, they continued the line of irony. I was especially interested in the illness. I wanted to show the tragedy. So art was irony and this was time to quit it; the irony was over and passé.

MG: You found your way into the tragedy and then you made your famous series Case History.’

BG: It resulted in more series: At The Ground, Blue Series and Case History, At the Dawn.

MG: Most articles state that in these series you photographed people who couldn’t find their place in society after the Soviet system collapsed. The Soviet Union must have its homeless, drug-addicted and social outsiders as well. They had to be visible somehow.

BM: There are a few opinions on this subject. One is that this group had always been a part of society. I saw bums, homeless alcoholics, only once during the Soviet time when I was in Kamchatka. What was well known was the notion of parasite, scrounger. Those people were forced by the militia to work, not in the prison, just to work and to sleep in the public almshouses. They were not visible on the street. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, all of the sudden there was no work, no social control system, so they crawled into the streets. Alcoholics, people who came free from the prison, or normal people who were not able to pay for their flats any longer. They formed a new class, a phenomenon that I didn’t understand at first. It took me a long time to become aware that there was a new big social group in society.

MG: How did you get in touch with them? Looking at the pictures, they were at ease with you.

BM: In the beginning, they opened themselves more to my wife than to me.

MG: Did she assist you in the series?

BM: Actually we did the series together. We have been working together for a long time already. She is also an engineer and photographer.

MG: So how did you approach the vagrants?

BM: It was very difficult for me because I didn’t have any method. I have never asked people to photograph them; it’s been always natural. But at that very moment, I sensed a pos-sibility to understand some important processes, comparable to the processes in the USA during the Great Depression. The American government at that time sent photographers to document what was going on. I thought about myself in that way.

MG: In the footsteps of Walker Evans?

BM: Yes, I had the feeling that fate has given me the task to do it. The method here was different, however. I needed to pay those people to be able to photograph them.

MG: How much did you pay them?

BM: Small amounts of cash. There was nothing extraordinary we asked them. I didn’t have the feeling that I was humiliating them. It was their natural environment; for them to show their naked body was not a big thing.

MG: Why did you ask them to show their bodies?

BM: Why is the nakedness of ‘normal’ people acceptable and theirs is not? There were also other reasons. I was curious—are they really starving? If so, they should be skinny, but they were not. So they have something to eat; so our judgment on them is not right. In this way I was doing my research. Of course, I’ve been always fascinated by the naked body in general. Without this forbidden fascination I wouldn’t be able to do it.

MG: I was also thinking that if a badly kept homeless alcoholic woman is displaying her naked body it makes her a woman again.

BG: Exactly. They are showing that they are women and at the same time how they can survive. How could I show that their bodies are their income source? It is not so easy to present their way of living and understand their life.

MG: Did you stay in contact with them? They didn’t want to see the pictures afterwards?

BM: How? Give them my business cards? They live on the street, today in one shirt, tomorrow in another.

MG: Did they enjoy being photographed?

BM: They appreciated that someone noticed them. In society, they are untouchables, comparable to the untouchable caste in India. There is a moment that you can speak of abuse, but you can speak of abuse in every human relationship. The lawyer is abusing his client as well; the doctor does it since he gets money for advice.

MG: How did it work out in practice? You or your wife went to them and asked ‘may I take a picture of you?’

BM: The beginning was very difficult. As I said before, I have never given to people I photographed any money. But if you want something from a bum, while he is asking you for money, you have to give. Once it happened, you understand that this is the right working method. Then there was an individual approach. Vita approached one man, for example, and told him, ‘we like your face.’ He asked, ‘am I so awful?’ She said, ‘no, you have a very strong face.’ And then he agreed. Then we asked some other people who knew other bums.

Vita Mikhailov (his wife, who just joined us): There was another thing as well: to make a series you need to take thousands of photos so it means you need to develop relationships. This is why you need to give the confidence of your intentions and attitude toward them. So when I was talking on the street with my ‘normal’ friends, and a bum came to me to ask something, I treated him as a completely normal person. I shook his hands and talked to him while standing together with my friends. You crossed the line so you mustn’t be ashamed of being a part of their lives. You don’t speak with them in secret but you show to the world that they are part of your life as well. Although you don’t know whether the series will ever materialize.

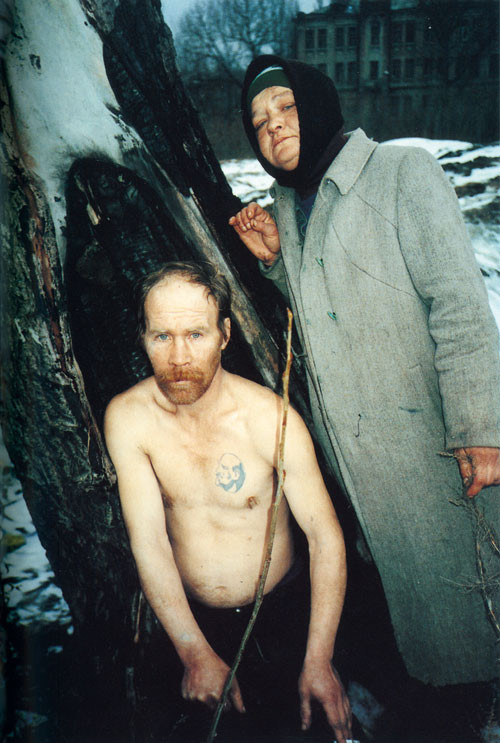

MG: Why did you choose this photograph (one from Case History) to hang in your living room?

VM: For me, on the one side we got closer to this woman and man: we met them several times, kept in touch for a longer period of time; we were involved in their personal stories and complaints. On the other side, they represent the unity of two symbols: one Russian and one Soviet brought together: the woman looks like the classic Russian babushka, the man has a tattoo of Lenin on his shoulder and looks like Lenin himself.

MG: Then Case History became a great hit in the West?

BM: It is well known and appreciated now, but it came into the West very calmly. I think that the size of the print was extremely important. The subject without this huge format would not work. The size was for me connected with the feeling of the sadness and suffering of the country. And the suffering shouldn’t be shown in a small format.

MG: You often showed couples together. Did you want to show that they experience normal human feelings too? For example, with the Wedding?

BM: In Wedding, there is another issue. The once stable middle class has also experienced transformations. You have bums, but there are also people who are not far away from this border, but not there yet, not far in the moral or visual sense. These couples you could place in the bum category or at the lower middle class border. For me, it is easier to categorize with whom I am working. Then I can give all my attention to some points. Firstly, there was the moment to give attention to the tragedy, then it passed and you should look for the new.

MG: What is changing, what are the new dangers?

BM: The new dangers of today are not clear to me. Perhaps the next variant is not to find a new danger: there is a part that has been researched but the other not. What is the other part? Can I see it and touch it? The second part in the previous projects was for me the image of the people who were sitting at the bus stops. The streets with specific character, the rhythm of the individual place, not the rhythm that is common in New York and Kharkov. Now is the time that the West entered into the Ukraine. From the photographic point of view, the place became different. Less aggressive, less active, less specific. You see the advertisement, the clothes are sometimes the same as here. I am not that interested in this image. From the other side, I don’t think you should look for something else.

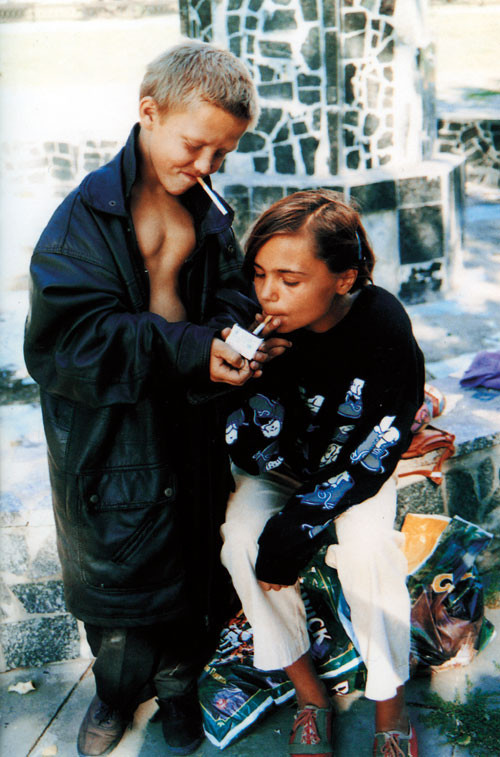

MG: Did you ever experience such a feeling of compassion for the people you photographed that you could not work? I mean, the poverty or the critical situation of the people such as the young children in Case History who sniffed glue?

BM: As photographer, I need to find something. The illness, something worth remembering as part of the history of the country. I didn’t understand what the children were doing until I saw the situation on the photo; we were sitting, talking, as if everything was normal but in the meantime they were sniffing glue. Only in the photo did I see something I have never seen in life. There are moments that photography discloses more than you can see. Photography can force you to a deep understanding. It gives you the surprise.

MG: Who found you in the West?

BM: The first book with my photographs was made by Ms. Mrazkova from Czechoslovakia. We were afraid of what would happen if the Soviet authorities discovered it. My wife constructed stories of what we would say if the Soviets were to ask us how my photos found their way to this publication. Mind you, there was nothing exceptional there. After this publication, nothing happened. Then the Finnish saw me in Moscow, made a book on Soviet photography, and in the 90s, the exhibitions started.

MG: When did you start to work with Western galleries?

BM: First one was in France, but it was not quite clear what they wanted. Everything was very slow and quiet. Very few sales. But I didn’t need a lot. For 10 dollars, I could feed half of Kharkov, so we did. We got 100 dollars and could live a couple of months on this money. We didn’t get much at that time. Then came more exhibitions, more galleries, I sold more.

MG: When did you decide to move to Berlin?

BM: Long ago, but it didn’t happen so quickly. I was invited for the DAAD program in Berlin for one year. During that year, I made friends here, became acquainted, and found myself more ready for this place although I don’t speak German at all and not good enough English. But I have found people with whom I can meet and communicate.

MG: Do you intend to learn German?

BM: I would love to but it is a bit too late for me. When I try to learn new English words I am falling asleep and cannot remember them the next day. There are moments in life when it is too late to learn something. I regret it because living in a country and not speaking the language blocks you from accessing the culture of which I would like to know more. This is important to understand what is going on.

MG: On the other hand, you have a different perspective without being in the middle of the language; your observations are different.

BM: That’s true, you start to look more active; you interpret all you see in your way.

MG: How is the reception of your works in Russia and the Ukraine? Are there many collectors there collecting your works?

BM: No. In the Ukraine, you have the very good collection of Pinchuk. That’s all. In the West there are many collectors of my works in many countries, even in Australia and Japan.

MG: How do you explain why the Russians are not so interested in your work?

BM: Firstly, they don’t pay attention to the fact that you were the first who developed something. Secondly, the concept ‘you don’t wash your dirty linen in public’ is very dominant. People think, it is our mess; you shouldn’t show it to the outside world, especially with regard to bums.

MG: Because they show a specific group that undermined the whole idea of the healthy society?

BM: It reflects something that you should not show; it is morally unjustified to touch this subject. If you don’t touch it everything is okay. If you want, you wouldn’t see anything. You turn your back and you just don’t see anything. I understand that there is something uneasy about those photographs. But you learn how to treat the subject, you start to take pictures, and you would get something. It is a profession.

MG: Did you ever think about photographing the new rich?

BM: I did. There was a moment that you could do it, when this process only started. But at that moment, I was here in Berlin. I’m glad I didn’t do it because now it would be impossible to show these pictures. They would kill me. One foreign girl did a good series, she approached every one of them, and she made them relax. She put them in a bath. Everybody has his or her own specialty.

MG: The last question considers your body. I saw your series, ‘I am not I’ in which you photographed yourself. Do you like to take pictures of yourself?

BM: No, I don’t.

MG: So why do you do it?

BM: Usually artists don’t show their bodies. I haven’t seen this ironic or mocking self-portrait of the artist in Russia before I started my self-portraits. I thought, if you criticize someone, start with yourself. When I got involved in photography, I decided to photograph myself as well. All of a sudden, you see a face that is different from a face that you see every day. This is not you. This is a face. Moreover, when I first took photos of myself, I saw a face that was different than the one known from the ideology of the Russian man. This man was an intelligentik (an intellectual, not a worker, who is not to be trusted in the Soviet Union). But this intelligentik should have been also presented to the public. I am photographing the others, but who am I?